Mahvash Ali writes about growing up in Pakistan, why she can never move back, and how her mindset changed with March 15.

If I had a dollar for each time I’ve been told to go back to where I came from, I would be there right now fixing the problems that made us leave in the first place. I was born in Karachi, Pakistan, and my parents moved to New Zealand about two decades ago. For 20 years, I listened to those horrible comments and never really let the reality of what they meant sink in.

My parent’s voice was forever in my head – “just ignore them”. Like many migrants from the Muslim world, they must have felt the remarks did not pose a serious enough risk. After all, where we came from is a country where the threat of Islamic extremism, sectarian violence and mass killings are the norm. By comparison, a racist comment means nothing.

When March 15 happened I had spent an equal amount of time in both countries. Since then I’ve woken up to the racism and Islamophobia that had been brewing in New Zealand for a long time.

The mosque terror attacks meant nowhere felt safe. It felt like time to pay heed to the question I’d been asked for years – why wasn’t I in Pakistan? Why weren’t all of us in the lands that we came from?

I’ve looked for answers for close to a year and I’ve decided I am staying firmly put in Aotearoa. There are myriad reasons for this, and none of them are comforting. They may be gross generalisations, but they are my reasons.

I love Pakistan – I just don’t see it as home. The values no longer make sense to me. Like many Muslim countries, Pakistan is a hotbed of foreign interference. While it might be an independent democracy on paper, the fact is overseas influence has never really let the country enjoy its freedom.

The United States’ unrelenting interest in Afghanistan means Pakistan has been on a constant state of alert since the 80s. The 2,400 kilometre Pak-Afghan border, called the Durand Line is tumultuous and penetrable. Whether the cold war or the war on terror, Pakistan has had to stand like America’s diligent front man.

It’s understandable: how do you say no to the big guy? But it has brought nothing but unrest to Pakistan and Afghanistan. There are currently 2.6 million Afghan refugees in the world, thanks to these twin wars. Afghanistan has the highest number of civilian deaths in a conflict, according to the UN. These everyday Afghans didn’t get to choose the bullet that killed them. Whether it’s the American forces or the local militia – the fingers on the trigger were indiscriminate.

Keep that in mind next time you’re wondering why Afghan refugees don’t go back to where they came from.

That’s the reason 71-year Haji Daoud Nabi moved to New Zealand. We now know him as the guy who said “hello brother” to his killer, the first of 51 men, women and children who were murdered in the mosque attacks.

Nine Pakistanis were also amongst those killed in the Christchurch shootings. They were not refugees like Nabi, but skilled migrants who left home for a better life.

Excessive brain drain is a grim reality that Pakistan has faced for decades. In 2019 alone, over 500,000 people left the country for greener pastures, according to one estimate. It’s not easy saying goodbye to a place you call home. However, often life and livelihood depends on it.

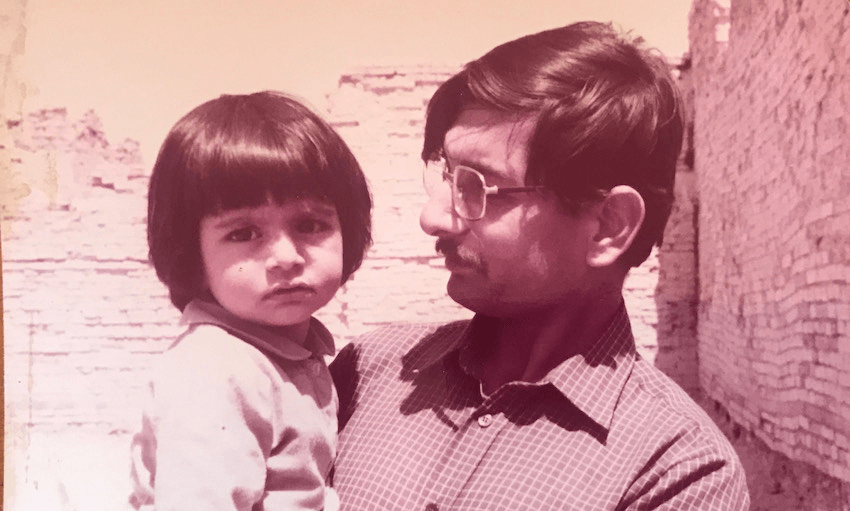

I can’t speak for others but I know my family left because it became too unsafe. My father was a senior police officer, and his promotions were directly proportionate to the size of our boundary wall, and the number of guards we had.

Each time he did his job right; there would be a new threat, each one more sinister than the last. That was my first lesson in telling the truth: you must be prepared to pay the price. By the time we migrated to New Zealand my brother and I did not know much of what happened beyond the 10-foot concrete walls of our home.

Sure, we went to school and social gatherings. But everything followed a strict protocol. How long we spent at a place, the route we took, who we met.

Sectarian violence was at its peak in Karachi at the time, the details of the crimes are too gruesome to share. Those at the helm of the savagery were sitting in foreign lands, bank accounts brimming with dollars, pounds and francs – yet they were calling the shots in Pakistan. No sooner did the authorities tackle one issue than another would pop up. Finally, it got too much for my family and we moved.

Two decades later, one of my favourite life experiences remains the first bus I took from Mt Roskill to the Auckland CBD on my own.

Between them my parents have three postgraduate qualifications. But they left their homeland so they could live and be honest somewhere their morals were honoured. For my parents, New Zealand is a safe haven. “Just ignore them” is the best advice they have for me when it comes to racists. However, I have decided that if I am going to continue living here, I am not going to ignore racism, xenophobia and Islamophobia.

Just because it’s a different kind of threat does not mean it’s any less evil. New Zealand is my safe haven too and it’s my job to make sure it stays that way. I know speaking the truth comes at a price. But I am going to take that risk.

It runs in the family.