An 1,800-page report, years in the making, has painted a profoundly stark picture for diversity. With up to a million species facing extinction, humanity itself is in peril, says the UN body that assesses the state of global ecosystems

A selection of expert views on the report, compiled by the NZ and UK Science Media Centres

Andrea Byrom: Nature is in peril, and humans are the cause

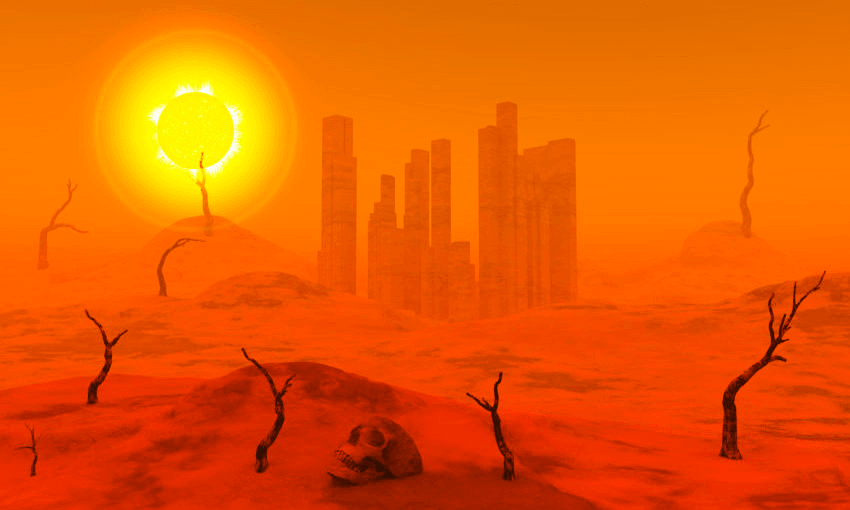

This report could not be more clear. Nature is in peril, and humans are the cause. Even more importantly however, it makes a very explicit link between biodiversity and ecosystem function: a loss of biodiversity – which has accelerated massively in the past three decades – is beginning to impact human development, economic productivity, security, and the societies we live in.

Put simply, we are making irrevocable changes to nature, and we need to take urgent action to prevent such changes before it is too late. In every domain, from the high mountaintops to the bottom of the oceans, from the Arctic to the tropics, in freshwaters and forests and oceans, human impacts are significant and wide-reaching.

The report is also crystal clear about the big drivers of global environmental change: (1) Changes in land and sea use; (2) Exploitation; (3) Climate change; (4) Pollution; and (5) Invasive alien species. These are prioritised in the above order, but it is acknowledged that different regions, and across different domains (for example freshwater compared with oceans), one or other of these drivers need to be afforded higher priority.

In Aotearoa, I suspect that invasive species are more front of mind for us than some other drivers (Predator-Free 2050 being the most well-known local example of the growing awareness of the plight of our biodiversity), but the take-home message is that together, these human-induced drivers of global environmental change need to be tackled head-on. It is heartening to see that significant attention was paid to traditional indigenous knowledge, and how indigenous peoples will be instrumental in co-developing solutions to our global environmental problems when so often in the past their voices have not been heard.

The report is a stark wake-up call to action, and to that end it provides tangible examples of action that can be taken now – particularly but not limited to policy and governance – that would make a real difference in reversing the decline. And most importantly in my view, it highlights that the global growth-at-all cost economic paradigm simply cannot continue without significant environmental impact. It identifies a need for fundamental, system-wide, and transformative action across technological, social, cultural, economic and environmental fronts, highlighting the sense of urgency needed to address the crisis at hand.

I’m in awe of the people that worked so hard over the course of last week to synthesise the huge amount of information available to them – and I’m in awe of the many scientists and researchers worldwide whose work provided so much solid background information for the report. Let’s just hope that the world is listening.

Dr Andrea Byrom is director of the NZ Biological Heritage National Science Challenge

Carolyn Lundquist: Amid the doom, there are seeds of hope

The report is the first global biodiversity assessment since 2005 and shows that species extinctions and habitat degradation are continuing. This report recognises it’s not just about how many species are going extinct, it’s also about the services nature provides for us, such as coastal protection and water filtration, as well the social and cultural relationships we have with nature, like the mana associated with abundant stocks of kaimoana.

It also shows amid the doom and gloom there are lots of seeds of hope. These are the many small-scale initiatives from community-led restoration programmes that are bringing nature back to cities, such as the many Hamilton gully restoration projects through to national commitments such as Predator Free NZ. These initiatives combined with new scenario modelling approaches are what we have to focus on if we are to bend the curve in the opposite direction.

Dr Carolyn Lundquist is principal scientist, marine ecology, NIWA and associate professor, University of Auckland

James Russell: No more time to debate or deny the science

The IPBES exists to normalise biodiversity in the same manner the more well-known IPCC has raised awareness about the impacts of climate change. Framing biodiversity as a collective good is challenging, as it has many facets and threats to it, which has made it difficult to conceptualise in its global totality.

The report paints a bleak picture of the current status of biodiversity and its decline over the past 50 years, but now makes clear that we can no longer say “we don’t have enough evidence”. The science is in and it’s no longer time to debate or deny the science, but to shift to discussions about appropriate policy responses.

In saying that, I found the framing of “opposition from vested interests” as problematic, as it creates an othering where there are sides of “good” and “bad” people. I think the reality is simply that we live in a world of self-interested people, where we all live in a dissonance where our actions and desires are at odds with what the planet can sustainability provide, especially when all of us desire these things. As it has been noted elsewhere, the key here would probably be to rein in the excesses of capitalism, one of the most egregious forms of resource hoarding. It has been noted that the fundamental tenet of economics is unlimited growth which is at odds with the fundamental tenet of ecology that is finite resources.

The emphasis on transformative change is important as it recognises we have to move beyond seeking technological fixes and look for meaningful behavioural changes at the personal and daily level. In particular the importance of acting locally to respond to the major threats in their local manifestations. I also want to emphasise how good the indigenous and local people section of the report is. Both Māori (indigenous) and Pākehā (local) fall within the scope of this section, and it empowers us all to think about how we can be more ‘indigenous’ in how we whakapapa (relate) to our lands and seas for their protection, and welcome new immigrants to our country to join our mahi (practices), regardless of our ethnicities.

I also found the focus on species extinctions interesting, as that captures only one extreme measure of biodiversity, but admittedly is one of the most powerful and worst, and also easily documented (ie the decline in natural areas). Islands differ from continents in their patterns of biodiversity loss and threats. Most extinctions have occurred on islands, and the major cause of these has been invasive species. Moving forward with the report’s recommendations we have to continue to pursue invasive species management in New Zealand, while not neglecting other biodiversity threats such as habitat loss and exploitation, and also preparing ourselves for the climate change threats which are still largely future forecast.

James Russell is an associate professor at the University of Auckland. He was an invited plenary speaker at the CNRS Dimensions of Biodiversity: scientific research to further the goals of IPBES conference in Paris the week prior to the IPBES plenary.

Alexandre Antonelli: Every extinction is a failure of humankind

In the same way that the IPCC Report on climate change has been mainstreamed, we hope that this IPBES Report can help do the same thing for biodiversity policy. Every extinction of a species is a failure of humankind. Even long before the last individual of a species dies out, in a zoo or botanical garden, it often becomes so rare to be ‘functionally’ extinct in nature. The loss of biodiversity is therefore a much bigger problem than just counting species disappearances: it is the loss of species in our garden, our city, our country.

This report’s message is therefore very clear – what we need now is massive, transformative and globally coordinated changes across all levels of society. It confirms that we can’t just preserve, we must reverse the trend by increasing biodiversity locally, regionally, and globally so I welcome the roadmap it sets out to address some of the challenges.

Despite the ambitious biodiversity goals that were set by the CBD – due to be met by next year – and the great efforts and good examples, this report shows that the overall outcome is an almost complete failure. We must learn from that process in order to not make the same mistakes. We just can’t miss this chance – lest it be our last.

Alexandre Antonelli is director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Helen Roy: A biosphere on its knees

The headline figures are bleak. The summary is essentially a statement of declines, some of which have been widely reported previously, such as global declines in pollinators, but others have received less attention, such as declines in soil organic carbon.

The proportion of land altered by human activities is now reported to be a staggering 75%. Similarly concerning figures are quoted for other ecosystems. Biological communities are becoming more similar over time and areas of high endemism, such as islands, are experiencing severe native biodiversity loss as a consequence of the adverse effects of invasive alien species.

The report succinctly refers to quantitative evidence where available but also transparently includes the sources of extrapolations where there are knowledge gaps. For example, when referring to insect declines, which have been the focus of much media attention over the last year, the summary provides a measured conclusion “Global trends in insect populations are not known but rapid declines have been well documented in some places.”

As the summary opens, and subsequently provides considerable evidence, “The biosphere, upon which humanity as a whole depends, is being altered to an unparalleled degree across all spatial scales.” It is clearly stated that “the goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories.”

Professor Helen Roy MBE is individual merit scientist, Centre for Ecology & Hydrology. She is IPBES lead author for European and Central Asia assessment

John Spicer: How do 7 billion human beings suddenly agree on an enlightened vision?

Reading the IPBES report there is a profound sense of déjà vu – in one way our general knowledge of biodiversity decline and what we can do about it seems to have changed little since the first global attempt to tackle biodiversity loss in Rio,1992. Many of the same points made here are found in the Convention for Biological Diversity, from 1992.

What has changed dramatically is the pace of change: biodiversity, and what biodiversity does to sustain every human being on our planet, is being degraded or destroyed faster than ever before. This is driven by the growing negative impact of the increasing scale of the human enterprise, what we do, and exacerbated by our inability or unwillingness to meet mitigating targets we set ourselves. These two points come out clearly in the report.

What also comes out is something that may surprise many. Of the prioritised list of proximate drivers of biodiversity decline, climate change is only number three. Climate change is certainly one of the greatest threats that face humankind in the near future – so what does that tell us about the first and second, changes in land/sea use, and direct exploitation? The current situation is desperate and has been for some time. In the context of our recent growing awareness (admittance?) of the dangers of climate change this report is a wake-up call to the even greater dangers of the way we alter and use biodiversity.

The report also acts as an interim assessment on our efforts to forestall biodiversity loss and promote sustainability through globally agreed goals. In this regard, it makes sobering reading. There is good news as the report highlights the “positive synergies between nature and goals on education, gender equality, reducing inequalities and promoting peace and justice.” However, this is set against the chilling statement that “current negative trends in biodiversity [loss] will undermine progress towards 80% of assessed targets of goals related to the sustainable development goals”. While this will affect all of us, the report leaves us in no doubt that, again, that it is the poor who do the suffering.

Finally in words reminiscent of the text of the 1992 Convention for biological diversity the current report emphasises that change aimed at halting or reversing biodiversity loss will only be effective if they are “transformative”. Numerous strategies are proposed, some old (not incentivising biodiversity destruction) and some new. But for me the key question remains how do 7 billion human beings suddenly agree on an enlightened vision of caring for biodiversity, and so care for our own future. The answer may well have its seeds in the movement which resulted in more than 1.4 million young people around the world taking part in school strikes for climate change – it’s not 1992, and there is a new generation now.

John Spicer is professor of marine zoology at the University of Plymouth

Richard Bardgett: Real change requires policies and incentives

The IPBES report makes it abundantly clear what will happen to the natural world if we continue as we are. This matters – not only for conserving the nature we see around us, but also for maintaining and increasing our own wellbeing and prosperity. Biodiversity and thriving ecosystems are critical for sustaining the natural resources on which our economy depends.

My own research in the relatively unexplored world of soil illustrates just how important biodiversity is. Food crops need fertile soils, and this is influenced by the vast variety of organisms that live in the soil. The diversity of plants above ground, and the birds and mammals that live off them, also rely on a healthy, biologically diverse soil. Science can help identify land management practices that sustain biodiversity for everyone’s benefit – but we will only see real change where the right government policies and economic incentives are in place to support it.

Professor Richard Bardgett is president of the British Ecological Society