The history of tattoo art in Japan is deep-rooted and complex – and so is the cultural aversion to tattooed bodies, explains Brian Ashcraft, the author of a book on subject.

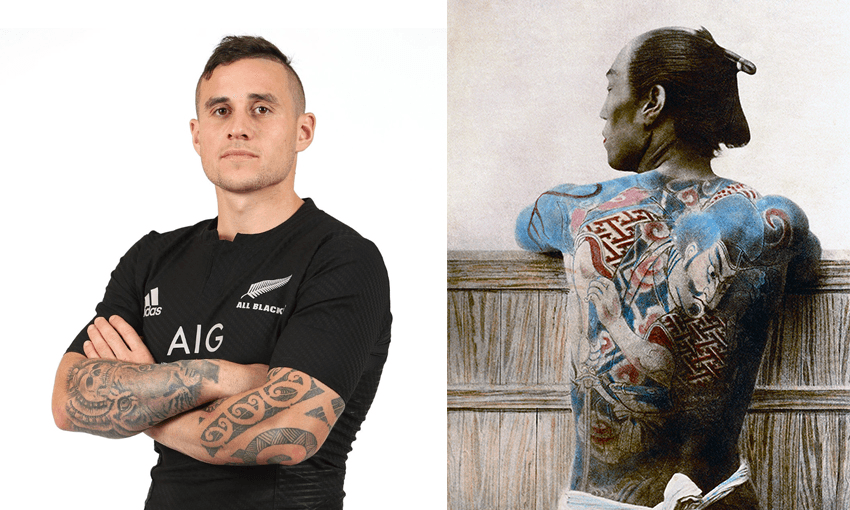

Tonight, when the All Blacks take the field, they’ll likely be covering up. In order not to run afoul of Japanese cultural niceties, players are considering hiding their tattoos. In Japan, tattoos have long been looked down upon, seen as something brandished by organised crime. But it wasn’t always this way.

According to a 3rd-century Chinese account of Japan, the Japanese were covered in tattoos to mark social status. Japanese fishermen were inked to protect themselves from harmful sea creatures. The Japanese terracotta clay figures known as haniwa, dating from 250-710 CE, often have markings on the body that some believe are tattoos. It is thought that the ancient Japanese used tattoos much in a similar way to other indigenous people around the world. However, once Chinese culture, which looked down upon tattoos as disrespectful to one’s parents, started to influence Japanese culture, tattoos were used as punishment. In the 5th century, for example, the emperor had a man’s face tattooed after his commoner dog killed an imperial bird. In the centuries that followed, punitive tattoos, originally a Chinese ideal, were meted out in Japan, typically for conmen or those who had violated the public’s trust. The punitive tattoos ranged from stripes on the arm to the words “dog” or even “evil” on the forehead. Tattoos became synonymous with crime.

By the Edo Period (1603 – 1868), Japanese society was highly stratified. Great importance was put on the Confucian ideals of filial piety. Nothing could be more disrespectful to one’s parents than defiling the body they bestowed. Today, Confucian thought doesn’t dominate the Japanese consciousness, but those concepts of filial piety certainly linger. However, it was during the Edo Period that people really started to rebel and express themselves with ink. The first expressive tattoos were simple dots but evolved in vows of passion with people tattooing their names on their lovers. Tattoos continued to evolve with people beginning to cover up their punitive marking with designs as well as those who hadn’t been punished wanted to get inked out of their free will. By the 18th century, the full-body, intricate Japanese bodysuit tattoo design had been codified. Japanese tattoos were – and are – elaborate works of art.

However, tattoos were typically worn by blue-collar types doing manual labor. They got tattoos to protect their bodies. Firefighters, for example, sported tattoos of dragons, because, in Japanese culture, dragons are able to control water. Covering oneself in dragons might give a firefighter the necessary courage to battle the blaze. Japanese tattoos have deep meanings, and the designs reflect the beauty and culture of its artistic tradition. The designs have meaning and reflect the seasons, the religions, and culture. But, for the upper class in Japan, tattoos were gauche, low class, and disrespectful. There was zero appreciation of the country’s rich tattoo tradition. After numerous failed attempts that were largely ignored, the Japanese ruling class finally banned tattoos in 1872 – a ban which lasted until the Americans legalised them after World War II. During this period, tattooing was driven underground. The only work tattooers could get was inking members of the yakuza, who appreciated the imagery, the machismo, and how the designs intimidated regular folk.

Because tattoos were driven underground, regular Japanese people didn’t see them as much, which made it more surprising and unnerving when they did. Blanket bans on tattoos appeared at public baths, swimming pools, and hot springs. Tattoos of any sort were shunned. Tattoo discrimination became a cultural norm. But all sorts of people in Japan have tattoos. While writing my book Japanese Tattoos: History * Culture * Design, I meet an array of inked Japanese people – yes, there were the obligatory, yet polite, gangsters, but I also met health care workers, musicians, moms, businessmen and more. You cannot pigeonhole the type of people with tattoos, because doing so leads to problems. Case in point: In 2013, visiting Māori scholar Erana Te Haeata Brewerton was turned away from a hot spring in Hokkaido because of her traditional tā moko tattoos. “I’m not used to being treated like that,” Brewerton told AFP at the time. “My moko tells other Māori where I am from.”

And this is the problem with Japan’s position on tattoos. Not only does it misunderstand and misappreciate foreign tattoos, but it also does the same thing for its own tattoo tradition. Because of this, when tattooed Japanese celebrities appear on Japanese TV or in Japanese TV, their ink is either hidden or airbrushed out. However, when tattooed foreign celebrities like Johnny Depp or David Beckham appear on Japanese TV, their tattoos are fully visible. In the past few years, with the influx of foreigners, you are increasingly bound to see tattoos on the streets of Tokyo and Osaka. Japanese people are getting more and more used to seeing tattooed foreigners, at least.

If Japan is going to host the world in international competitions such as the Rugby World Cup or the Olympics, it needs to be more accepting of different cultures. The All Blacks are erring on the side of caution, hoping not to offend viewers. Their real Japanese fans already know which team members are inked and probably do not care. But for the locals, covering up tattoos is the norm. When in Japan, do as the Japanese. But what if the Japanese are wrong?

Texas-native Brian Ashcraft has called Osaka home since 2001. He is a senior writer at gaming site Kotaku.com and the author of five books including Japanese Tattoos: History * Culture * Design and most recently, Japanese Whisky: The Ultimate Guide to the World’s Most Desirable Spirit.