These days ambitious NZ politicians are more likely to be crafting a Facebook post than a memoir. Danyl Mclauchlan gets absorbed in the towering 1974 book by the man who would become the most powerful PM in modern NZ history.

“When I was five I tore a cheek muscle in a fall and acquired a facial defect which appears when I smile and which my friends call my dimple and my foes a scar or smirk”

They used to write books. I found this one up at a second-hand bookstore, sitting on the shelf alongside Geoffrey Palmer’s Unbridled Power, Michael Laws’ The Demon Profession, Roger Douglas’s There Has To Be A Better Way; Marilyn Waring’s If Women Counted (easily the most influential book published by a New Zealand member of parliament). No books by any recent politicians, though. Now they update their Facebook profiles, and most have staff to do that for them. Politics has changed but stayed the same, I thought, flipping through Muldoon’s book, and I was curious about how and why. So I bought it and read it.

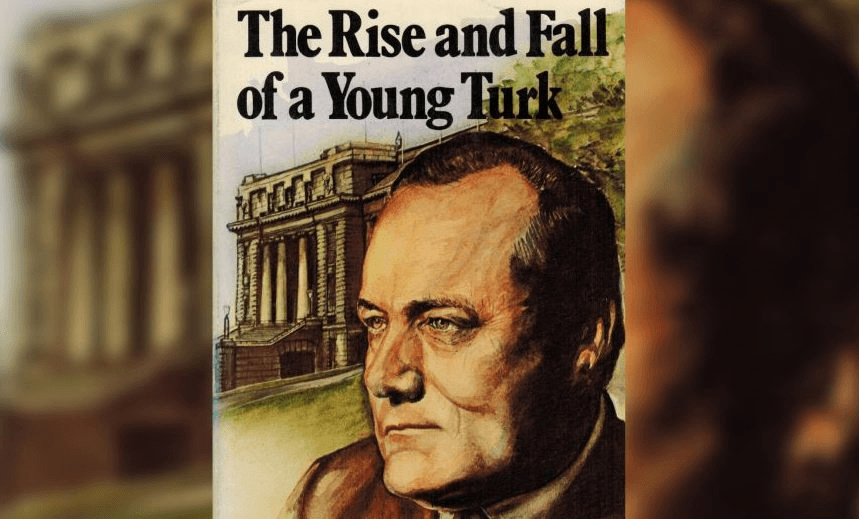

This was Muldoon’s first memoir, published in July of 1974, the day after he became opposition leader. He went on to write three more: his biographer, Barry Gustafson was not impressed with these subsequent efforts – “boring, superficial narratives and self-serving opinions” – and they sold poorly. But Rise and Fall of a Young Turk was a huge success, eventually selling over 32,000 copies. Eighteen months after it was published Muldoon was prime minister.

Apparently he wrote it himself, and it accomplishes the trick of being a highly artificial piece of political messaging which feels completely authentic. Muldoon’s dry, amused croak is in every line. Gustafson reports that he wrote the book quickly: I suspect it is an aggregation of speeches, anecdotes and jokes built up and polished over decades of political life, packaged together to sell the author as prime-minister-in-waiting.

The way he goes about this is quite clever. The first chapter of a memoir or biography is usually dull: ancestry; family; childhood: “the David Copperfield crap” that no one really cares about. Muldoon solves this problem on page one, second paragraph when he compares his Irish ancestors favourably to a “red guard” of contemporary Irishmen who, he claims, were infiltrating the New Zealand union movement to cause “nothing but harm to New Zealand”. And with that he’s off, passing the stages of his age and youth and linking them to then contemporary political issues, using them as pretexts to promote himself and attack his many enemies.

These are, in rough order of existential threat: communism; the union movement; foolish young radicals (especially those deluded into protesting against nuclear weapons, apartheid South Africa, the destruction of Lake Manapouri to build a hydroelectric dam, or a state visit by Muldoon’s good friend President Suharto of Indonesia); and finally, the deceitful, arrogant, incompetent third Labour government, who know nothing about economics and are wrecking the country.

We learn that Muldoon was a quiet kid. Father with health problems who was hospitalised for most of his son’s life. Raised by his Mum and staunchly socialist Grandmother. Brilliant at school. No money for university. He studied accounting by correspondence and then went to war. New Caledonia. Egypt. Italy. His Battalion helped capture Trieste. Muldoon is self-deprecating about his war record: “The order to advance was given. The man next to me went forward, looked around, saw me lying in the furrow and came back thinking, no doubt, that I had been hit. To his disgust I was fast asleep.”

He hits the same tone when talking about his early years on the campaign trail: “At another house I pressed the bell, stepped back and felt something tip over. Quick as a flash I turned and by a miracle caught it before it hit the ground. As the lady opened the door there I was with a potted cactus in my hand – wrong side up. As we extracted the spines together I think I got a vote at that house.”

The book builds a credible yet flattering picture of the author, story by story, joke by joke, page by meticulous page: it’s like watching a line of factory robots assemble and colour a car. We start with a decent bloke; funny, hard-working, religious but not mystical; pragmatic; very clever but forcefully anti-intellectual. He won the marginal seat of Tamaki in the 1960 election which saw the National government of Keith Holyoake elected to power, where it would remain for 12 years. The intake of new National MPs was mostly young, mostly war veterans: the press gallery dubbed them “the Young Turks”.

Muldoon was under-secretary to the finance minister by 1963; finance minister from 1967 until 1972. Keith Holyoake was a formidable and ruthless politician, but in Muldoon’s version of events he plays a very peripheral role in his own government: a vague, benign presence, always referred to with deep respect, but always somewhere in the remote distance while his dynamic young finance minister runs the country and champions New Zealand on the world stage.

It has long been conventional wisdom in New Zealand politics (and it might even be true) that an international trip is worth a couple of points in the polls, especially if the PM can earn media by talking to the president of the US (this might not currently be true). The voters seem to like seeing our leader out there “punching above our weight”. So Muldoon describes every trip; every IMF conference or Commonwealth finance ministers’ meeting. He name-checks every luminary he ever sat next to at a state dinner. He devotes an entire chapter to assessing his “opposite numbers”, the treasurers, opposition leaders and heads of state of most of our allies and trading partners, reviewing them as if they were so many Bed and Breakfasts. Suharto gets the most glowing reference. He warmed to Lyndon Johnson but was not impressed with Richard Nixon – still the president when the book was published. The Foreign Ministry must have had a fit.

Later on, when he was joint prime minister and finance minister – a combination that made him the most powerful politician in our modern history – Muldoon would claim that he was the only person who understood the New Zealand economy. He doesn’t quite go that far here, but certainly he understands it better than those jokers in Norm Kirk’s Labour government. Look how economic conditions deteriorated as soon as he handed it over to them! Almost instantly! He’ll set things right. He’ll stand up for New Zealand and its decent hard-working people. He’s not racist but he’ll keep the Māori in line; perhaps, he muses, by banning violent Māori louts from the cities. The book builds, like a symphony, to a glorious movement not yet sounded, when destiny and the voters make him prime minister.

Plus ça change watch. Many elements of political life in the 1960s and 70s seem awfully familiar. When Labour caught Muldoon acting unethically he told the media that he was “relaxed” about it. Whenever Labour came up with a popular policy he stole it. Another biography of Muldoon published in 1978 by Spiro Zavos described him as a “politician who did not take risks and whose political philosophy was cautious and sterile … short term and reeking of expediency”, but Zavos also criticised the Labour Party for being obsessed with him, and having their hatred of Muldoon blind them to his effectiveness and popularity with ordinary New Zealanders, rendering them oblivious as to why voters sided with him over radicals and activists.

Muldoon describes MPs clashing like idiots in the House, especially during Question Time, and quotes extracts from Hansard in which National MPs call the Labour speaker “Hitler”, because he considers this such an amusing exchange. Francis Fukuyama has this theory that many of the components of contemporary democracy – debates, Question Time, other parliamentary rituals, election campaigns – aren’t about values or policy or getting good government. They’re about acknowledging that some humans have an innate need for power and conflict and domination, and the democratic process is a contained and non-violent way for them to act out these needs against each other in a way that doesn’t harm the rest of us. This makes me feel a little better about Question Time.

Things we should give Muldoon credit for: He introduced decimal currency (and there was a controversy about the designs of the new coins and notes, which he as an under-secretary handled with more skill and acumen than John Key managed with his flag debacle). He crossed the floor to vote alongside Labour to abolish the death penalty. He thought the European Union was going to be a disaster because you couldn’t have monetary union across so many disparate economies. He visited the United States in the mid-1960s, at the height of the Imperial Presidency and the Great Society and declared that it was a corrupt, broken, decaying system unable to cope with modernity. He was a staunch supporter of New Zealand’s then comprehensive Social Welfare system, and saw dignity as an integral component of that system.

He grasped the power and opportunity of television earlier than most. It’s hard to imagine Muldoon reading McLuhan’s Understanding Media, but maybe he did: “My first experiences in 1964 and 1965 came when current affairs television was feeling its way. I realised it was a different and an intimate medium in which you are speaking to people individually in their homes, and where every gesture is magnified as your head, and from time to time part of your body appear in the centre of the box. You can leave a good impression on television and leave no lasting thought. A politician must seek to leave a thought, and one per appearance is about the maximum possible, maybe on rare appearances two. This means that the spoken word must make more impact than the sound or appearance.”

Hard to improve on that advice today. John Key (or at least his staff) was good at crafting lines to impact the viewer. Winston Peters is a natural. None of the others seem to bother.

He tells a good story, and it no longer matters whether many of them are true: he claims that his Labour opponent in Tamaki in the 1966 election was “the toughest campaigner I have ever opposed”, due to the fact that he had “several almost identical brothers including a twin, and the amount of canvassing they did was phenomenal. No one knew which was the candidate and he was reported as being in different parts of the electorate at the same time.”

He was a rabid anti-communist: his hatred of socialism is a constant theme, although when he becomes Holyoake’s finance minister these attacks on the delusional madness of the socialist system are often interrupted by detailed explanations of policy initiatives like the National Development Conference: “A major and comprehensive exercise in indicative planning covering the whole economy” to be achieved via “10-year plans”. We hear about his very frequent mini-budgets: just before Christmas of 1969 he “increased sales taxes on clocks, watches, firearms, photographic requisites and gear, and hire purchase terms.” He gloats about the voter backlash being forgotten over the holidays.

Muldoon doesn’t believe in ideology. He’s a pragmatic man who believes in “whatever works,” which perhaps explains why, once elected prime minister he was able to turn New Zealand into the Albania of the South Pacific while warning everyone to guard against the red menace. Keynes said, famously: “Practical men who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.” Neoliberal economists would later charge that the scribbler Muldoon distilled in his frenzies was Keynes himself.

He talks candidly about the tensions in Cabinet. There was always trouble between the minister of finance and the minister of labour. The labour minister wanted wage increases because if workers didn’t get them there’d be industrial action and that minister would be held responsible. But if they did get them it would lead to further inflation, and it’d be the finance minister’s head on the block. Muldoon keeps himself busy fighting inflation by taxing everything so much no one could buy much of anything, even if they did get a wage rise. Sales tax on motor vehicles hit 40% under his watch. Yet by 1969 inflation was at 10%. Nowadays the Reserve Bank would just increase interest rates, sucking money out of the economy by increasing the cost of borrowing and rewarding those who save. “I was never convinced of the efficacy of interest rates as an economic regulator,” Muldoon sniffs.

The price of wool, then our major export commodity, is often mentioned. Whenever the export value declines he borrows money from the British government or the International Monetary Fund so that the government can buy it off the farmers at a suitably high price to keep the regional economies healthy (and voting National). Then he chuckles about the idiocy of the bureaucrats and socialists who wanted him to devalue the currency, which was simply set by the Finance Minister after negotiations with the rest of Cabinet (at least until the 1970s when it was pegged to the US dollar) to make it cheaper for export markets to buy from us.

A character in a Hemingway novel famously described himself as going bankrupt “Gradually then suddenly.” The spectre of “suddenly” looms over all Muldoon’s economic pontifications, frequent mini-budgets, wage and price freezes and import controls, and it acquires a grinning face near the end of the book when newly elected Labour MP Roger Douglas appears as a minor character. As opposition leader Muldoon railed against the third Labour government’s compulsory superannuation savings accounts: during the 1975 election he told the voters it was communism (hence the infamous Dancing Cossacks ad) and they believed him. If we think politics is stupid today, it’s only because we forget how intensely stupid it used to be.

And yet – it would be the height of contrarianism to write about the rise of Robert Muldoon, one of the darkest characters in our political history, and wax nostalgic about how those were the good old days. But you can’t help contrast this cunning and funny book with the way modern politicians court the public: by running to the women’s magazines, breakfast DJs and light entertainment shows to talk about their favourite food or dream holiday, or the special bond they have with their dog. They have to do that now: the world has changed; I get that. But I think we can feel sentiment for this old monster’s book, if not for the monster itself.

This content is brought to you by LifeDirect by Trade Me, where you’ll find all the top NZ insurers so you can compare deals and buy insurance then and there. You’ll also get 20% cashback when you take a life insurance policy out, so you can spend more time enjoying life and less time worrying about the things that can get in the way.

This election year, support The Spinoff Politics by using LifeDirect for your insurance. See lifedirect.co.nz/life-insurance