Growing up disconnected from her father and his side of her family, Tamsyn Matchett never understood her Tongan identity. On Saturday at Mt Smart stadium she sang the Tongan national anthem for the first time, surrounded by her Tongan brothers and sisters.

I grew up not completely sure how Tongan I was. Actually, I wasn’t even sure I was Tongan at all. Like many other mixed Pasifika, my ethnically ambiguous looks mean I am often mistaken for a dozen other nationalities. It never really bothered me much. My friends often joked I was the Cliff Curtis of our rōpū.

Growing up as a brown kid in a pālangi family on Auckland’s North Shore, however, it wasn’t always easy having your identity muddled, and it made it almost impossible for me to feel at home with who I was. I think I often felt embarrassed by my own displacement and ignorance and that prevailed into adulthood.

Two years ago after completing a young Pasifika leadership course at work, I decided to look for my dad. Until this point I hadn’t considered that reaching out to my biological father was an option. I didn’t want to disrupt another family’s reality, didn’t want to upset my own, and didn’t feel I had anything to gain.

Having my own mixed Pasifika child changed my outlook. Considering how she might relate to her roots and the impact that might have on her own identity means a lot to me. Also, the more I learned about Pasifika cultures, the more I realised I had everything to gain. So, armed with only Dad’s name, I jumped on Facebook to search for him.

Fast forward two years, having met numerous aunties, cousins, nieces, nephews and siblings; cuddled my Tongan nana; eating my dad’s double smoked ribs despite being a vegetarian; and reconnecting with almost every Tongan I know, I found myself amid a sea of red, supporting a team I had very little knowledge of prior to the beginning of their 2017 Rugby League World Cup campaign – Mate Ma’a Tonga.

My father is from Vaini, a small village on the south west of the island Tongatapu, with a population of less than 3,000. According to Dad, Tonga players Sika Manu (c), Daniel Tupou and Ben Murdoch-Masila are our cousins of some description. And not just the players: many members of the crowd and apparently even one of the police officers on duty at the game are relatives of mine. This is how close MMT fans feel to their team and the reason for such fervent following.

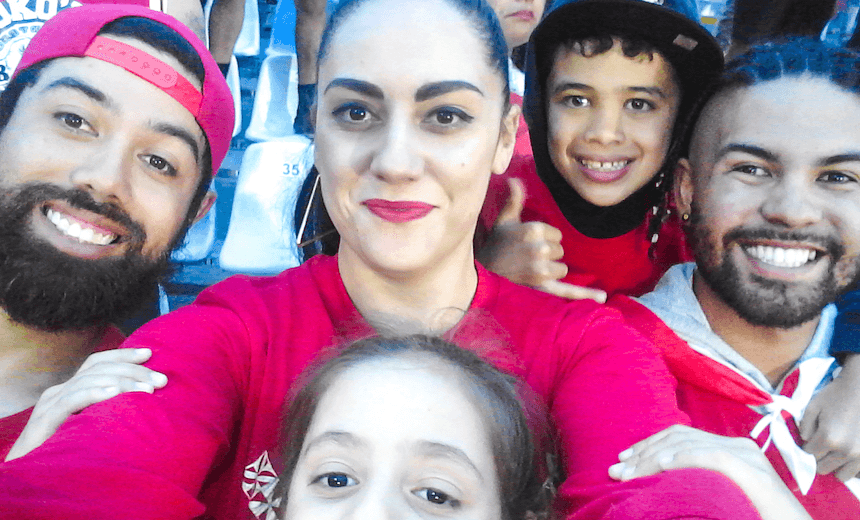

Sitting with my two younger brothers, my two sisters-in-law, my niece and nephew and my daughter and partner in the south stands at Mt Smart Stadium, all covered in MMT merchandise waving our Tongan flags high, we joined the 30,000 strong crowd to sing the Tongan national anthem ‘Ko e fasi ‘o e tu’i ‘o e ‘Otu Tonga’. I don’t know if anybody else had the pleasure of singing their homeland’s anthem for the very first time that night, but I did. The feeling of belonging was overwhelming and I will never forget that moment for the rest of my life. The only appropriate way to follow that experience was witnessing the Sipi Tau, a Kailao – Tonga’s version of the haka.

The first half of the semi-final could have been exceptionally deflating. We struggled to penetrate a strong English defence and the tries we conceded were a huge blow. I am a notoriously competitive person and probably a bit of a sore loser at times, which makes me a particularly bad spectator. But this crowd made it impossible for me to feel anything other than hope and pride no matter how dire things appeared.

Every unsurmountable moment was met with glorious song and collective voices chanting behind us urging the boys on. I can’t recall how many times I heard the beautiful Tongan woman next to me softly pray to God for a Tongan victory. As MMT remained scoreless, children and elders alike were unified in determination, in such a display of Pacific collectivism and community spirit that regardless of the outcome our support for the men on the field would be unfettered, loud and powerful.

The second half of the game will go down in history. Well, the last 10 minutes will. There is something to be said for a team that has the ability to force such a change to a semi-final scoreline in such a short period of time. And also for the fans who believed in that team’s ability to do so throughout those first 70 minutes: that is dedication, love and loyalty at its best. This game was the pinnacle moment for a small island nation punching so far beyond its weight, exceeding the expectations of a sport that makes money off individual talent but remains reluctant to invest in their collective opportunity to represent their own.

Pacific nationalism is sadly misunderstood in a country that benefits so much from Pacific communities (and not only in sport). This was especially evident when commentators, players and coaches took aim at Tongan ‘defectors’ Jason Taumololo, Sio Siua Taukeiaho, Manu Ma’u and David Fusitu’a. To assume these players were given equal opportunity to represent either side, Kiwis or MMT, misrepresents the imbalance of that choice. The same could be said about Andrew Fifita and the treatment he received after opting for Tonga over the Kangaroos.

It also shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the culture of these players, the responsibility they hold to their families and their heritage, and the unsustainable nature of Pacific Island rugby (both union and league). Of course Island players benefit from academies and school scholarships as well as support from high profile clubs in both New Zealand and Australia. That is the reality of under-investment in sporting infrastructure in the Pacific; until now, playing for an Antipodean team was the only sustainable career option.

As a Tongan who grew up essentially as a pālangi girl from The Shore, it has become increasingly easy for me to identify inequity. I was raised with the privilege afforded to a white family, but was still brown enough to be treated differently. I still recognise that difference today, even more so now I am connected to my Tongan family. I also recognise that the inequity experienced by my Pacific tokoua goes far beyond sport.

As a nation, we still need to address the inherent gaps in our understanding of Pacific Island cultures. The media’s reporting of the post-match celebrations and the heavy-handed behaviour of some police is testament to that fact. Allowing Pacific communities space to celebrate collectively is at the heart of being an Islander.

I am hopeful that the display of courage from those players to represent their loved ones for a pittance in comparison to what they were being offered is a wake-up call to those who need it. Imagine how much rugby union and league, and sport in general, would benefit if those players with Pacific heritage were not only eligible but were supported to play for their home nations more frequently. I know one group of people who would show up in truck-loads, ready to sell-out stadiums to back their small island nation at every opportunity.

Attending the semi-final to support MMT was a real milestone for me and my growing sense of identity as a Tongan who was born and bred in New Zealand. I am so proud of the Tongan community in New Zealand, and all those around the world who took this opportunity to celebrate what it is to be Tongan, waving flags from cars, painting fences red and white, and unifying in a way that will go down in sporting history. I am also desperately proud of my Tongan family, my dad, my aunties, my nana, and my brothers and sister and their children, who after 30 years of not knowing me have welcomed me and my daughter with so much love and kindness.

This experience reminded me of something a Samoan colleague said to me two years ago that was the inevitable driver for me to search out my family. She told me it was my birthright to know my family; that as their blood ran through my veins it meant I belonged to them and deserved to know them. It meant that I was Tongan, I was a Pacific Islander, and that above all else I should be proud of that. And on Saturday I really, really was. Mate Ma’a Tonga – Die For Tonga.

The Society section is sponsored by AUT. As a contemporary university we’re focused on providing exceptional learning experiences, developing impactful research and forging strong industry partnerships. Start your university journey with us today.