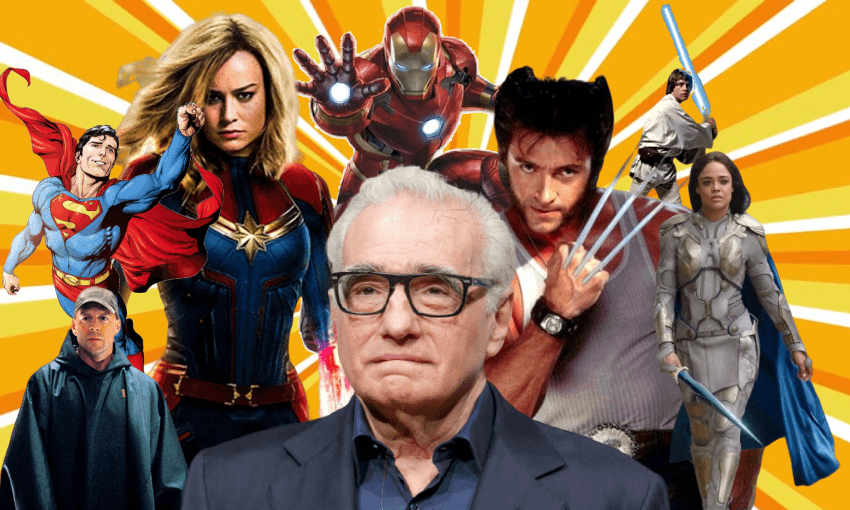

Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Ken Loach all have one thing in common: they don’t like superhero movies. But are they right? Are they heck. Josie Adams defends the existence of the world’s most money-hungry film genre.

There’s only one thing worse than a comic book nerd; a film nerd. Nerds of any kind can shove their four-eyed heads up their virgin asses, but the ones who study film are a particular kind of insufferable.

Once they become award-winning directors, we figure they’ve contributed enough to the imagination base to allow a bit of pretentiousness. Sadly for our champions of authentic cinema, your stock-standard superhero nerds didn’t get that memo.

Martin Scorsese (The Departed, Goodfellas) said something a couple of weeks ago about superhero movies that incurred the wrath of cosplayers across the globe:

“Right now the theatres seem to be mainly supporting the theme park, amusement park, comic book films. They’re taking over the theaters. I think they can have those films; it’s fine. It’s just that that shouldn’t become what our young people believe is cinema… It’s not my kind of thing, it simply is not. It’s creating another kind of audience that thinks cinema is that.”

He was paraphrased by every news outlet as saying “the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) isn’t cinema,” which is probably a fair representation of his views. He believes cinema is work that shows “human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being”. Work like Scorsese’s, about organised crime and characters haunted by their own violent pasts – oh, woah, is that Captain America: The Winter Soldier?

In fairness to Scorsese, he’s right about the theme parks. Marvel is owned by Disney, and DC Comics has a pop up at Six Flags in the U.S. That’s Hollywood, baby! Scorsese’s stacking coin just like the rest of them. You’re all rich as sin and rolling in the capitalistic filth of broad-appeal cinema. Yeah, I said it: The Wolf of Wall Street isn’t a niche artistic masterpiece.

However, unlike stand-alone portraits of antiheroes with massive eye bags, the Marvel machine supports thousands on thousands of extras and film crew, many of whom return for each subsequent film and have a sense of security in an industry that, outside of the comic book genre, is pretty unstable.

Scorsese believes there should be more support for narrative films like his latest, The Irishman, coming to Netflix this November. The Irishman could be Netflix’s best shot at an Oscar, and Ray Romano’s best chance for critical redemption since Ice Age 5: Collision Course. Narrative film is more valuable to Scorsese because he’s portraying historic moments:

“How are they going to know about World War II? How are they going to know about Vietnam? What do they think of Afghanistan? What do they think of all of this? They’re perceiving it in bits and pieces. There seems to be no continuity of history.”

Batman director Christopher Nolan’s World War II film Dunkirk received three Oscars, grossed US $527.3 million worldwide, and is the only film about war I’ve ever actually enjoyed. Idiot savant Zach Snyder’s Watchmen did more for my awareness of U.S. forces’ misdeeds in Vietnam than anything Apocalypse Now portrayed (remember, I am a dumb millennial).

I mention Nolan’s work outside of the superhero genre because that’s a key part of what superhero movies do: they give auteur directors the opportunity to access bigger budgets. MCU directors include:

Jon Favreau, who was a pop-indie film actor and directed Zathura: A Space Adventure before taking the reins on spearhead Marvel movie Iron Man.

Taika Waititi, our favourite anti-hate satirist, who went from working with a US $1.6 million budget on What We Do in the Shadows to directing Thor: Ragnarok, which had a budget of US $180 million. He’s also now friends with Jeff Goldblum, which is the greatest achievement of any New Zealander.

Joss Whedon was straight from TV (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly). The only film he’d directed before The Avengers and Avengers: Age of Ultron was Serenity, which was just Firefly but two hours long (it’s good).

James Gunn’s directorial debut was Slither, a low-budget horror-comedy starring Nathan Fillion and Elizabeth Banks about a slimy alien invasion. He went on to make Guardians of the Galaxy, and now they’re letting him re-film The Suicide Squad so that it’s actually good.

Ryan Coogler made Fruitvale Station, based on the very real and tragic Oakland shooting of Oscar Grant, and then re-used Michael B. Jordan when he was chosen to direct Black Panther. The film won three Oscars, and now Coogler’s being eyed to direct what will be the greatest film of this generation: Space Jam 2.

Outside of allowing genuinely creative directors to get their hands on project funding and providing incomes to hundreds of thousands of workers in an increasingly unviable economy, what good are superhero movies? Do they have artistic merit? Yes!

The hero is a cultural archetype, one that’s been in stories since the beginning of time. Hercules was a hero. Beowulf, Luke Skywalker, and Harry Potter are all heroes. They are burdened with purpose and gifted with some kind of power: destiny, midichlorians, adamantium claws, whatever.

The key to understanding the appeal of the hero – and superhero movies – is that the hero archetype is an immature one. It represents adolescence, a burgeoning manhood. That’s why George Lucas followed Luke, then switched to Anakin, and now Rey. It’s why Iron Man is dead. Once your hero reaches their limitations or serves their purpose, they become either dead or the wise old man in the story.

This means two things. First, that superhero stories – in ballads, novels, comic books, and movies – are timeless. Second, that superhero stories appeal primarily to kids. Ten-year-olds loved Superman in the 1950s, and they can’t get enough of Captain Marvel now. They see someone realising their power, using it for good, and being respected for their internal strength as much as their gifts. It can be difficult for adults to understand the impact of this.

During last year’s Avengers: Infinity War there was a shot I hated. It’s the final battle: everyone versus Thanos. “I don’t know how you’re gonna get through all that,” says Spiderman, looking out at a very hectic battlefield. Captain Marvel smirks. “Don’t worry.” Scarlet Witch, Pepper Potts and Valkyrie land with a thump next to her. Mantis, Shuri and Okoye walk in from off-screen. “She’s got help,” says Okoye. The Wasp and Gamora are also there. All the ladies are in this together. A bunch of badasses.

Watching it as a 26-year-old, I found this scene to be a pretty blatant piece of pandering. It was designed for PR, I griped to my little sister, and she stopped me. “That scene wasn’t for you,” she said. “It was for 12-year-old girls.”

It’s not for me, and it’s not for Scorsese, and that’s the point.