May 20 – 26 is macular degeneration awareness week. The subject is a personal one for Grant Thompson and his daughter Donna, who have both been diagnosed the condition which can lead to blindness.

“I thought I just needed new glasses, but my optometrist told me I was going blind.”

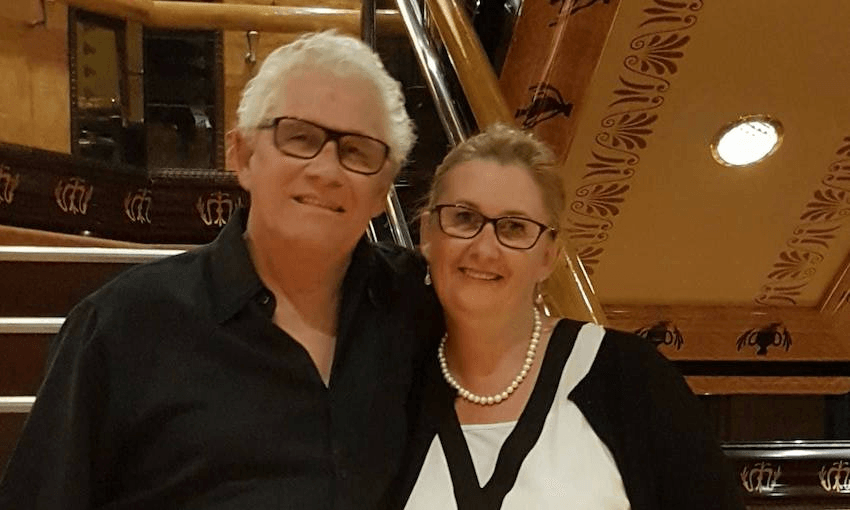

When Grant Thompson was diagnosed with macular degeneration eight years ago, it was a life changing event. The Napier-based dad of three had always been fit and well, and apart from being a bit short sighted, thought he was otherwise in good health. At 66, he was just settling into his retirement.

“I was very upset. I enjoy life so much, and here I was being told I would lose my central vision,” says Grant. “He told me it could be 15 years, or it could be less. No one knew. I was very depressed.”

Your macula is the photo-receptor rich membrane at the back of your eye that allows you to see sharp, central images. Macular degeneration can rob you of your central sight, leaving you just with blurred peripheral vision, or in some cases, nothing but a perception of light and dark. One in seven people over the age of 50 will suffer from it.

But it needn’t cause blindness. If diagnosed early enough, it can be treated.

“I’d never even heard of an Amsler grid,” says Grant, about the grid of horizontal and vertical lines used to monitor a person’s central visual field. He was given one to put on his fridge, and began using it weekly. “I think everyone over 50 should have one. Changes in the grid will let you know the early warning signs.”

Once a change in vision – often undetectable without the use of an Amsler grid – has been identified, you need to see a specialist immediately. They can begin a programme of treatment that can preserve your central vision – and in some cases even improve it.

“I had Drusen, an untreatable but mild form of MD, for two years before anything changed,” says Grant. “Then one day I noticed my left eye was bruised. I checked my Amsler grid and there was a change. I began Avastin injections the next day.”

Injections into your eye may not sound very pleasant, but for most of the 160,000-people living with MD, it’s the key to business as usual – without the injections, their vision would deteriorate in a matter of months.

“The injections are a happy day for me,” says Grant. “They don’t hurt, it doesn’t bother me at all. I had them every four weeks to start with, now it’s every six. Afterward I spend the afternoon to myself, relaxing, having a sleep. You know, life goes on.”

Grant admits that for the first few months after his diagnosis he was very depressed, but once he began researching MD, meeting other people living with it and finding support, he began to see that with treatment, it wasn’t as bit of a problem as he imagined.

“I’m still driving. I read more than I’ve ever read before. I play table tennis and tennis, walk and bike and do a lot of gardening,” says Grant. “I’m very active. There’s not a lot of difference between me now and me eight years ago.”

However, the one thing that bothered Grant was the genetic connection – he knew his three children would be more susceptible.

“I gave them all a lecture. I told them to use their Amsler chart,” says Grant. “But they were all so young, I didn’t think we needed to worry too much.”

Then one day, two years ago, Grant’s daughter Donna popped round. As usual, he got her to look at the Amsler grid on the fridge.

“The lines weren’t straight,” says Donna, now 51. “And I also mentioned to Dad I’d been getting blue flashes of light. He said I should speak to the optometrist.”

Donna went to see her local optometrist on her 49th birthday, and was told she too had macular degeneration.

“That wasn’t a very nice present,” she says. “I was very, very upset.”

Grant, too, was devastated.

“I knew it could affect the children, but I was still gobsmacked when Donna was diagnosed,” he says. “It was worse for me, her diagnosis, than my own. It really hurt me that she had it too.”

When Donna had her first set of injections, Grant went with her to support her.

“I held her hand, she was okay,” he says. “I was proud of her, she handled it really well.”

Donna has injections in both eyes every ten weeks, and because she is so young the family are hopeful that with the treatment, the condition could plateau. Being diagnosed also encouraged Donna to make some positive lifestyle changes.

“Stress is one of the risk factors,” she explains. “I’m a support worker, and I’ve also worked in palliative care. It’s hard, emotionally, plus I was regularly doing 12 hours shifts. I’ve cut back a lot.”

In some ways, both having MD has brought Grant and Donna – already close – even more together.

“I check in with her regularly,” says Grant. “I think it’s good to talk. We are both going through the same thing, we can share it.”

For Grant now though, the most important work is raising awareness of MD.

“It’s the biggest cause of blindness in New Zealand, and yet it can be treated if caught early, and you don’t have to lose your sight,” he says. “I’ve worked as an ambassador, speaking at events to help others understand it’s nothing to be afraid of. I tell everyone to get an Amsler grid and use it – no one visits our house without having their eyes checked on the grid!”

“Some people don’t even know what MD is until they’re diagnosed,” says Donna. “We didn’t, not until Dad was diagnosed.”

Both Grant and Donna’s message is the same – look after yourself, visit your optometrist regularly, use an Amsler grid once a week if you’re over 50, and if in doubt get a second opinion.

“Early treatment can stop the progressive and may give you a reprieve,” says Grant. “Especially if you’re young. There’s no need to be afraid.”

If you are worried about macular degeneration, you can find support and information at MDNZ. Visit www.mdnz.org.nz or call 0800 622 852