Earlier this week a trade unionist wrote for The Spinoff about the rise of public service strike action under the Labour government. Today former Green Party education spokesperson Catherine Delahunty shares her perspective.

I have heard more than a few complaints that teachers did not strike under National, so why are they doing it now? As education spokesperson for the Green Party for nearly nine years, I spent many hours with teachers and their unions, examining legislation which undermined the quality public education system. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that over the last nine years the teaching profession was punchdrunk by a sustained political assault on their mission. Hence the exodus, and the struggle to replace the workforce. The recent teachers strikes are a last-ditch effort from a profession with legitimate expectations of fundamental change, relief and reward.

At the very beginning of the Key government we went straight into urgency to debate their National Standards legislation. This was a disastrous policy which attacked the core principles of teaching and immediately teachers and their unions were forced into battle. Some schools resisted it, and many protested, but the policy of measuring and comparing primary students and schools via league tables became the norm. The damage was done. Remember: National Standards was never debated or discussed with schools and was passed into law under urgency.

Then came Education Minister Hekia Parata’s attempt to increase class size, on the grounds that size doesn’t matter. This was resisted by parents as well as teachers, who knew that larger classes would mean teachers had less time with each child. The combined effort of both groups led to a humiliating back down by the minister, but the fight took up a lot of energy. In the middle of these debacles the Christchurch earthquakes struck and schools became hubs for communities and for children in shock. The government took the opportunity to impose a reform on Christchurch schools which went way beyond closing or repairing the damaged schools and a battle for survival took place, characterised by official mismanagement and insensitivity towards a traumatised school network.

But this was just the beginning of the relentless changes and ideologically driven “reforms”. The charter schools championed by ACT and National were provided with resources other schools could only dream of and a range of experiments of highly variable value were begun. Military school and privatisation at public expense were put in the same basket as tangata whenua efforts for educational self determination, while 90% of Māori students remained in underfunded local English-medium schools. Teachers’ major focus was privatisation rather than wages and conditions.

This all happened while house prices in Auckland went nuts and teacher aides did not get centralised wage funding. Early childhood education was a privatised mess and franchises created baby barns with government encouragement, while Kohanga Reo and Playcentre struggled.

At the Education and Science Select Committee some seemingly random government bills kept turning up but they all facilitated reduced student and teacher representation in the tertiary sector, school boards being able to run several schools, the replacement of the Teachers Council by a new less representative body, the Teachers Code of Ethics becoming the Code of Conduct… on it went. This all took place in a global context of educational “reform” known as the GERM (Global Education Reform Movement), which led to a rewrite of the Education Act and an Update Bill to incorporate the COOL (Communities of Online Learning) concept – basically a digital replacement of the teacher.

The actual rewrites were without vision and did not reflect many student or teacher ideas or a common purpose that lifted the debate. They generated deep concern from people like the Children’s Commissioner and the Ombudsman from a children’s voice and rights perspective. Meanwhile the learning support system continued to be broken and teachers were leaving the profession in despair.

The new laws failed entrench a commitment to teaching te reo Māori and a lack resources hampered efforts to move schools beyond assimilation models. Kotahitanga, a programme that supported teachers to address bias against Māori, was frozen.

During the lead up to the 2017 election the Greens, NZ First and Labour all committed to addressing these issues, and affirmed the necessity of valuing teachers in every way, including financially.

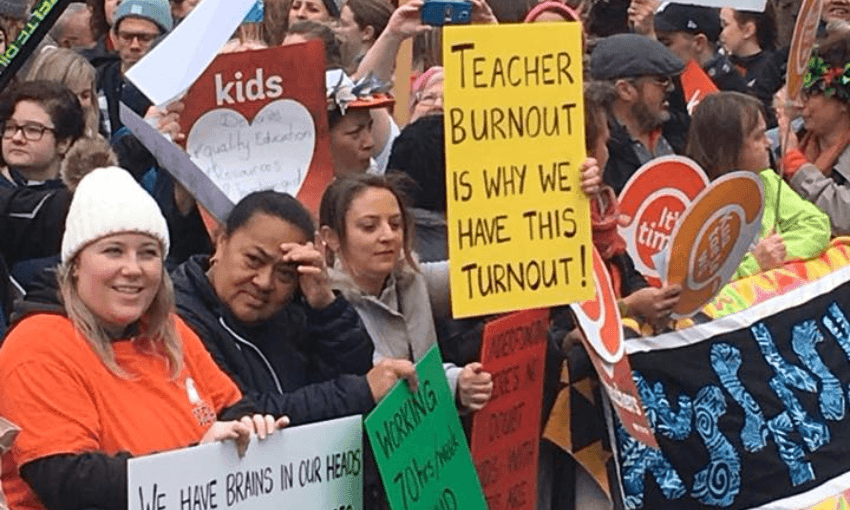

It is therefore not a surprise that teachers who had been fighting for public education are now fighting for the workforce who make it possible. The battle to value the principles of public education is no longer needed – the government gets it! But as well as rebuilding ECE, strengthening learning support and more good work, teachers want a decent offer in terms of wages and conditions. I feel tired just recalling all the fights of the last decade – I can only imagine how they feel.

Claims of the need for fiscal restraint are not going to cut the ice. The Budget Responsibility Rules, which I have personally always opposed, should be dropped so the state can invest in crucial sectors which have been bled dry. The rhetoric of kindness starts with providing schools with what our children need and valuing teachers. Listen to the issues behind the strike, listen to the teachers.