At the Auckland High Court, I watched a trial unfolding as a crucible of modern gender and sexual politics under the spotlight of unprecedented media coverage, writes Nicola Gavey.

See also:

Defending the indefensible: On the Grace Millane trial and victim blaming

Justice for Grace Millane. Now let’s now change how we talk about blame

How to put the hurt, rage and grief for Grace Millane to good

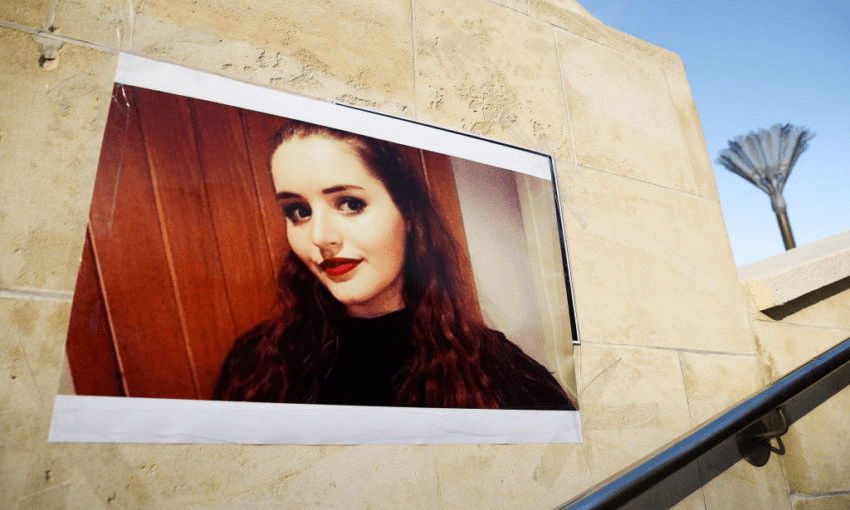

One year ago Grace Millane was murdered by a 26-year-old man in his inner city Auckland apartment. She met him for the first time early on the evening of Friday December 1. They had drinks in town and then walked back to his place. Grace died in the confines of his hotel-style room, either that night or early the next morning, on the day of her 22nd birthday. She died due to sustained and forceful pressure applied to her neck by the man who was convicted of her murder last Friday.

The trial unfolded as a crucible of modern gender and sexual politics under the spotlight of unprecedented media coverage. The verdict is a relief, which could reassure us that we are becoming more attuned to understanding the dynamics of men’s violence against women. But the defence strategy in this case reveals the persistence of systemic misunderstandings and blind spots about what happens at the interface of sex, gender, power and violence. Given these misunderstandings have been widely reported, not always with the fullest context, they have potential to reinforce social attitudes that provide a cover for men’s violence against women and girls.

Sitting in the dock through his murder trial, the defendant looked like an ordinary man. Tidily dressed with a shirt and jacket, he possibly could pass for the successful young businessman that he pretended he was. One thing we learnt for certain about this man, is that he is an extreme liar. Lying is his modus operandi. He lied to everyone, it seemed, about everything. Beyond that, and because of that, it’s difficult to know with confidence what kind of man he is. But the testimonies I heard portrayed him as a tinderbox kind of man. The kind who is needy and wounded at the same time as he is drawn to masculine dominance and control. Bred of this volatile combination, a tinderbox man is capable of flaming into violence at the slightest spark of offence.

We don’t do a good job in New Zealand of facing the reality of men’s violence against women. We beat around the bush, and tone it down with non-specific terms like “family violence” or euphemisms like “sexual harm”. Terms that hide the particularly gendered dynamics of crimes that hurt and kill girls and women. In doing so, we don’t recognize the way that tinderbox men, like the man who killed Grace, get to be way they are. We don’t see that they are a product not just of their troubled personal histories, but also of the messages society hands out to men about their rightful place in the world. We heard from one witness, a woman he’d been messaging for months but never met in person, about what he told her he liked sexually: “feet, dominating and strangulation”. When she asked him why, he told her it made him feel “more superior and in control”.

Many people have described this trial as flowing with all the same old victim-blaming myths that operate in rape trials. In many ways it did. But in other ways, it had a different twist that deserves attention.

The perils of blame and shame was a key theme in lawyer Ron Mansfield’s speech to introduce the defence evidence. “The younger generation,” he was reported saying, “does not adhere to this ‘pressure on us to appear normal’, and they can teach us about their refusal to accept these old concepts.” On the surface, his words sound progressive. They resonate with feminist “sex positive” discourse, which calls for women’s rights to sexual pleasure and experimentation without judgement and shame. They fit with queer theory’s critique of the oppressive grip of societal ideas about what is “normal”. And they appear to embrace inclusion, as they reject the way that some sexual practices and identities have historically been marginalized and stigmatised.

Professor Clarissa Smith helped the defence case as she matter-of-factly told the jury that BDSM is “a common practice, and [that it] was not an interest driven only by men”. Building on these expert claims, defence lawyer Ian Brookie told the jury in his closing address that choking is “just something people are doing now as part of the leisure activity of sex. [The defendant] is just a young man doing what women want him to do in the bedroom.” Earlier in the trial, giving evidence via a video link from the UK, Professor Smith had explained that “amongst younger women we are seeing a greater sense of their own aims, their own sexuality, of being prepared to actually say what they would like, we’re no longer living in the era of, you know, ‘lay back and think of England’”.

But this picture of a happy new sexual landscape is woefully blind to the ways it remains shaped by gendered dynamics of power and domination. While Professor Smith’s portrayal is true for some women, it’s not the full story. Many women still navigate their sexual lives in circumstances that are too constrained by sexist norms to make this kind of self-determination possible. The social science literature is full of studies that reveal a far less utopian sexual landscape for young heterosexual people. It shows that both young men and young women still expect that men will pressure women to do things sexually they don’t want to do. And it shows some men still talk about sex with women in terms of conquest. Of course there are many exceptions, but these general patterns have remained strong and constant in research spanning four decades.

As one study, just published this year, concluded: “Although some researchers have suggested that the cultural gender script is beginning to value greater sexual agency for women in mixed-sex relationships”, their survey showed that “many men still use SV” [sexual violence]. Some young men they interviewed normalized sexual violence. As one said, “there were a lot of times where it was just like obviously she didn’t want to do it, or something like that, and I’d obviously insist, because it’s nice”. Numerous studies show this kind of attitude is alive and well among some young men. Likewise, numerous studies document women’s experiences of sexual pressure and coercion from men to have sex when they don’t want it, and to engage in sexual acts that they don’t want. Talking about heterosexual anal sex with young people, the authors of a 2014 UK study said, “women seemed to take for granted that they would either acquiesce to or resist their partners’ repeated requests, rather than being equal partners in sexual decision-making”.

As well as presenting a misleading impression of modern sexual culture as an egalitarian playing field, Professor Smith and the defence overlooked the sexual double standard, which is another an old thorn in the side of women’s sexual freedom that is still alive and well. Again, research shows lots of different ways in which women are still judged more harshly than men are for their sexual expressions and behaviour. In our own local research on sending nudes, secondary school girls and boys recognised a sexual double standard. As one boy told us:

“Yeah, if girls are known to do that kind of thing they get like named certain things that obviously they don’t want to be called. Guys can be viewed as different. Like, you’re the cool guy if you send that kind of stuff where girls, can be doing exactly the same thing and get a really bad reputation”.

While Ron Mansfield and Ian Brookie made a show of denouncing victim-blaming, and embracing progressive, supposedly new, sexual habits in their courtroom speeches, they certainly didn’t refrain from making use of the old sexual double standard when it came to cross examining the women who had had sexual or sexualised connections with the defendant, or when they dredged up details about Grace Millane’s sexual past. They laboured gratuitous questions that appeared to have had no other function than to shame and stigmatise women. As their tactics showed, sex positivity for women still lies precariously in the shadows of sexist sexual shaming. Those defending men of violence against women can draw on it when it suits their argument. But they can quickly jettison sex positivity for women when it works better to dredge up the old conservative ideas that undermine women’s testimonies and reputations.

By arguing that Grace was killed during an act of “rough sex” that she had consented to, the defence reveals just how problematic it is to apply the language of BDSM to sexual encounters that don’t take place within the bounds of communities of practice that emphasis careful explicit consent. Without direct, explicit and unambiguous evidence from the person on the receiving end that they consented to “violent” sex – which is what the convicted man described happening – the only safe and reasonable assumption we can make is that it was sexual violence. In Grace Millane’s case, there is no evidence of her consenting to anything. There was not even forensic evidence to confirm that she had had sexual intercourse the night she died.

During the trial, the defence approach also revealed a disturbing ignorance about the normal patterns of gendered fear, danger and safety in situations where men are violent towards women.

Research just published, on people’s experiences of feeling scared during sex, found “substantially more women than men reported that someone had done something during sex that had scared them”. Being held down, and being choked were some of the experiences people described. Even within organised BDSM communities, which have explicit guidelines to promote consensual and “risk aware” behaviour, non-consensual behaviour does occur.

I know that many of us witnessing this trial felt the ache of sadness for Grace and her family, and sadness about the other women and girls who have been killed and harmed by men in their lives. I also felt fury. Fury at the way our society, and most other societies around the world, still promote norms for men and masculinity that can so easily turn toxic and fuel violence. Fury for the misogyny that still channels some of the worst expressions of men’s violence towards women, including those they purport to love. And fury about how people within the upper echelons of our criminal justice system are willing to draw on this misogyny to try and cover up other men’s violence against women.

A month before he killed Grace Millane, the convicted man had told another woman he met through Tinder that he loved her. He had met her only once before, earlier in the year, but they had not been in regular contact. That night after hours of talking and drinking he went on to violently assault her as she lay on the bed in his shoebox apartment. Facing her feet, he pinned down her forearms with all his weight, and sat on her face with so much force that she could not breathe. She was kicking and struggling with all her might, but he kept pressing down on her. She was terrified she was going to die. Earlier in the evening, he had told her things about himself that scared her. At one point in her evidence, she stopped short, and said she wasn’t allowed to speak about that. So the full context of what he had told her seemed to have been suppressed, distorting how much the jury and the public could understand about the context of her fear.

Yet, as all criminal lawyers should know, on the 3rd of December last year the new crime of “Strangulation or suffocation” was added to the Crimes Act. Experts increasingly recognise non-fatal strangulation as a particularly dangerous form of violence committed by men against their intimate partners. As a 2016 New Zealand Law Commission Report noted: “The psychological impact on victims can be devastating. It is often said that, while the abuser may not be intending to kill, he is demonstrating that he can kill. It is unsurprising that strangulation is a uniquely effective form of intimidation, coercion and control.”

Repeatedly, Mansfield told this witness her experience was not what she said it was. She was told that she had “exaggerated” what happened, that she wasn’t really scared, and that she was being “dramatic”. He asked her repeatedly why she did not leave earlier, why she did not raise with him her concern about him having suffocated her. And especially, he asked why she maintained regular text message contact with him over the following month. “You wanted to portray yourself as a bit of a victim”, he callously told her. As he repeated this line of “questioning” ad nauseum, it suggested he understood little about the dynamics of men’s violence against women. His line of questioning suggested he did not understand how threat manifests for a woman who has been violently assaulted. He appeared not to comprehend that a woman might behave differently in assessing danger, safety, and risk. He appeared not to comprehend that she might have a more attuned ability than him to read the signs of danger, that that this woman had accurately assessed the defendant as a tinderbox man, prone to unpredictable explosive violence.

As this woman pointed out through her evidence, the defendant knew a lot about her and her movements. She knew he would be able to find her, and she worried that if she cut him off cold he would show up in her life. Encountering a violent man on a Tinder date is a modern form of risk. We need to be able to turn our heads towards understanding what survival skills would look like in that particular kind of mediated relationship. As this woman later placated him, keeping him at a safe distance, while managing to avoid him in person, she was able to diffuse or delay the risk of him stalking her or turning up in person in her life. These actions make perfect sense as a modern form of self-defence for our modern technology-mediated social world.

Near the end of the trial, I heard a man leaving the public gallery say that the lack of evidence of defensive wounds on Grace’s body was a major problem for the Crown’s case. For him to have been able to infer that this might suggest she was consenting to being strangled was for me the final straw in showing how little is understood about men’s violence against women. As defence lawyers would know, lack of evidence of defensive wounds does not mean a woman did not attempt to defend herself physically. But we also know that women cannot always defend themselves physically because they are literally paralysed by terror. We also know that sometimes in the face of violence a woman will attempt to survive by going still in the hope that the man attacking her will have a change of heart or think his job’s done and stop in time. Anyone who can put themselves in the shoes of a woman who is being restrained and strangled by a man who is much bigger than her should be able to understand these things.

In delivering their unanimous guilty verdict, the jury in this case made the right decision. The evidence was substantial, intricate and compelling. But in my view the smoke and mirrors defence, which has been broadcast around the world, stands in the public record as a shameful repository of ignorance about the intricacies of sex, gender, power and violence. Sadly, that works against the very progress we need to eradicate patriarchal messages about men’s sexual dominance and entitlements that help to create tinderbox men in the first place.

That is why, despite the risk adding to the unfair scrutiny on Grace Millane’s life and the women who gave evidence in this trial, I am writing about it. Not only did they not deserve the convicted man’s fatal and life-threatening violence, they also did not deserve to be met by such ignorance and disrespect in a court of law.