As some sense of normality returns to the streets of the US capital, the focus has shifted to political action – but this protest movement is not over, writes Abbas Nazari.

When 17-year-old Darnella Frazier began filming the arrest and subsequent death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers, she could not have imagined the movement her 10-minute video would spark. She uploaded it to her Facebook page in the early morning of May 26 and within hours it went viral, racking up millions of views. By nightfall, the first protestors assembled on the streets of Minneapolis close to where George was killed.

The next day protests spread to other American cities, drawing larger crowds, chanting the last words of Floyd, “I Can’t Breathe”. Within 48 hours, demonstrations formed in more than 100 cities, drawing hundreds then thousands of protestors, under the now common “Black Lives Matter” umbrella movement. Solidarity demonstrations spanned the globe, with marches in cities across New Zealand.

In the US, as demonstrations flared, armies of local and federal law enforcement officers, dressed in military style fatigues and protective equipment more suited for war, were deployed. Here in the capital, that included officers from the Department of Homeland Security, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Drug Enforcement Agency, Bureau of Arms Tobacco and Firearms, and the Department of Justice, as well as Military Police and the Secret Service.

Having never witnessed such an amount of firepower, I was even more startled to see unmarked federal law enforcement officers, dressed in paramilitary uniforms and wearing no identifying insignia, reminiscent of the Russian troops occupying Crimea. It was later confirmed that they were guards from the Bureau of Prisons, sent in as reinforcement to the already swelling number of federal officers in the vicinity of the White House.

The stunning images of militarised police clashing with demonstrators dominated the global news cycle. Pictures from American streets could be mistaken for some foiled revolution in some far-off dictatorship. The military hardware is a product of the 1033 Program, which transfers military hardware to local law enforcement. Since its inception in 1997, more than 8,000 local law enforcement agencies across the US have benefited from the programme, equipping themselves with tactical wear, military assault rifles, armoured vehicles and even tanks, totalling over US$7.4 billion. Following the police response to the protests surrounding the police shooting of Michael Brown, then president Obama rolled back the 1033 Program, only to be reversed by Trump in 2017.

We in New Zealand have recently had our own brush with armed police, with the trial of Armed Response Teams, and I congratulate Police Commissioner Andrew Coster on confirming the experiment will not be repeated. Armed police only serve to escalate a situation. America is proof of this.

The aggressive response from law enforcement seemed to escalate the situation, with each command to “Move Back” being met with resistance from an angered crowd. On the fifth day of protests, a 10-foot wall was built around the perimeter of the White House, separating the National Guard and military police from the demonstrators. The wall has now been partially taken down, and the parts which remain resemble a shrine to the black men and women and children killed at the hands of police. A president that had campaigned on building a “great wall” had finally built one.

In recent days, more than a fortnight after the killing of George Floyd, demonstrations have largely subsided. In the capital, crowds which numbered in the tens of thousands, now measure in the hundreds. Police barricades, road closures and armoured vehicles at intersections have been mostly been removed, and some sense of normality is returning to the streets of the capital. Shops are taking down the protective boards which were installed after the first night of looting, and military style posts are stationed only at the White House and not the surrounding streets as was the case last week.

Albeit in much smaller numbers, demonstrators continue to gather at the Lincoln Memorial, the Capitol, or the White House to show their support. On Wednesday, Philonise Floyd, George’s younger brother, spoke at a hearing of the House Judiciary Committee, and then joined the protestors at the White House, drawing an enthusiastic crowd. Demonstrators plan to continue their protest throughout the summer, leading up to a massive march on Washington planned for August. Organisers expect 100,000 demonstrators to attend the demonstration for police and justice reform, on the 57th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Longtime DC residents have told me that in a city which has witnessed countless demonstrations over the years, this one does feel a little different. It has lasted longer, drawn bigger crowds, and, importantly, the people participating are a mixed demographic, reflecting the broad reach of the movement. Former president Barack Obama, in a virtual town hall, remained optimistic that “there is something different here…and there is a far more representative cross section of America peacefully protesting” compared to the demonstrations of the 1960s. A Washington Post survey showed that three in four people believe the death of George Floyd is a sign of broader problems in the treatment of African Americans by police, and just as many people support the demonstrations.

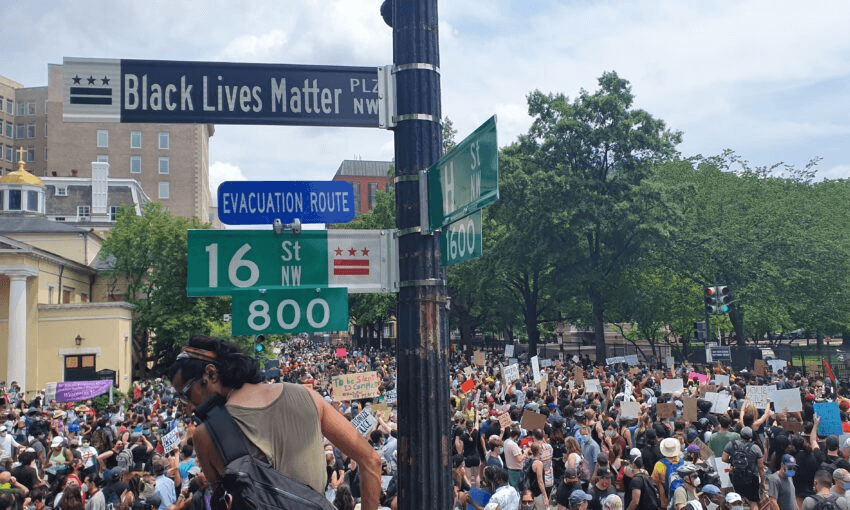

As the momentum from the demonstration subsides and crowds dwindle, the focus has shifted to the political and legislative arenas. The Minneapolis police chief has withdrawn from contract negotiations with the police union, seen as an obstacle to police reform in the city. Other police departments, including the New York Police Department (the nation’s largest) have also announced changes in police protocol, including a ban on chokeholds and similar neck restraints. And local councils in other cities have placed moratoriums on police funding, pending a systemic review. In more symbolic gestures, the DC mayor ordered the street directly in front of the White House be renamed Black Lives Matter Plaza, and painted “Black Lives Matter” on the pavement which can be seen from space. The Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture has also pledged to document and preserve the expressions of protest.

Residents, while supportive of the symbolism, hope that meaningful change can follow. A call to divert police funding into more community-led welfare initiatives and mental health services is currently before the DC council. Other jurisdictions are considering similar programs. While it is heartening to see endorsement for police reform coming from a wide array of stakeholders, if the slaying of George Floyd is meant to be a watershed moment in American history, officials at all levels must channel the anger and frustration of the past two weeks into meaningful structural change.

Abbas Nazari is a Fulbright New Zealand scholar in the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University, Washington DC.