Based on one of the most notorious murder cases in New Zealand history, Mistress, Mercy finds itself hamstrung by the limits of the doco-drama genre.

In 1989, Renee Chignell and Neville Walker were convicted of the murder of Peter Plumley-Walker. Police alleged they had thrown him into the Huka Falls after a bondage session with Chignell, who was aged 18 at the time. It took two retrials for a jury to be convinced that Plumley-Walker had actually died during the bondage session, accidentally, when Chignell was out of the room. The story was a media sensation, and 30 years later, we’ve got Mistress, Mercy, a doco-drama that combines recreations of the events with Chignell’s own words, which have not been heard until now.

There’s no question of the worthiness of Renee Chignell’s story. There’s no question that we all need a reminder about how our justice system and by proxy, our society, is rigged against women, and especially rigged against sex workers. When we see scenes of Chignell being mistreated by the police, by her boyfriend and by the court proceedings, it nudges something in you. This happened 30 years ago, but how much has actually changed? How much are the voices of the already marginalised being minimised and warped in the name of expedited justice?

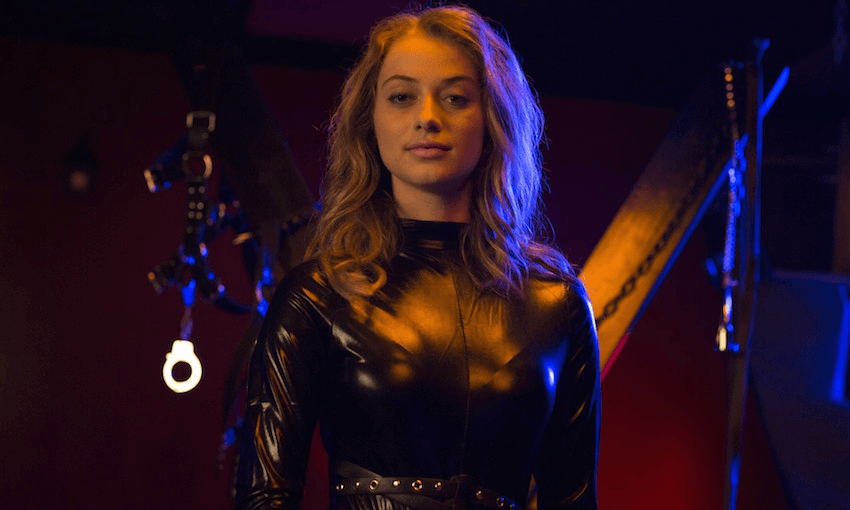

In some ways, there’s something quietly revolutionary about a story like this, which reframes Chignell’s story in her own words, in the Sunday Theatre slot. There is a luridness to the depiction of the story – especially the scenes in which Renee engages with clients – that feels very HBO, or what HBO was 20 years ago. It’s definitely not a story about Kate Sheppard, or Katherine Mansfield, or any number of women who lived very period-costume-drama lives that lend themselves well to these television events.

That Sunday Theatre slot is generally reserved for real-life TV movies which get huge ratings on their premiere, and then find their place on the media shelf afterwards. A lot of stories ripped from headlines through the years. Lots of stories worth telling, but not necessarily being told in the most revolutionary or even the most appropriate way.

Which is what brings me to Mistress, Mercy‘s one big problem. The doco-drama aspects play up the luridness of the case, particularly Chignell’s circumstances and work – it’s all moody noir lighting and dialogue that gets the maximum amount of exposition across with the maximum amount of drama. Often, it feels like the recreations aren’t trusting the story. The scene where Walker dies is a particular misstep: it’s all slow-motion, extreme close-ups and muffled screams. Chignell’s words are chilling enough on their own. Do we need the Lifetime movie theatrics around them?

And that’s where the entire piece turns in on itself. Is doco-drama really the best vehicle for Chignell’s story, or for this kind of real life true crime story at all? Over the past decade, we’ve seen a hunger for these true crime stories – and to see them examined at length and with as much depth as possible. Single cases are explored through podcast series or 13 episode shows; details are pored over by producers and audiences alike. Just look at at The Jinx, Serial, S-Town: there’s a real demand for this type of content.

But in 2018, doco-drama seems like such an antiquated way to present it. Recreations never have the same impact as fully-scripted drama, or actual archival footage – you’re seeing snippets of scenes and people rather than anything properly fleshed out.

It’s hard to give Chignell’s words and story the space they need when half of the two hours (including ads) are taken up with fictional recreations. While Mistress, Mercy includes a lot of Renee Chignell talking directly to the camera – and these parts are invariably the best part of the whole thing, because she’s a charismatic and articulate woman who has an incredible handle on what happened to her and why – it also includes a lot of dialogue recited by actors who are playing the idea of real people, rather than characters or anything close to those real people.

To Mistress, Mercy‘s credit, in terms of journalism it’s about as robust as you can get in two hours. It does a good job of balancing the actual facts of the story – the killing, the investigation, the courtroom proceedings – with Chignell’s interpretation of them. It doesn’t feel like we’re missing anything, necessarily, by telling this story in this way, even though Mistress, Mercy is weighted far more heavily towards the crime and the investigation, at the expense of what came later.

But it also doesn’t seem like we’re gaining anything from telling the story like this, other than Chignell’s own words, which are vital and necessary. It’s so rare that we’re actually given the opportunity to listen to how people dealt with injustice, especially women and especially sex workers.

But the recreations? They’re not vital, or necessary. Docu-drama is neither the best fictional treatment this story could be given – no story or performer is served well by skeletal scenes and generic dialogue – nor is it as immediate and powerful as a completely factual retelling. So why do it at all?