When even the ‘woke’ are ignorant about Te Tiriti o Waitangi, it’s clear we need to make teaching its history compulsory in schools, writes Liam Hehir.

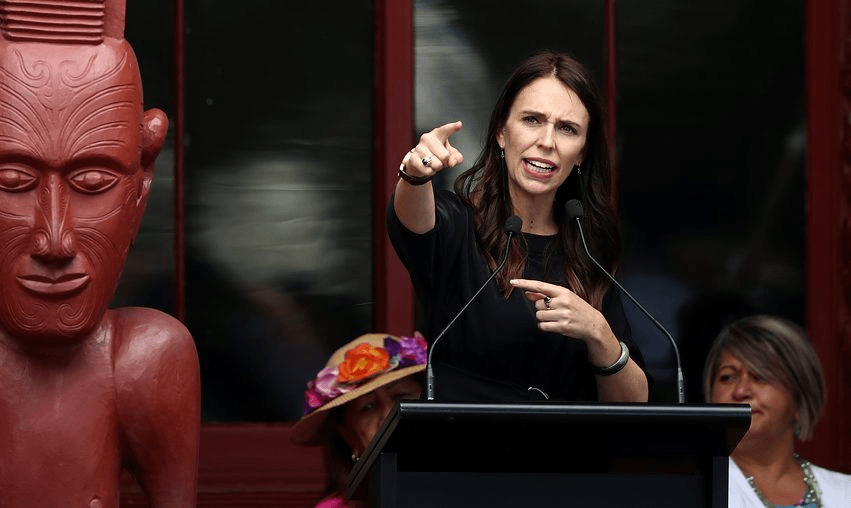

Sometimes something happens in the news that shakes you out of a bubble. I thought that making New Zealand history a compulsory part of the curriculum was more heavy-handed than the situation called for. The struggles of the prime minister to answer a basic question about the content of the Treaty of Waitangi illustrates that I was wrong in this.

It was a clarifying moment.

Not that we should be too hard on Jacinda Ardern personally. The same day, I asked ten people if they could summarise the Treaty’s contents. They were all clever people, but only one of them could even hazard a guess.

If asked off the top of my head, I would summarise the contents of the Treaty as follows: the first article deals with the establishment of the Crown here, the second guarantees Māori the continued possession of their lands and treasures while granting the Crown pre-emptive rights in Māori land and the third guarantees Māori the rights and liberties of British subjects. For bonus points, I would also add that the so-called “fourth” article, which was a verbal promise of religious liberty.

That’s not a perfect description by any means. I am sure plenty of people would object to how parts of that summary were phrased. It is, however, far better than any of the answers I received from anybody else.

I did not expect this. What was also unexpected was the fact that relative wokeness seemed to have little bearing on knowledge or ignorance about what is, whether you like it or not, the foundational basis for the existence of the country.

I had expected those who make a point of being sensitive to the Treaty to have a working knowledge of what was actually in it. If that sounds like a snarky point, it’s not supposed to. It genuinely surprised me.

Looking back, I realise that I was very lucky to go to little old St Peters College in Palmerston North. It is by no means a fancy school, but when I was there it always made a point of ensuring New Zealand history was present in the classroom. It was also – when I was there – blessed with social sciences teachers, which obviously makes a big difference.

In my seventh form year, the very capable Mr Erskine took us through New Zealand in the 19th century. This included things like the arrival of traders and missionaries in the early decades of the 19th century, the musket wars, the Treaty, the wars in Taranaki and the Waikato, gold rushes, land confiscations, “the long depression”, suffrage and the eventual establishment of the outlines of our present-day parliamentary democracy. Quite a bit of interesting stuff happened in these islands over the period and I see now that I was lucky to be instructed in it.

I like to think I would have learned about New Zealand history in my own time had my teachers been less interested in the subject. If I am being honest with myself, that would not have been guaranteed. Far from it, if my recent experiences are anything to go by.

I suppose one lurking suspicion is that the desire for more New Zealand history is also an implicit rejection of the value of teaching schoolchildren British history. That would be a mistake. What happened in the United Kingdom – particularly during the period of the English Civil War – is also important for anybody who wants to understand the nature of our institutions and how they work.

Anybody who has a good grasp of events of 17th century England and 19th century New Zealand will have a working knowledge of who we are and how we got here. Knowing that will set you on the path to being a good citizen. And if the point of compulsory schooling isn’t at least in part to form good citizens, it’s not really clear what the point of it is at all.