Seven years on from his arrest, the extradition battle between Kim Dotcom and the United States reached New Zealand’s Supreme Court this week. RNZ‘s Kate Newton went to court to find out whether anyone seems to be winning.

Ron Mansfield – bearded and bespectacled – stood at a blond wooden lectern in the centre of the Supreme Court, rocking back and forth onto the balls of his feet, the minimal movements of a boxer tensing for a fight.

Above him the elliptical walls of the courtroom curved inwards, patterned with tesselating diamond-shaped wooden panels rising towards a huge oval skylight. It was possible to waste a lot of time calculating how many of the panels there were (2294) or what kind of wood they were made of (silver beech).

It was two days into the final appeal from Mansfield’s client, Kim Dotcom, against his extradition to the United States, alongside his former Megaupload.com executives Bram van der Kolk and Mathias Ortmann, and Mega’s marketing manager Finn Batato. If extradited, the US hoped to try them for what it claimed was a vast fraudulent conspiracy revolving round the website’s hosting of thousands of copyright-infringing files.

Van der Kolk and Ortmann’s lawyer, Grant Illingworth, had presented the first half of the men’s arguments in this appeal, and Mansfield – a senior criminal defence lawyer who’s had Dotcom on his books since 2015 – had been forced to wait.

Now the five justices filed into court after lunch, taking their seats round a shallow semi-circular bench, and the words Mansfield had been rolling round in his mouth all that time exploded out: “You can’t speed-date the Copyright Act.”

There was a pause. “What?” Supreme Court Chief Justice Helen Winkelmann said.

“You – can’t – speed-date – the – Copyright Act,” he repeated.

“Sorry, you can’t what, Mr Mansfield?”

“Speed. Date.” He launched into a definition of what speed-dating was. “I thought I’d try to keep it light but I may have missed the mark.”

Months of preparation had gone into these oral arguments and he’d started off by having to explain a joke. If explaining is losing, though, then everyone involved in the Megaupload case – on all sides – lost a long, long time ago.

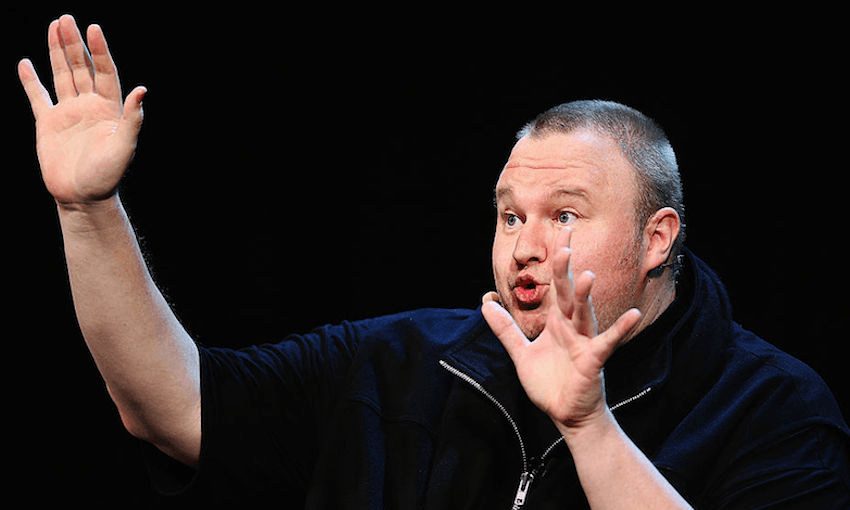

Mention Kim Dotcom nowadays and the most likely response is: “Is he still here?” The raid in which he and the other men were arrested on 20 January, 2012 has passed into New Zealand folklore. Footage shot on-board a police helicopter shows the chopper honing in on the pristine lawns and white gravel driveways of the mansion Dotcom was renting in rural Coatesville, north of Auckland. A rhinoceros sculpture comes into view as the helicopter lands.

The New Zealand police – at the behest of their FBI counterparts – threw everything they had at the raid. There were officers clambering over fences, there were AOS members toting guns, there were police dogs straining at their leashes, tails wagging. Dotcom was arrested in a safe room, where police said he had barricaded himself in but he claimed he was waiting patiently to be found.

What followed in the intervening years, after he was bailed back to the Coatesville mansion, was a cavalcade of parties and wild PR stunts. He hosted a bunch of Twitter nerds at an impromptu pool party. He released a music album at an estimated cost of $1 million and it immediately tanked. He gave evidence against former Auckland mayor John Banks that resulted in Mr Banks’ conviction (later overturned) for electoral fraud. He founded the Internet Party during the 2014 election, which crashed and burned and dragged Hone Harawira’s Mana Party down with it.

Through it all, a team of lawyers has fought the Megaupload extradition tooth and nail. Despite court orders in New Zealand and Hong Kong that have frozen some assets and forfeited others to the US government, Dotcom has still been able to spend $40 million on legal fees – his estimate. That money has paid for a string of QCs and other highly experienced lawyers here, as well as a team of US lawyers who fly in to New Zealand for every major hearing and will take over the case in the event that extradition actually goes ahead.

Money has literally bought him time. Arguments over the search warrants used to raid the mansion and whether it was sufficient for the US to provide only a summary of the evidence against the men, have both gone all the way to the Supreme Court – which ruled in the United States’ favour each time. That delayed the district court extradition hearing itself until late 2015, and appeals to the High Court and Court of Appeal have taken a further three years.

The Supreme Court is supposedly the last line of appeal, but the ultimate decision – if the court deems the men eligible for surrender to the US – lies with the justice minister, currently Andrew Little. That decision can then be judicially reviewed, at least as far as the Court of Appeal and possibly all the way back to the Supreme Court. Unless the Supreme Court overturns the eligibility finding that three lower courts have already confirmed, neither side is even close to victory.

New Zealanders might have forgotten Kim Dotcom is here, but that doesn’t mean he’s leaving anytime soon.

The morning this latest hearing began felt like a reunion, as a roll-call of familiar faces arrived at court. There were a dozen lawyers in all, with piles of binders in every conceivable colour arranged in front of them. Grant Illingworth stood at the counsel’s lectern, shuffling his notes and occasionally leaning back to stare up into the courtroom’s dome. Mansfield sat behind him at a second row of desks, staring at his laptop and rubbing his bottom lip with his index finger.

Seated next to Mansfield was Elizabeth Dotcom, 23, newly-minted law school graduate and new-ish wife of Kim, dressed for the part of junior counsel in an impeccable suit. Her hair was incredibly shiny. Later on she was introduced to the court by Mansfield: “Mrs Dotcom, who doesn’t appear formally, but is seated at bench.”

Outside court, journalists who had stuck with the case for over seven years joked with camera people and drank coffee and pointed out lawyers and the three other accused men to the uninitiated.

Finn Batato was the first to show up, heading straight inside where he shook hands with the various lawyers and peered over his own lawyer’s shoulder at his notes.

Bram van der Kolk and Mathias Ortmann were next to arrive. Ortmann is maybe the unluckiest of the four: he arrived in New Zealand for a week-long holiday at the start of 2012 – just in time to get – and is still here seven-and-a-half years later. He described himself as “one of the rare tourists who gets to spend hundreds of hearing days in New Zealand’s courts”. Court orders have limited his expenses and he’s had to live with van der Kolk and his wife the entire time. The two men are tight: they show up at every court hearing together and sit next to each other.

Inside, the public gallery was packed with law students and a few curious members of the public. As the week went by, the crowd thinned out, but there was one man, with dark hair and thick-rimmed glasses, who showed up each day and took a seat near the back of the public gallery. Was he with one of the legal teams? “Just an interested spectator.” He’d filled pages and pages of an A4 pad with notes though. Was he from the Motion Picture Association of America, which is very keen to see Megaupload and its ilk prosecuted? The slightest beat of a pause. “Just an interested spectator.” That was all he would say.

The one conspicuously absent person was Kim Dotcom. He seemed to be in Wellington somewhere though. He tweeted a photo of his legal team having a drink together on Wednesday evening, and sometimes during breaks Mrs Dotcom would slip away from court, crossing the road in spiky heels and dodging her way through Lambton Quay commuters to an unknown destination.

On the first morning, Illingworth made reckless promises about sticking to time, setting out a legal ‘roadmap’ he swore to follow. “I’ll try to indicate where we are in the roadmap as we go.” The roadmap turned out to be a twisting, turning thing. It wound its way through old cases – McVeigh, Cullinane – that have become touchstones in the case and the owls seated at the bench nodded at them in recognition.

At times Illingworth diverged from his own path, wandering down by-ways and ducking into cul-de-sacs, and had to be dragged reluctantly back to the main route by the justices, who found themselves cast in the role of perturbed back-seat drivers.

Other times it was the justices themselves who insisted on the detours, including a long stop to consider whether a work only had to be copyrighted in the US or if a New Zealand copyright also had to exist.

Trying to hold the arguments in your head was like grasping at sand, or thinking about black holes for too long. Or maybe like trying to pitch a tent in a gale: just as soon as you thought you had one part of it tied down, another bit would flap loose, flailing in the howling legal winds.

What are the issues, exactly? Buckle in.

The US Department of Justice allegations go something like this. Megaupload.com was one of the largest hosts of illegal, copyright-infringing music, movie and software files in the world. Sure, it didn’t have an index, but users posted links on third-party websites that did have a search function, and directed other users to the files.

Not only did Megaupload allow this, it actively encouraged people to upload infringing files by paying financial rewards to users who posted popular files – which tended to be the infringing ones. When copyright holders issued take-down notices to Megaupload, it would delete the individual link the copyright holder had identified, but not the file itself or the myriad other links that led to it.

All this was a deliberate, carefully planned conspiracy to make money by infringing copyright on a mass scale, the argument continues. The criminal counts in the US indictment list, among other things, racketeering and wire fraud. In order to extradite the men, the US must show there are comparable crimes in New Zealand that the men could have been charged with if the alleged offending had happened here – although this is actually another point of legal debate. Crown lawyers, on behalf of the US, have first pointed to criminal offences in the Copyright Act, and also to offences in the Crimes Act, such as dishonestly using a document and accessing a computer system for a dishonest purpose.

Megaupload, for their part, argue that the website was created in 2005 as a cyberlocker – a digital file-storing and sharing site a bit like Dropbox. They did not upload the infringing files, they did not own or possess the files in a legal sense, and the only reason they did not take down infringing files was because there might be entirely lawful, non-infringing URLs linking to that file (which, if it was a duplicate of another file, was only stored on Megaupload’s servers once). Yes, they paid rewards, but only for smaller files, and the rewards were for increasing traffic to the website, not specifically for uploading infringing files. What they did was simply “good business”, Illingworth told the Supreme Court.

Megaupload’s users may have breached copyright but the website itself was protected from liability through ‘safe harbour’ provisions in the Copyright Act that don’t allow internet service providers to be prosecuted, even if they are aware of infringing material on their site, so long as they take steps to delete or block access to it as soon as possible. Deleting only the infringing URL was standard industry practice and was sufficient to meet that test, they argue. And, even if the four men are liable, there just isn’t sufficient evidence to justify extradition.

Nor can the US fall back on the Crimes Act, the men’s lawyers argue. All of the allegations rest on proving copyright infringement and, in New Zealand, the legal remedies for that are in the Copyright Act alone – you can’t just turn around and go charge-shopping using the Crimes Act.

Also, the entire case is unfair, they say, because the defence has been limited in what evidence it can present to court, hasn’t seen the full US evidence against the men, and New Zealand’s police and spy agencies screwed up the preparation for the raids with some illegal spying and some dodgy search warrants anyway.

Throughout the hearing, Chief Justice Dame Helen Winkelmann and Justice Dame Susan Glazebrook dominated the questioning. Justice Winkelmann wore large, round, black-rimmed glasses that made her face look all eyes and magnified a high-beam stare that she fixed, unblinking, on whichever lawyer stood at the lectern. The stare was so compelling that it could trick whoever was caught in its headlights into continuing to talk, just to fill the silence.

Justice Glazebrook filled the role of the everywoman, probing every definition and bit of jargon. At one point, trying to find an analogy for digital infringement, she devised a parallel universe where half the justices were petty crooks.

“If Justice France had written a novel and has some 50 copies of it on her computer and I know it’s her novel and I know it’s copyrighted and I take it and I print it up and I sit on the street corner and sell it for $10 haven’t I dishonestly and without claim of right taken a document and used it?

“If Justice Winkelmann and I decide that we’ll hack into Justice France’s computer to take the document…”

“The problem is that that’s not what happened,” Illingworth said.

Justice Joe Williams joined in: ” I guess the correct analogue, is Justice Glazebrook prints out 10 copies, and agrees with me that I’ll bring my wheelbarrow to the door of the Supreme Court, and I’ll convey them to the street corner, knowing that she’s going to be selling them. And her and I have some sort of agreement that we’ll share the proceeds.”

Also not quite right, IIllingworth said. “They are providing the photocopier, someone else comes along and uses the photocopier. They are not saying, please use our photocopier for illegal purposes.”

Mansfield’s speed-dating joke on Tuesday might have fallen flat but he dusted himself off. He wanted the court to develop a long-term relationship with the Copyright Act, he said, and he kept his word. Nearly all of Wednesday turned out to be a comprehensive tour of the Act and its history. A group of high school kids who’d filed into the public gallery as part of a tour of the court slumped in their seats and stared at the ceiling. This was no speed-date; this was a death-do-us-part situation. Chief Justice Winkelmann called it “careful analysis”.

His arguments, and the US response, turned on the definitions of a few words: possession, communication, distribution. Had Megaupload ever really “possessed” its users’ files by simply hosting them on its servers? Was allowing access to an illegal digital copy of something communication, or was it distribution? Without “possession”, communication wasn’t a specific crime but distribution was. The Crown argued distribution included communication. Mansfield argued communication referred specifically to digital forms. Distribution was for tangible copies – which could include a copy of a book on a Kindle that you then gave to someone else, for example, but not an intangible file hosted on a server somewhere in East Virginia, US.

Kim Dotcom was still absent from court but his Twitter account had lit up. He posted a gif of the Incredible Hulk, captioning it “Ronnus Day 2”, and later posted a photo of his legal team captioned with nicknames – Ron “Ronnus” Mansfield made another appearance, alongside fellow lawyers Simon “Hulk” Cogan and Katie “Google” Creagh. Another 20 or so Dotcom tweets followed on Wednesday and Thursday, outlining his take on the court hearing so far and repeating his lawyers’ arguments.

Twitter is the only place the public hears from Dotcom these days. Filmmaker Annie Goldson, whose documentary Kim Dotcom: Caught in the Web premiered in 2017, pinpoints the ‘Moment of Truth’ during the 2014 election campaign as a turning point for him.

At the Moment of Truth, US whistleblower Edward Snowden and American investigative journalist Glenn Greenwald claimed, via videolink, that New Zealand was part of a Five Eyes spying programme called XKEYSCORE, which intercepted not just metadata but full text emails and other communications via a wire-tap of the Southern Cross cable.

The allegations were amazing, but Snowden did not offer documentary proof that New Zealand’s involvement had gone beyond a preliminary stage. Dotcom used the event to promote his new company, Mega, and afterwards got into a shouting match with journalists, telling them: “Do your job.”

He seemed to withdraw from public life after that, Goldson says. “I did feel the public did turn against him.” There was a corresponding dwindling of public interest in the Megaupload case, too. “Kim is such a big personality that when he became less visible, I think public interest [in the issues] faded.”

Whatever people think of him, and no matter how arcane and drawn-out the legal proceedings get, it’s important to remember the role Dotcom’s case has played, Goldson says. “There are a lot of questions about the original raid, from fairly sloppy processes from police at best, to overreach [of their power].

“He did reveal some of the workings of our intelligence systems, the police, our government. Those are important things to hear about our democracy because they are things we don’t get to hear about often. In that way, he probably paid us all a favour. He was able, for a while, to seem like the underdog.”

Today was meant to be the last day of the hearing but – as is the way with all Megaupload hearings – it was running over time and Monday was scheduled as an extra day.

It wasn’t over by a long stretch, anyway. The Supreme Court would reserve its decision, probably for months. In an earlier hearing, Crown lawyer David Boldt had suggested that, depending on what the court decided, seven years might only mark a half-way point. Seven more years! The ice caps might have melted by then.

Outside, pedestrians walked past the court, oblivious to questions of possession and Parliament’s intention and the tangible and the intangible.

The underdog himself had moved on, preoccupied this morning with US war-mongering over Iran. From somewhere in New Zealand, he sent another tweet: “Here we go again.”

This article first appeared at RNZ, and is republished with permission.