Away tries to be a space drama and a family drama, but fails massively at both.

There’s a good reason why outer space is such a popular setting for fiction: the stakes are so obvious. Just off camera, just off the page, is an endless void that can kill your protagonists if a single thing goes wrong. Death is a mechanical failure away, and everybody in the audience understands that. Families, for a similar reason, are also a popular subject for fiction. Everybody has family drama of some kind; everybody can empathise with other people’s family drama. The problem with new Netflix show Away is that it tries to equate space drama with family drama, and it doesn’t work at all.

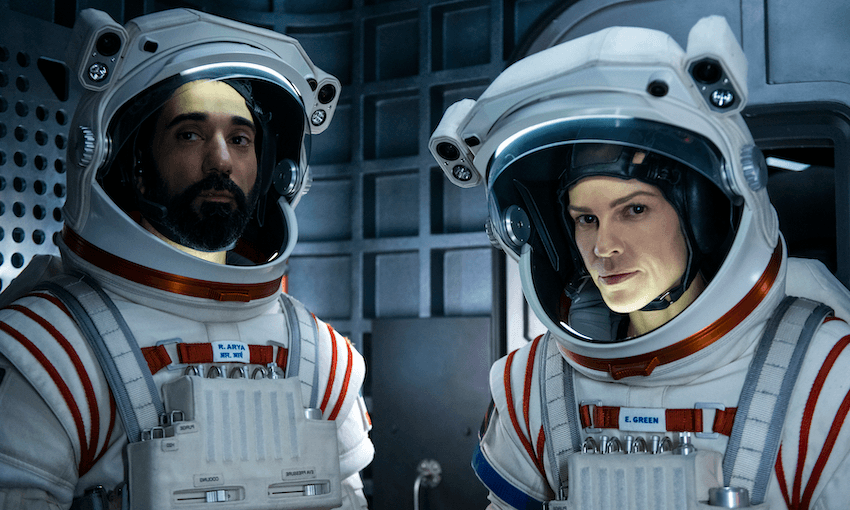

Away has a remarkable pedigree: it stars Hilary Swank and is executive-produced by Jason Katims (Friday Night Lights, Parenthood), Ed Zwick (My So-Called Life), and Matt Reeves (Felicity). It’s about humanity’s first mission to Mars, a mission with both crew and resources from several countries around the world, and all the expected stress that comes with that. But it’s also about the various interpersonal dramas of the astronauts on board, and how being on a three-year-long mission magnifies them. It’s another Katims show that lures you in with the straightforward concept and then surprises you with the fact that, yup, it’s actually all about the feelings.

Swank, perhaps the least fortunate double Oscar winner in history, does more for the show than it does for her. The same adjectives that are thrown around about every good Swank performance – so pretty much just her two Oscar-winning ones – apply here as well. She’s gritty, she’s tough, she’s no-nonsense. Even though Away often defies logic and sense for the convenience of drama, Swank does her best to make us believe Emma, the Mars mission commander. There’s a brilliant moment late in the third episode where Emma has to make a joke in order to win over one of her crew, and Swank makes it very clear that while the character is uncomfortable with humour as a concept, she knows it’s necessary to get back to business; we see every thought in the process play out on Swank’s face. So while Swank is doing good work here, she’s not so much working in the show, but around the massive holes the show has left for her; she turns a hollow set of ideas and plot points into a fleshed-out character.

The rest of the cast, including Josh Charles (The Good Wife) as Emma’s earthbound husband, are solid, and the actors playing the mission crew are especially compelling, but not even they can get past the show’s frustrating split focus. The show’s structure, which loosely focuses on a different member of the crew every episode, relies on flashback and cuts back to Earth so frequently that it’s easy to think that what’s going on in space is incidental, rather than monumental. While the inner lives of the astronauts aren’t uninteresting, and the episode that focuses on Chinese astronaut Lu’s struggle with her culture and her sexuality has some interesting moments, the endless psychodrama lessens the grip of the show’s core premise. Away never makes the first human mission to Mars as interesting as the many, many internal struggles of the astronauts (my lord, they are messed up, and they also mess up in so many ways that it makes you worry for the astronauting profession) and it suffers immensely for it.

But the biggest problem with Away is that it doesn’t make sense. Take Emma. In the first episode, after the mission’s launch, she attempts to go back to Earth after her husband is involved in an accident, and displays so many errors in leadership that she doesn’t seem fit to lead a mission to the supermarket, let alone Mars. Meanwhile, the people the astronauts have left behind on Earth often conveniently forget the deadly risks of the mission their loved ones are on (and so long as we’re talking about things that don’t make sense, Emma’s family is able to text and call her nearly constantly – in space). Nonsensical plot points don’t have to ruin a show. Audiences can forgive leaps of logic, but none of the elements of Away – including some pretty decent visual effects – are engaging enough to distract from the fact that it makes not one ounce of sense.

Away has a concept that could be both fascinating and emotionally fruitful: it’s a space drama where space just isn’t that much of a big deal. Unfortunately, it tries to be something bigger by equating the huge stakes of getting to Mars with the smaller, more internal stakes of the crew’s family drama, thereby diminishing the importance of both. This is the kind of territory that Jason Katims has worked in effectively in the past – Friday Night Lights is, at its core, a show about family, not football – but it feels stretched and forced here. No matter how hard Swank acts, it’s never believable that this astronaut would think that her daughter getting into a comparatively mild bike accident is on the same level as the first mission to Mars. If the show doesn’t think the mission is important enough to focus on, why should we?

You can watch the first season of Away on Netflix now.