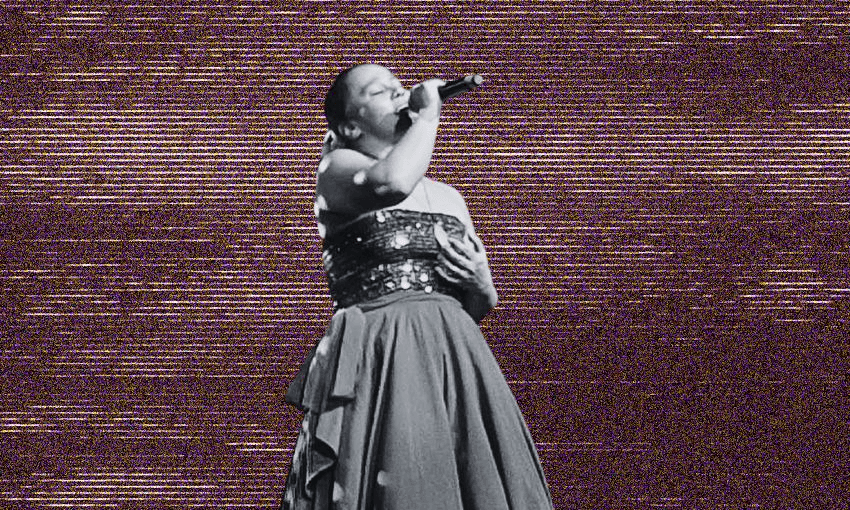

Micro-aggressions and a difficult history with te reo Māori is why last year’s Gold Guitar winner says she won’t return to the ceremony or its homeland of Gore.

Country singer and 2024 Gold Guitar main prize winner Amy Maynard has vowed publicly to never return to the ceremony and its host town of Gore, after facing what she believes were racially-charged micro-aggressions. She said the ceremony has a history of failing to recognise te reo Māori, and hopes her experience could push the Gold Guitar organisers to create a safer environment for Māori performers and punters. But the organisers say they’d rather sort out their differences in private.

Aotearoa’s premier country music awards, the Gold Guitar Awards, have been held every year since 1974 (excluding 2020) in Gore, as the last hurrah in the Tussock Country Music Festival schedule. Its honourees include the likes of Tami Neilson and Kaylee Bell, and in 2024, Maynard picked up the ceremony’s senior award.

Maynard told The Spinoff she had spent most of the festival last year – her first time at the ceremony – keeping to herself, and focusing on performing in several spots across the awards circuit.

Returning this year as a one-off performer and attendee, Maynard says the environment at the awards was “really disheartening”. She said that in her experience, the awards’ security were more likely to reprimand “brown faces” for actions such as singing, dancing or talking during performances. Her 16-year-old son, dressed in baggy clothing, was also stopped multiple times and questioned about why he was at the awards.

It was not just staff, but attendees that Maynard said made the awards feel unwelcoming. While one singer performed a reo Māori waiata, Maynard said an older Pākehā couple made disparaging comments about the choice of song.

When The Spinoff called the Gold Guitar office, convener Phillip Geary answered. “I don’t want to comment in a public forum,” Geary replied, when asked about Maynard’s experience.

In 2012, a Gore District Council employee left their job after criticising the Gold Guitar Awards. She had competed in the Gold Guitar Young Ambassador Awards, and wrote on Facebook that she “kicked ass at everything and then didn’t win, go figure … I think I was too brown for them bro”. At the time, Geary said he didn’t believe Green needed to resign. “With the way social media is these days, we’ve got to expect stuff like this. We’re not overly concerned about it.”

“As a Māori woman in this industry, it’s hard when you’re constantly fighting this uphill battle,” Maynard told The Spinoff. ”These people have built this idea of what you’re going to be in their minds”.

Maynard also criticised the awards’ policy that bars anyone other than the slated performer from appearing onstage. Maynard requested her mother and daughter sing with her, as “you should be allowed to provide and perform the show that you would like to put on for people … for me, that includes highlighting and showcasing my family, because whakawhanaungatanga is always going to be something I’m huge about”. The response from the awards was that it would “set a bad precedent”.

The rule affected another act, Sharon Russell and Lesley Nia Nia, who had won the previous year’s classic award. Russell had travelled to the ceremony without Nia Nia, who could not attend for personal reasons, but with her grandson as a replacement. Maynard claims Russell was told she couldn’t perform and her act was replaced.

Maynard shared these experiences in a long social media post, which The Spinoff understands the Gold Guitar organisers have seen. Television personality Mike Puru, who MC’d the event, left a message of support on Maynard’s post promising to take her comments to the ceremony’s board. “I’m so sorry that happened – I had no idea … I’m saddened by all of that, especially being a Māori fella from Gore,” Puru wrote. “I know what you mean.”

In the last year, against the backdrop of the Treaty principles bill and Toitū Te Tiriti hīkoi, Maynard said she had noticed anti-Māori rhetoric had become more “vocal”. The singer, who lives in Hamilton, said she doesn’t feel comfortable returning to Gore or to the Gold Guitar Awards.

“I hope this opens a conversation for them.”