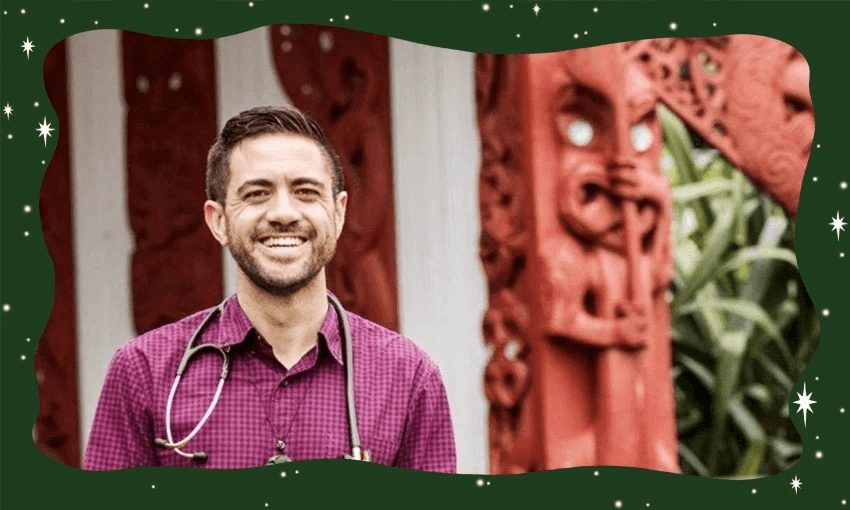

As a doctor, medical educator and iwi health advocate, Mataroria Lyndon has seen how cultural safety transforms health outcomes. The government’s proposal to remove cultural requirements from workforce regulation, he writes, risks undoing decades of progress and putting lives at risk.

As a doctor and medical educator, I teach clinicians about what it means to provide care that is not just clinically competent but also culturally safe.

Every day, I see the power of cultural safety to strengthen relationships, improve health outcomes, and lead to better care. That’s why the Ministry of Health’s recent public consultation to remove cultural requirements from health workforce regulation is not just misguided – it has the potential to harm patients.

The Ministry’s Putting Patients First consultation includes a question that frames cultural safety as something separate from – even opposed to – clinical safety: “Do you agree that regulators should focus on factors beyond clinical safety, for example mandating cultural requirements, or should regulators focus solely on ensuring that the most qualified professional is providing care for the patient?”

This question promotes a false dichotomy. Cultural and clinical safety are not competing priorities – they go hand in hand. You cannot be clinically safe without being culturally safe.

I say this as a Māori doctor, as someone who trains clinicians in cultural safety, and as a member of Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board, which represents 114,000 whānau Māori across the Tainui waka region.

We have formally opposed any move to weaken cultural regulation. Because to do so would be irresponsible, deepen inequities, and be a massive step backwards for healthcare in Aotearoa.

Cultural safety is not an optional extra. It is core to best practice and has been embedded by many professional bodies, universities and regulators over the last 30 years.

It applies to ethnicity and many aspects of identity – including gender, disability, sexuality or religion – that shape how a patient experiences care. It helps clinicians build trust, listen better, communicate more effectively and deliver care that patients can actually engage with. It empowers patients in their healthcare and seeks to address inequities within the health system.

Healthcare professionals are bewildered. This survey was not requested by clinicians or professional bodies and threatens to set our health system back decades.

Take, for example, the section that criticises some professions for “prioritising cultural requirements” like an understanding of tikanga Māori in hiring, then suggests an alternative model of “patient-centred regulation” that appears to exclude cultural factors altogether.

It implies that cultural and clinical competence are in competition, rather than mutually reinforcing.

In reality, cultural safety is central to clinical excellence. It’s about ensuring that patients feel heard and respected. When patients do not feel safe – culturally or otherwise – they may avoid care, omit sharing crucial health information with clinicians, or disengage from treatment altogether. That can put lives at risk.

The Council for Medical Colleges, Te ORA (Māori Medical Practitioners Association), the Royal Australasian College of Physicians and the New Zealand Medical Council affirm that cultural safety benefits all patients and communities. It gives patients the power to comment on practices, be involved in decision-making about their care, and contribute to achieving positive health outcomes and experiences.

It is also an obligation under te Tiriti o Waitangi principles in health to provide culturally appropriate care, a central pillar of the Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022 to provide services that are culturally safe and responsive to people’s needs, and an established priority in Te Pae Tata – the government’s own interim health plan.

In September last year, Te Tiratū Iwi Māori Partnership Board submitted both a priorities report and a community health plan to senior government officials, calling for high-quality, community-led, culturally safe care across our region.

These are not niche views – they reflect what communities want, what clinicians are trained to provide, and what research has highlighted is essential for health equity and improving quality of care.

So why are we entertaining a proposal to weaken this standard?

If this consultation is any indication, it appears less about putting patients first and more about undermining decades of progress toward health equity.

It sends a message to Māori, Pacific, takatāpui (LGBTQI+), tāngata whaikaha (disabled whānau) and others who have historically faced discrimination and marginalisation in healthcare that their safety doesn’t count. That is unacceptable.

Culturally unsafe care is unsafe clinical care. We cannot pretend otherwise.

This is not the time to retreat. It’s time to double down on our commitment to health equity and building a health system where every person – no matter their identity – receives health care that is competent, compassionate, and culturally safe.

Aotearoa deserves nothing less.