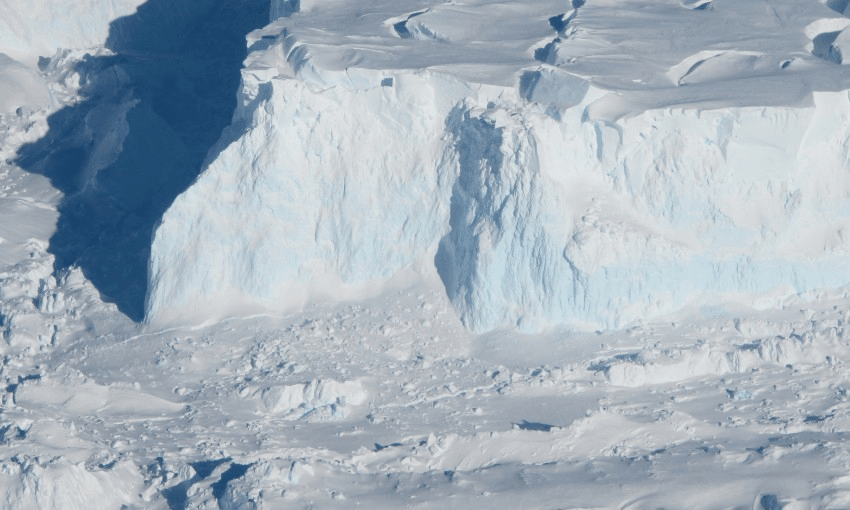

The loss of Antarctic ice sheets will likely cause a sea-level rise of 20 metres in coming centuries, a Victoria University-led study says.

The earth is heating up and the planet has been here before. A new study into the mid-Pliocene’s climate reveals how today’s polar ice sheets may respond to climate rises expected this century.

More than three million years ago, in the mid-Pliocene era, the planet’s mean surface temperature was between 2°C and 3.5°C higher than pre-industrial levels while the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration was about 400 parts per million – a figure we have already surpassed as greenhouse gas emissions continue rising.

A study by Victoria University of Wellington’s PhD graduate Dr Georgia Grant, has found that one third of Antarctica’s ice sheets melted during the Pliocene era, leading to a sea level rise of up to 25 metres above today’s level. It also found that the era experienced regular sea level fluctuations between 5 and 25 meters, with an average of 13 metres.

As part of the study, Dr Grant developed a new method of determining sea-level change by analysing the size of particles moved by the waves.

Because of the way waves interact with the seabed, grains of sand are coarser closer to the shoreline and finer deeper into the ocean. The coarser sediments need more energy to move, and the number of finer particles reduce offshore. Knowing just how much energy is required to move such grains and testing their size and amount in ancient sediment core allowed Dr Grant and her team to determine what the water depth must have been to have deposited them.

The method was applied to a geological archive for the Whanganui Basin, on the west coast of the North Island. Professor Tim Naish from Victoria University’s Antarctic Research Centre, who assisted on the study, says the basin provides solid evidence for global sea level change.

“It turns out, in our own backyard, we have the most detailed sedimentary record of global sea level change. It’s very unique, we don’t find that detail elsewhere and the reason is New Zealand sits on a tectonic plate boundary.”

He says the methodology can be recreated to study even older and warmer climates around the world, adding to the pool of knowledge on past sea-level fluctuations.

Apart from a few subtle differences in the geography of ice sheets, oceans and land masses, the similarity between the Pliocene’s climate and the changes expected this century mean the reaction of the polar ice caps back then could be what we are moving towards, 20-metre sea level rise and all.

Dr Grant says that though discovering such a rise was a bit nerve-wracking, it was not entirely surprising. It only confirmed what climate proxies have been expecting. “The marine base ice in Antarctica is highly vulnerable and can respond quickly in changes to warming. This is the first unequivocal evidence of what we always thought was going to happen.”

Last month, the IPCC released a report into the oceans and cryosphere (frozen parts of the earth’s surface), which found that the oceans and cryosphere had already begun absorbing the heat from climate change for decades.

The warmer ocean, paired with melting ice sheets and glaciers, are contributing to an accelerated rate of sea level rise. While the global sea level rose by around 15 cm in the 20th century, it is now rising twice as fast, at 3.6 mm per year. And it’s getting faster.

Even if greenhouse gasses are drastically reduced and warming curbed to below two degrees, by 2100 the sea will have risen by 30 – 60 cm.

Dr Grant says that finding a specific range of how ice sheets may respond reiterated the need to limit warming to two degrees above pre-industrial levels, but also reinforced the difference individual contributions can make, as well as well as what we can be changed with everybody working towards the same goal.

For Professor Naish, the study stresses the importance of keeping greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Climate Agreement.

“If we do not keep our greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Climate Agreement target of two degrees warming, then we may potentially lose not only the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, but also the vulnerable margins of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet.

“The point is that if we go back to the Pliocene, Antarctica looks very much like it did today. If you stay at two degrees for long enough, you will melt enough ice to raise the sea level by 25 metres. It will take thousands of years to get to 25 metres, but we’ve started that process with the warming we’ve already done.”

The study, which was funded by the Royal Society Te Apārangi’s Marsden Fund, also involved Dr Gavin Dunbar from the University’s Antarctic Research Centre, scientists from GNS Science, Waikato University, and scientists from the Netherlands, the United States and Chile.