The NZ election campaign coincides with a crunch time for the future of the Trans Pacific Partnership. In the absence of the US, attempts to renegotiate an 11-member TPP risk scuppering a deal that could bring enormous benefits to New Zealand, argues Stephen Jacobi, executive director of the NZ International Business Forum.

Good ideas never die and so it has proved with TPP. No amount of huffing and puffing from the arch-protectionists and the anti-globalists, not even the president of the United States, has (yet) been able to consign TPP to history. Those people with genuinely held concerns about aspects of the agreement – and there are many – might wonder why this is so. It’s because the remaining 11 parties to the agreement continue to see it as a means of accelerating trade and investment growth and providing a new benchmark for improving the rules against which business is done in the region. The parties are convinced that the agreement, as negotiated, contains the necessary safeguards to protect domestic sovereignty and the continuing rights of governments to regulate in the national interest.

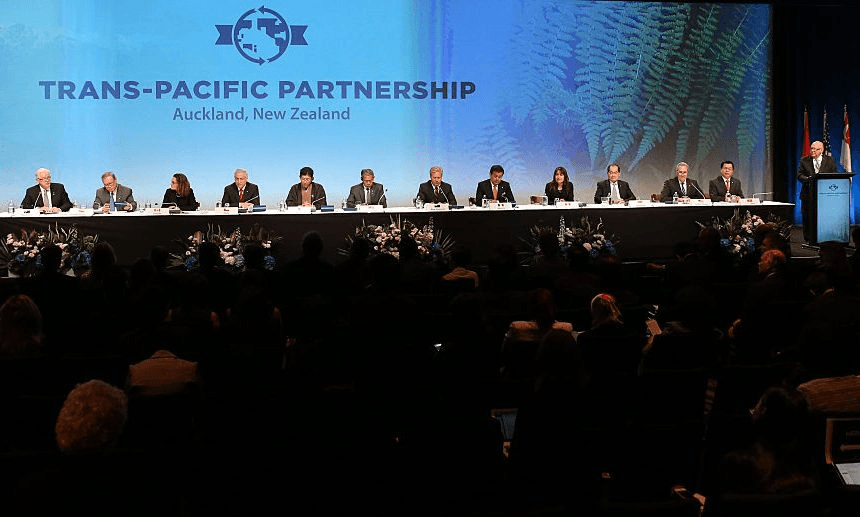

Officials are meeting again in Sydney this week to try to hammer out a recommendation for TPP leaders to consider when they gather for the APEC Economic Summit in Danang, Viet Nam in November. Officials have met on two earlier occasions since the United States withdrew from the agreement. Reports suggest the coalition is holding at least for the meantime. At issue now is the extent to which the agreement, signed in Auckland in February 2016, and ratified by both Japan and New Zealand, should be amended other than simply the clause by which it enters into force. The latter clearly needs to be changed, but is that all?

It would seem logical to strip the agreement of those particular US demands in intellectual property, medicines and state owned enterprises, but there are good arguments to the contrary. Some TPP members hope that the United States will change its mind on TPP and return to the fold. While this is out of the question for the current administration, things may change in the future. It might also be possible to leave these elements in the agreement as is, but agree not to apply them before the US joins. That would preserve a strong enticement.

Beyond this, there is a risk that if the agreement is opened up for substantive renegotiation, other parties might find the excuse to relitigate elements which they found problematic. It’s no secret that everyone in TPP found something to be unhappy with – even New Zealand was disappointed with the outcome on dairy. Reopening the negotiation could risk further unravelling the delicate consensus and require years to rebuild. This risk has led both Japanese and New Zealand governments to call for the agreement to be ratified as currently concluded.

For the business community, which has waited eight years so far for TPP, the prospect of going back to the drawing board simply risks delaying the introduction of much-needed improvements to the way trade and investment is governed and regulated. Years’ more wrangling about TPP is not attractive. Business models are changing rapidly and TPP runs the risk of being outdated the moment it takes effect.

New Zealand exporters to Japan have particular cause to worry. TPP would have delivered the free trade agreement with Japan that New Zealand has been seeking for some years now. Japan is the only country in East Asia where we do not have an FTA. Already our competitors in Chile and Australia have freer trade than we do. Now, the European Union and Japan have concluded a political agreement on a new FTA. Without TPP New Zealand exporters of beef, dairy, horticulture and wine face an uphill battle in Japan. The problem is particularly acute in beef, a trade worth around $150 million each year. New Zealand exporters pay 38.5% in tariffs whereas Australian competitors pay only 27.2%. A new safeguard tariff introduced recently does not apply to Australia and means our tariff goes up to 50%.

The importance of the Japanese market is what leads a delegation of New Zealand business leaders from the NZ International Business Forum to visit Tokyo next week. They are keen to hear from Japanese business organisations and academics about how they see the challenge of salvaging TPP and to encourage them to express support for the earliest possible entry into force. Japan’s leadership of TPP-11 is very welcome – it arises from the importance the government of Shinzo Abe attaches to the structural reform of the Japanese economy which is emerging from decades of lethargy. Agricultural reform is a particular priority and something New Zealand can potentially help with given our own experience in removing subsidies and integrating our export companies in global markets.

For the longest time, New Zealand exporters have operated with the bipartisan political support from major political parties. In recent years, during the long and controversial negotiation of TPP, that bipartisan support has broken down, much to the disappointment of the business community. In the current electoral campaign, there is disagreement about whether to support the concept of TPP-11. The National-led government is a strong supporter, the Greens and NZ First are opposed and Labour believes TPP needs to be renegotiated to take account of its proposed policy to ban purchases of residential property to overseas tax residents.

It is not unusual for an incoming government to seek to re-evaluate trade policy. Governments make decisions differently from Opposition parties. Governments have access to the free and frank advice of officials and to representations from the business community and other stakeholders. They have to take account of the full range of issues, including, in this case, the serious damage which would be done to New Zealand economic interests in Japan if TPP does not proceed. This calls for governments-in-waiting to exercise caution in signalling future trade policy changes. In the case of TPP it might prove possible to address residual concerns about aspects of the agreement from within the agreement itself, rather than seeking a re-negotiation.

In coming weeks, we will hear much from our political leaders about having to make tough decisions. TPP could be one of these. Whoever sits down with the other TPP leaders in Danang will have a big call to make. The opportunity to secure New Zealand interests in Japan and other markets make it imperative that TPP does not get “lost in translation” in the midst of negotiations that are now under way and a rigorous election debate.

This content is entirely funded by Simplicity, New Zealand’s only non-profit fund manager, dedicated to making Kiwis wealthier in retirement. Its fees are the lowest on the market and it is 100% online, ethically invested, and fully transparent. Simplicity also donates 15% of management revenue to charity. So far, Simplicity is saving its 7,500 members $2 million annually. Switching takes two minutes.

The views and opinions expressed above do not reflect those of Simplicity and should not be construed as an endorsement.