I saw Neil as soon as I was allowed. He was sitting alone on the step of his bach, roll-your-own cigarettes in yellow-stained fingers, flagon of beer nearby. Were his hands shaking, or does my imagination add that detail?

The Sunday Essay is made possible thanks to the support of Creative New Zealand.

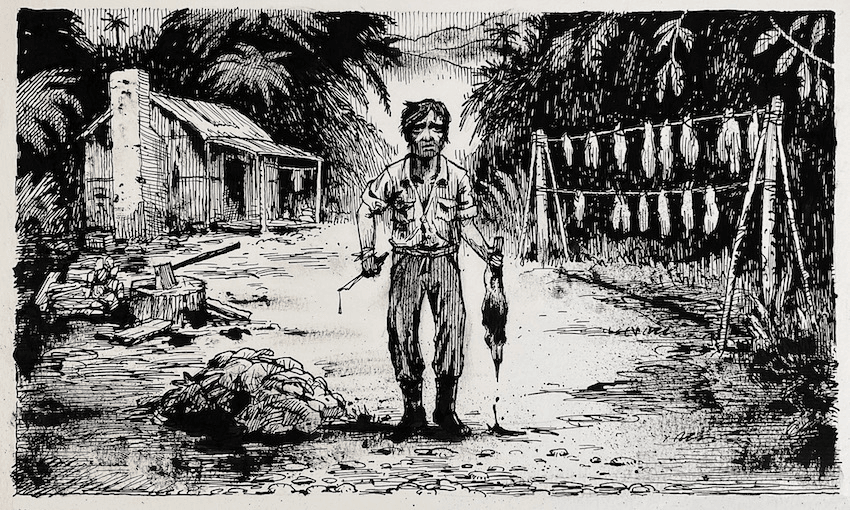

Illustrations by Gavin Mouldey.

This essay discusses addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder and wartime conflict. Please take care.

A bit under 70 years ago, my Uncle Neil came home from Malaya.

There are three untruths in that sentence. Not the name “Malaya”: that’s what it was called until independence in 1963. But his name wasn’t Neil; he was my uncle only in the honorary sense sometimes applied to close neighbours in the 1950s; and what he came back to wasn’t home any longer. You might add a fourth falsehood: it wasn’t really he who came back.

Neil was a regular soldier in the New Zealand Army. He’d enlisted because the local cop warned him that if he didn’t straighten himself up, he was bound for jail. He was too young to fight in the mess that was Korea, but just the right age to see off the communists who were supposedly threatening an outpost of the British Empire, and therefore the whole Free World.

The second world war had seemed such a morally pure and simple conflict. There was evil, and our boys fought against it. Now our boys were supposed to be shooting some of the Malayan Chinese who had helped them combat part of that evil, but who were now reduced to a label: Communist Terrorist, CT. The cold war was underway, and anything labelled “communist” was automatically a threat to lives in Tirau and Temuka.

By the time Neil got there, the CTs had been knocked around by better-armed Commonwealth forces, and had mostly retreated into the jungle, with the stated aim of avoiding confrontation until Malaya became independent, and they could morph into a political party.

Not good enough. Special forces were sent in to find and destroy them. Our own just-formed SAS featured; some of their commanders kept a scoreboard on which they chalked up the running total of CTs they’d killed. “The New Zealanders reached peak performance,” one report enthused. That was the climate into which Uncle Neil moved.

I don’t imagine he was fussed at first by the political nuances. I was a kid, a decade-plus younger than him, but I recall his excitement during training; his eagerness to be posted overseas. You have to remember how exotic any sort of OE seemed in the 1950s. And I recall the other young men and women who would share the front steps of his little bach behind his mother’s house during his army leaves, drinking beer, smoking, laughing, even singing. At the age of nine, I couldn’t imagine a better life.

Away he sailed, with the rest of the 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment, after a parade through Wellington streets. He was almost two years in Malaya: no home leave, but the bars and possibly the brothels of Kuala Lumpur and other cities. He wrote to his mother, and she read the letters to my parents. “I’m right as rain … I’m hunky-dory … I’m a box of birds.” The phrases that let her sigh and keep hoping.

There were other things in the letters. There must have been, in spite of military censorship. Because when we heard that Neil was suddenly coming home, that he’d even more suddenly arrived, my father made me wait a day before I was allowed to rush over. He went, for half an hour only, and said little when he returned. That night, I heard him and Mum murmuring behind their closed bedroom door until I fell asleep.

I saw Neil as soon as I was allowed. He was a disappointment, sitting alone on the step of his bach, roll-your-own cigarettes in yellow-stained fingers, flagon of beer nearby. He grunted a greeting, said hardly anything unless I asked a question, filled and refilled his glass. Were his hands shaking, or does my imagination add that detail?

I do know that when I finally asked the question I’d been aching to – “Uncle Neil, did you ever kill anyone?” – he grunted, “Don’t be so fucking silly.” I didn’t feel rebuffed; I was secretly thrilled to be party to such an adult word.

I noticed something else and told my mother about it when I got home. “Uncle Neil smells, like he’s spewed up or something.” She wheeled on me, so suddenly that I flinched. “It’s none of your business!”

Over the next weeks, we’d hear Neil talking, mumbling to himself. I couldn’t make out the words. Dad called me away from the fence where I was eavesdropping and told me I’d feel the back of his hand if I tried that again.

Neil’s friends came a couple of times, but there was no singing. Figures from the RSA visited and that seemed to help, for a little while, anyway. I’d glimpse a hand resting briefly on the young man’s shoulder, hear a voice murmur, “You take it easy, pal”. Male tenderness, I realised, decades later.

Another month or so, and he’d begun talking to himself in the night as well, out on the bach step. Sometimes his mumbling erupted into a choked shout. My father or mother would come into my bedroom, check I was OK, tell me that Uncle Neil was taking a while to get over things.

Then after three, four months, he was gone. The windows of his bach closed, the front step empty. “He’s got a job with the rabbit board,” his mother told mine. “A really good job.”

A month later, Dad and I drove out to see him, in our little Austin A30. Maybe I nagged till my father gave in. Maybe he thought my presence might soften Neil. I remember an interminable, twisting, climbing shingle road that became a track, our car grinding over stones till the rabbiter’s fibrolite hut appeared.

A clothesline stood beside it, rabbit carcasses dangling from the wire. Neil was there, a knife in one hand, a pile of furry bodies on the ground beside him. Dad got out of the car, told me to stay where I was. As he walked towards Neil, the younger man picked up a dead rabbit. His knife moved, something spilled from the carcass, then Neil was pinning it up on the wire with the others.

My father and Neil shook hands, began talking. After ten minutes, I got out of the car, stood kicking stones across the scanty dry grass, making it clear how bored I was. More minutes, then Dad came back to me. “There’s a creek over there, son.” He pointed past the tankstand. “Go and find something to do.” I stared in protest, and he lifted a hand. “Just do it, please.”

I set off, kicking at more stones. I stopped and called out, “G’day, Uncle Neil!” I don’t think he replied. I don’t think he looked at me.

The creek was a couple of mud holes. I dropped chunks of clay on tadpoles, practised saying “fucking” under my breath. When my father called me, he was by the car again, and Neil had gone. We bucked and scraped back down the track, and Dad didn’t say a word.

Neil died half a dozen years later, when I was at high school. I’d lost interest in him by then. He died before his mother, and I sensed that some sort of shame of moral failure came with that fact. I don’t recall a funeral. I do recall Dad telling Mum how the rabbit board had to get a digger in to bury the hundreds of beer and whiskey bottles.

These days, we have the words and some comprehension of what happened to Neil and others like him, in a campaign where the guerrillas they killed included teenage girls and where bombing raids on CT camps sometimes left shredded baby items among the smouldering wreckage. We eschew judgements of inadequacy or weak moral fibre now. We make some attempt to understand, to heal young men and women who’ve faced violent death and moral ambivalence.

A 2020 survey of over 1800 past or present New Zealand military personnel suggested that at least 30 per cent suffered from stress, and probably one-third of that number are or have been afflicted by some form of post-traumatic stress disorder. Steps have been taken to provide financial and counselling support, under The Veterans’ Protection Act. Health providers are urged to check whether patients have a relevant military background. We try to help.

There was no help like that for my Uncle Neil. A little while back, in the aftermath of the hearings that so severely compromised Aussie Victoria Cross winner Ben Roberts-Smith, I read fellow Australian Vietnam veteran Dave Morgan’s book, The Invisible Trauma: Coping With PTSD. In Morgan’s narrative of anxiety, the inability to trust or love, bodies shaking, nightmares, flashbacks and addiction, I recognised our broken young neighbour straight away.

I’m sorry we – I – couldn’t do anything for you, Neil. You deserved so much better.