The usual defence of stories about Pākehā enraged by Māori ‘uppitiness’ is that the media are simply reporting people’s views. And that’s bollocks, says Aaron Smale.

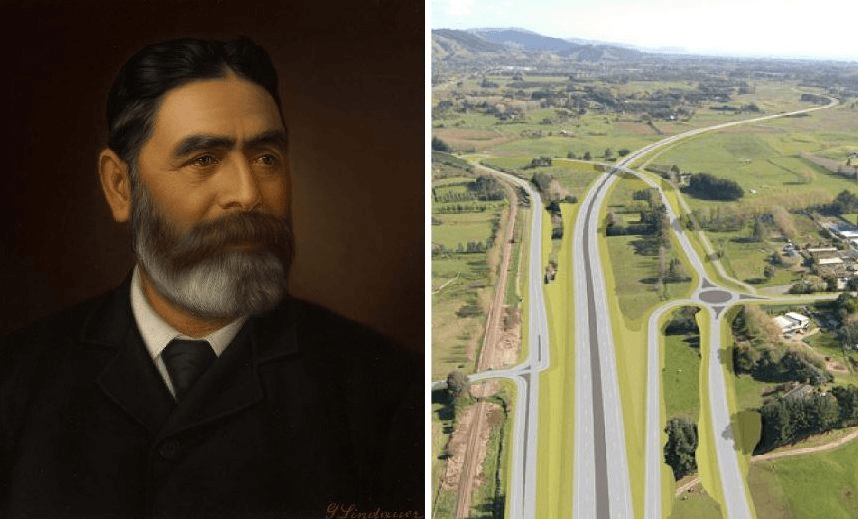

If you drive down the new expressway on the Kapiti Coast towards Wellington, when you get near Waikanae there is a slight bend. On the left a large concrete wall with Māori designs rises up the side of a bank. The wall is set against the land of Patricia Grace, who had to fight the government through the courts to retain the land she inherited from her ancestor Wi Parata Te Kakakura.

On the other side of the Expressway opposite the wall is another rise. It has headstones that are part of an urupa, or burial grounds.

Both pieces of land are the last remnants of what was once a large Te Ati Awa settlement that dates back to at least the time of Te Rauparaha. Oral tradition asserts that the high part of Patricia’s land was also a burial ground. The expressway effectively barrels through the middle of it.

None of this would be obvious to a reader of this morning’s Dominion Post newspaper or the Stuff website.

Instead, there was a story about how angry a couple of Pākehā were that parts of the old State Highway 1, now supplanted by the Expressway, had been given names that they had trouble pronouncing.

While there was response from local politicians and brief allusions to the history of the area, the story was dominated by these two Pākehā whingers, who insisted they weren’t racist but …

Two words sprang to mind when I read this story – ignorant and lazy. And I’m not just talking about the individuals quoted.

While everyone is free to express their opinion, the media make decisions all the time about what opinions are important and worthy of giving attention to and how those views are portrayed.

Which raises a few questions. Why are two individuals who are apparently completely ignorant of the history of the area they live in and the people behind the names referred to in the story given the front page of a major metropolitan daily to spout their ignorance? Why is this same media outlet not challenging them on their lack of effort to pronounce names that are in one of the official languages of this country? Why isn’t this media outlet giving more historical background to those names that are so offensive to a couple of ill-informed individuals?

This is a textbook example of the laziness and ignorance of mainstream media. It goes without saying that there are individuals who are going to be racist, ignorant, and a host of other undesirable qualities both openly and behind closed doors.

But too often the media seems intent on playing to this. They know there’s an audience for it, so they serve it up gleefully, knowing a great chunk of their audience will eat it up without asking any awkward questions.

As a newspaper journalist, earlier in my career I had a chief reporter (who still works for this particular media company incidentally, only now he’s an editor of another major daily) who reveled in the controversy over the seabed and foreshore. He would regularly get excited when a Pākehā redneck would ring up to express “outrage”. It was his favourite word and was his litmus test for any story’s merit. The more outrage the better and racial conflict was the best kind of story because it generated the most conflict and outrage.

But it was always tilted in the favour of the Pākehā enraged by the perceived uppitiness from Māori. Māori were made out to be grasping losers, while the outraged Pākehā was portrayed as the aggrieved Kiwi battler. It’s why Don Brash got such traction at the time.

The usual defence to this is that the media are simply reporting people’s views and everybody’s view is equally valid (although of course some are more equal than others).

Bollocks. In every area that the media cover there is a challenging of views that don’t add up, that stray from the truth, that can be contested. Except in one. I’ve worked in the media for going on 20 years. On a regular basis I see stories published about Māori issues where the journalist and the whole newsroom apparatus lets through statements and opinions that are either ill-informed or just straight out wrong. If such errors of fact were floated in the arenas of sport or politics or business they would be shot down in flames. Or ignored. But for some reason such rubbish gets through when the issue has anything to do with Māori.

This is when the media bothers to report on Māori issues at all.

There’s a term for this – it’s called institutional racism. While the media likes to portray itself as taking on powerful institutions, the media itself is one of the most powerful institutions in the political landscape. And it is also one of the most racist.

Walk into any newsroom in this country (apart from Māori TV) and you would be hard-pressed to find a Māori anywhere. Among the predominantly Pākehā staff you would find very little knowledge or awareness of Māori issues and history. The industry would not tolerate this kind of ignorance in any other area but for some reason it’s OK when it comes to Māori issues.

I once interviewed a kaumatua in the Hawke’s Bay for a history project about a group of hapu. This individual was one of the old-school Māori tohunga who learned his hapu’s whakapapa from childhood. His grandparents regarded the task of him learning their history as so important that he was not allowed to play with other children. Instead he traveled with them when they went to hui so he could absorb the whakapapa, politics and struggles of his people.

As he recounted this history – of war, confiscation, government dishonesty, the resulting poverty and sickness that stalked his whanau’s community well into the 20th century, a community where only 20% of the original population survived, the ongoing poverty of spirit that has led to high rates of suicide – after he’d recounted all this his voice finally cracked with emotion. It cracked when he said that the greatest thing that they’d had stolen was their history.

The carrying of that history sent him to an early grave.

The names along the Kapiti road, the names that so enraged a couple of Pākehā men, are about history. One of those names is Kakakura.

Kakakura is part of the name of one of the most significant politicians of the 19th century, Wi Parata Te Kakakura. His name references a deep history that reaches back before Pākehā arrival. He also donated the land that the present township of Waikanae sits on.

His descendent Patricia Grace is one of this country’s most revered writers and her novel Potiki is a prescient narrative that includes the taking of land for a road. It was Kakakura that took a case to court that ended with the chief justice dismissing the Treaty of Waitangi as “a simple nullity”.

Māori have effectively been fighting ever since to have that judgment overturned.

Perhaps the greatest opponent they’ve had in that fight is the media who seem determined to omit and wipe out the history of a people that are still here. But Māori are still fighting to retain and regain their history and have it recognised in small ways.

Like the renaming of a road after the government bulldozed an expressway through their burial grounds.

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.