There are 55,000 houses in flood zones in Auckland, many of which were inundated in the recent deluge. Some of these houses were just a few years old. Why are we continuing to build in these areas – and can we prevent it?

This story was first published on Stuff.

Diane Tieni wasn’t bothered when the rain first came.

“It started out on the road, and we thought nothing of it. Roads got swamped, that’s fine.”

A little later, one of her children said, “Mum, look outside.”

Things were no longer fine. Diane saw cars floating in the street. Her neighbours across the road were already up to their waists in water. And the floodwater was lapping at Diane’s door. She watched it creep inside the house, across the plush new carpets, soaking into her furniture as the family rushed to lift everything they could to safety.

By the time the rain finally stopped around midnight, the basement was flooded out and the entire ground floor was awash in a foot of water.

Many, many families in Auckland have a similar story to tell of the January 27 flood: frantic attempts to shift possessions out of harm’s way, wading to safety through chest-high floodwaters, evacuations through top-storey windows.

What sets Diane and her neighbours in Ventura St apart from many others, though, is that these weren’t older houses, built in flood zones before anyone had heard of climate change.

Diane’s house is just over three years old.

She, four of her children, and two of her grandchildren, were among the first to move into dozens of brand-new Kāinga Ora townhouses in a mixed housing development known as Māngere West, in south Auckland. An upbeat brochure from late 2019 shows a beaming Diane holding up the keys to her new home.

Hundreds more houses, including KiwiBuild and open-market homes, will eventually replace older state housing.

Te Ararata stream flows down the middle of the development, and wider Māngere is among the lowest-lying land in Auckland. Together, these factors mean that the development lies almost entirely in a flood zone.

Diane did not know this when she and her family moved here from the cold, older-style state house they’d been living in. “The excitement was, we were getting new-build homes – warm, safer for us,” she says.

“We were just happy with what we got offered, and I think that’s a very common mentality with us low-income families. We don’t question these things. We don’t question where it’s built.”

‘A disaster waiting to happen’

Since the beginning of 2016, Auckland Council has granted resource consent for 9,220 new dwellings in flood plains (areas where runoff from waterways will flow) and 4,295 dwellings in flood prone areas (natural and human-made features like depressions, dips and gullies where rainwater can collect).

There isn’t data for the number of dwellings consented on land where there are also “overland flow paths” – the routes taken by stormwater when the normal stormwater system is overwhelmed.

Stuff has analysed Auckland Council data of the flood risk areas the council predicts would be inundated in a one-in-100-year rainfall event, together with Land Information (LINZ) data of building locations.

This reveals just over 55,000 existing buildings in these areas, most of them residential.

Many of the newest houses will not be included, as they do not yet appear on LINZ maps.

Zoomed-in sections of the map reveal how flood-risk areas are pepper-potted throughout the Auckland region.

Take the suburbs surrounding Eden Park in central Auckland, where half of some streets are designated at-risk, while their neighbours remain beyond the danger zone.

The rain on January 27, which was an all-time record, exceeded the one-in-100-year risk. NIWA estimates it was a one-in-200-year event.

But firsthand observations from residents and others on the ground are that the flooded areas still matched the flood risk maps very closely.

The map below shows the footprint of the Māngere West development, and the existing buildings in the area (many of which are meant to be demolished and replaced).

Māngere resident and Monte Cecilia Housing Trust chief executive Vicki Sykes was, until recently, part of the Māngere Community Housing Reference Group that raised concerns with Kāinga Ora – which led the development – about the flood risk in the early days of the development.

Kāinga Ora was “very aware” that the physical stormwater and other infrastructure was outdated and needed work, Sykes says. But many other groups were involved, including the council and developers. “Everyone wanted to fix the issue but everything was siloed and nobody had the budget on their own.”

Kāinga Ora deputy chief executive Caroline Butterworth said Māngere was “well known in the construction sector as an area of Auckland where ground stabilisation is required prior to the construction of new homes”.

“Specific to the Mangere West catchment area we completed a Storm Water Management Plan and implemented flood mitigation measures including the installation of storm water basins in Ventura Street, the upgrade of storm water pipes, installation of new and upgrade of existing outfalls.”

Butterworth also points out that the rainfall “exceeded the one-in-100-year event that infrastructure is designed to withstand in urban development”.

But Sykes still believes that whatever was done was not enough. “There’s anger at how on earth can we collectively allow this kind of mistake to happen. And just huge sadness for the families that’ve been affected by this, many of whom won’t have contents insurance.”

The biggest mistake was building on a flood plain at all, she says.

“It was a disaster waiting to happen.”

When the worst-case scenario keeps changing

The "one-in-100-year" event that councils, developers and engineers are all meant to plan for is a slightly misleading turn of phrase. What it actually means is that, in any given year, there is a 1% chance of the event occurring (known as a 1% annual exceedance probability).

Belinda Storey, a senior research fellow at Victoria University's Climate Change Research Institute, says the problem with that, is that the risk has been calculated at a fixed point in time. “If you’re currently in a 1% AEP, that is only going to go up with climate change from 1% to 2% to 4%.

“When I first started the research I’m doing, I assumed that the change in the probabilities for rainfall would happen decades later. [But] those probabilities are changing quicker than I or anyone predicted.”

Her solution is the same as Vicki Sykes’. “We need to stop building in flood plains. I recognise that there’s a significant housing shortage, so we need to be building mid-rises in those parts of Auckland that are on higher ground.”

Some newer developments on flood plains did withstand the January rain. Among them was the huge, master-planned Northcote development on the North Shore, which encompasses state housing, KiwiBuild homes and open-market houses.

In Takanini, on the southern outskirts of the city, thousands of homes have been built on flood plains since a special housing area was created there in 2014. The empty streets on the map below are now full of recently-built family homes.

Andrés Roa, the director of engineering consultancy AR & Associates, worked on the stormwater and flood mitigation design for one section of the Takanini development.

It was a “real technical challenge”, which involved rearranging and lifting the entire site to redirect the flow of water into a new stormwater conveyance corridor – essentially a man-made stream servicing the entire housing area.

Instead of pipes, Roa and his team designed an open stormwater system, where water both drains along swales – wide, shallow grassy channels built into the street berms – and collects in recharge pits. The system avoids the stormwater outlet blockages that can cause back-flooding into properties, and the permeable surface of the swales slows the water’s flow.

Residents Stuff spoke to say they were unaffected by the recent rainfall, with the system working precisely as it was meant to.

But despite the apparent success of that strategy, Roa believes it was the exception, not the rule.

“Every other time, you really want to work with your natural topography and natural features as much as possible. As a first port of call, those [flood risk] areas should be avoided at all costs.”

Stopping the development deluge

Climate change minister James Shaw has a one-word answer when asked if development should still be going ahead in flood zones: “No.”

So if everyone – from stormwater engineers to climate change researchers to politicians to community advocates – is so unequivocal, why does it keep happening?

“There’s probably a number of reasons, one of which is that there’s no national direction to councils not to authorise construction on flood plains,” Shaw says. “And because there’s a housing crisis, councils are feeling the pressure to expand housing stock, and I think some of them will have just been making those trade-offs.”

Many councils are also “fairly poorly resourced”. “I suspect that a lot of council planning capability was built in a world where we didn't have the effects of climate change being felt as markedly as we are now.”

Work on reforming the law is under way. The Natural and Built Environments Bill, which will be the main replacement for the Resource Management Act, is at select committee stage, along with the Spatial Planning Bill, which will require long-term regional spatial strategies.

“They’ll probably be quite directive to councils about where not to build in future,” Shaw says.

But he points out they won’t solve the problem of what to do about houses that already exist in flood zones. The issue of "managed retreat" – the deliberate removal or relocation of at-risk dwellings and communities – is what the third Act of the trilogy of reforms deals with: the Climate Change Adaptation Act.

That Bill hasn’t even gone to Cabinet yet, and Shaw doesn’t put a date on it. “It’s an incredibly complex piece of work. I’m more interested in getting it right than I am in rushing it.”

Even once the reforms are passed, though, the actual implementation will take years, he says.

“So there’ll still be a gap during which time you could see some development that’s inappropriate. So we are considering the possibility of interim direction as well.”

That interim direction is something Auckland councillor Richard Hills would love to see.

Hills chaired a council planning, environment and parks committee meeting last Thursday that agreed to go ahead with a review of all the council’s planning rules and tools. The council would also seek an urgent meeting with government ministers about whether special emergency powers were possible in the aftermath of the flooding.

Several councillors asked at the meeting whether it was possible to revoke recent consents that had been granted for building in flood plains. Hills told Stuff he didn’t think that was legally possible, but emergency powers might allow the council to pause current applications that have been lodged.

The council is often hampered by the current law when considering applications for building in hazard zones, Hills says. “As long as you can prove you can do it, generally you have to permit it. So it’s whether you could do a plan change to prohibit, is the question we need help with from the government.”

He, too, wonders whether a one-in-a-100-year risk, measured and modelled at a point in time, is still fit for purpose. “That measure, just by looking out the window, feels like it’s not an accurate way to describe these events any more.”

The tide still rises

After weeks of rain, the sun is finally out in Ventura St and Diane Tieni and her neighbours have laid their salvaged possessions outside to dry.

There is no structural damage to the house, so for now, she and her family are staying put. “I would love to move, but where am I going to move to with the housing crisis?”

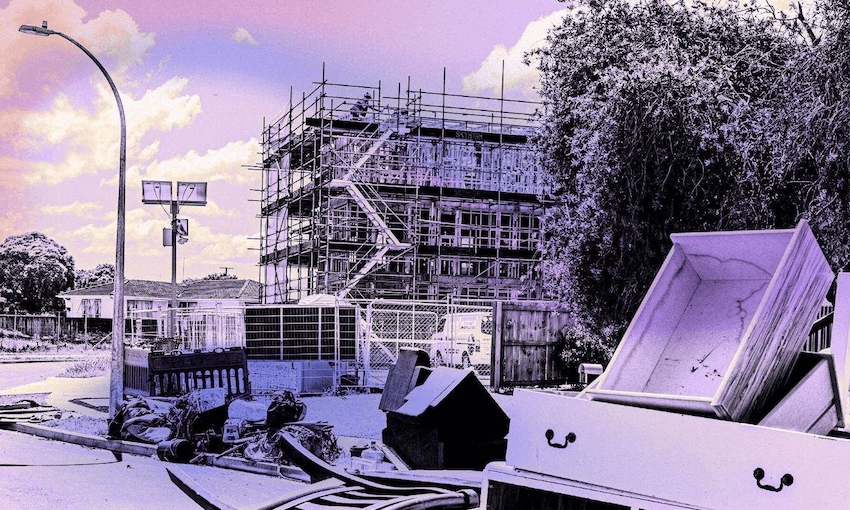

Around the corner on Bede Pl, mounds of mattresses, wrecked furniture, ruined carpet, and other belongings beyond saving, teeter on berms outside yellow-stickered houses.

Next door, silhouetted against a bright blue sky, builders clamber along the wooden framework of more townhouses under construction.

A Kāinga Ora branded hoarding is attached to the fence: “New warm, dry homes are coming, Māngere.”