For many iwi, the Māori new year was never marked by Matariki – but by Puanga, a brighter star that rises first in winter. As knowledge is reclaimed and wānanga held across the country, Puanga is once again taking its place in the sky.

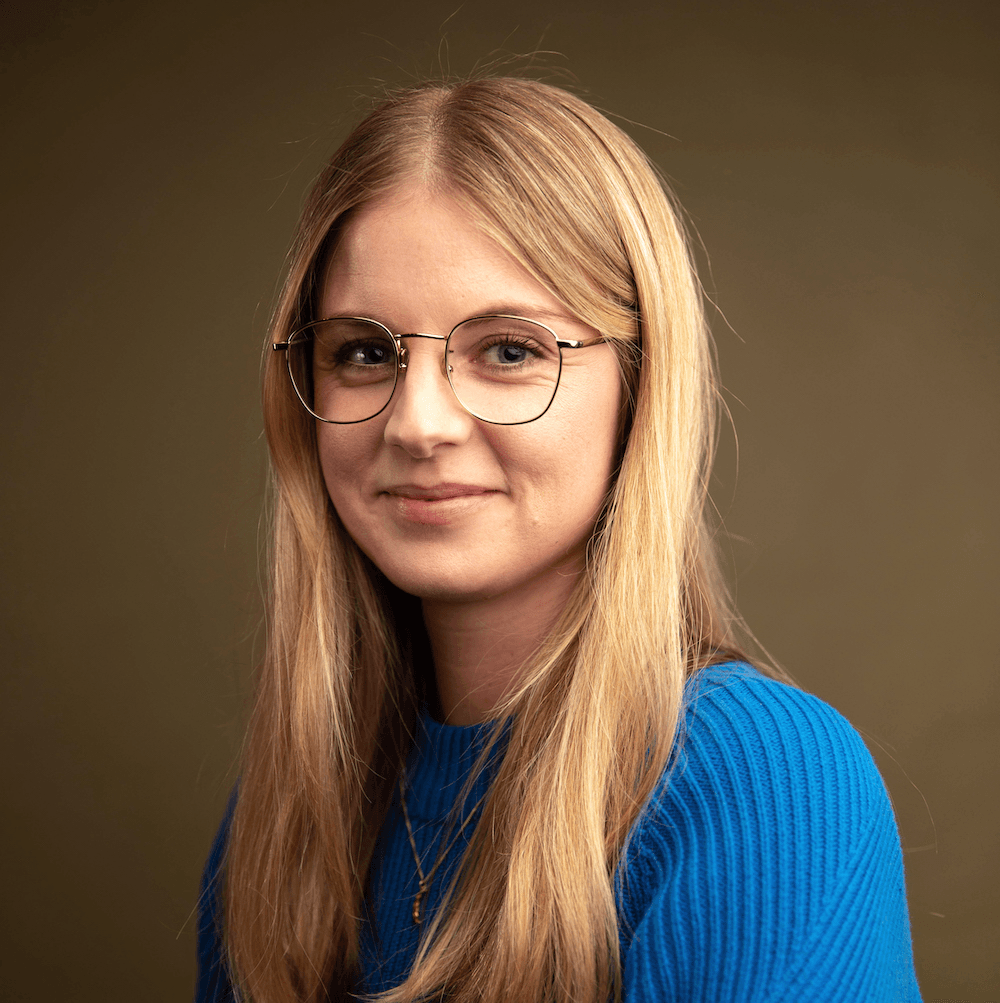

I didn’t grow up knowing anything about the Māori new year. In fact, the extent of my knowledge about the maramataka Māori was Bill Hohepa’s Māori fishing calendar, which my uncles and dad swore by when planning any fishing trips. When awareness of Matariki started ramping up around the country about a decade ago, I thought: “Cool, Matariki is our Māori new year.”

While I had heard about other stars besides Matariki being significant to iwi, it wasn’t until 2022 that I became fully aware of the significance of Puanga. A group of maramataka experts from Te Tai Tokerau, including the likes of Pouroto Ngaropō and Rereata Makiha, were hosting a series of Matariki-Puanga wānanga around the north. I ended up attending one at Korou Kore Marae in Ahipara, where we were taught about the significance of Puanga to our people in Te Hiku-o-te-ika.

For us in the far north, particularly along the west coast, Puanga, known as Rigel in western astronomy, is the more easily seen star rising in the sky, as opposed to the Matariki cluster. The same is true for much of the west coast of our country and even in Te Waipounamu. In these areas, Puanga was more often the star we used to mark the time of winter.

Now into our fourth official Matariki public holiday, many iwi are beginning to reclaim their knowledge of Puanga too. It’s not a case of either or – as most of these iwi still acknowledge Matariki too – but rather a reclamation of iwi and hapū-specific mātauranga that celebrates and honours Puanga. Many of the practices are the same: coming together with whānau, reflecting on the year that has passed, sharing kai, and preparing the māra for the warmer months ahead.

Sadly, a lot of traditional mātauranga about the maramataka and whetū like Puanga was actively suppressed through colonisation and missionary influence, including the marginalisation of tohunga and seasonal observations. Māori traditionally used the sun, moon and seasons to measure time, reflecting the natural rhythms of the taiao. There were signs in nature about when the best time was for certain activities, like kina being fat when the pōhutukawa bloom, or snapper spawning on a particular moon, or tuna migrating at a certain time.

With colonisation came a new system of timekeeping – the Gregorian calendar. In 1868, New Zealand became the first country to have a nationwide time decided by the government for everyone to follow. There were 24 hours in a day and 365 days in a year. Laws like the Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 aimed to repress mātauranga Māori in favour of western knowledge, leading to the loss of many traditional practices.

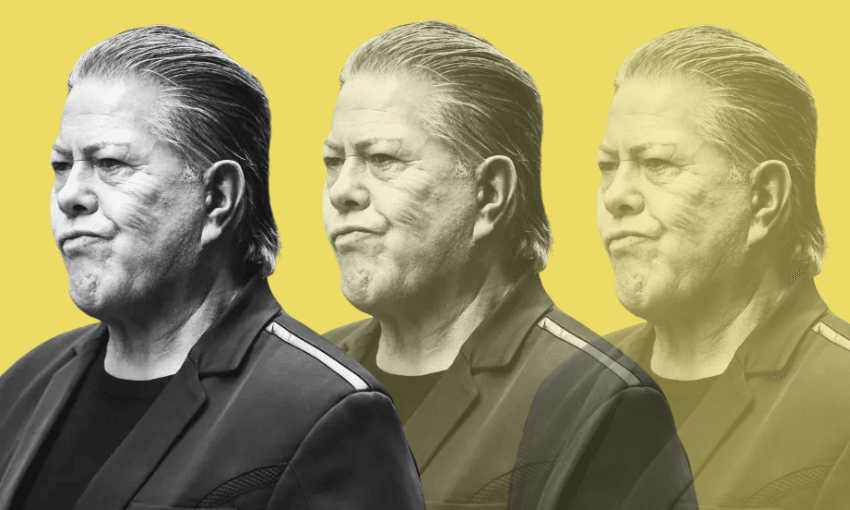

While the acknowledgment of Matariki and Puanga remained a practice for some Māori, many simply adopted the western practice of celebrating the new year on December 31. That is, until the renaissance of Matariki began under the guidance of Rangi Mātāmua in the early 2000s. By 2021, a bill was being introduced to parliament to make Matariki a public holiday. However, whether it was geographic visibility, pan-Māori education or government framing, Matariki became the better-known star cluster while regional stars like Puanga were overshadowed. But with Puanga being the star of this Matariki holiday, its significance is finally beginning to be recognised by the wider collective.

In Whanganui, Ngāti Rangi and other iwi of the awa have long observed Puanga, holding dawn ceremonies at marae and atop maunga to mark its rising. In Taranaki, Puanga has always been the focus – not as a substitute for Matariki, but as their own celestial marker of transition and renewal. And across Te Waipounamu, where Matariki is less visible due to the landscape and climate, iwi such as Ngāi Tahu are increasingly reclaiming their historic ties to Puaka – the southern form of Puanga – as part of broader maramataka revival efforts.

These aren’t just ceremonial acts either. Reclaiming Puanga is a reclamation of time itself – of the rhythms our tūpuna lived by before the Gregorian calendar was imposed. It’s also a reaffirmation that mātauranga Māori is not a monolith. For all the value of creating a unifying public holiday to celebrate Matariki, the true beauty lies in the diversity: the way our many iwi looked to different stars, at different times, from different parts of the motu, guided by the unique relationships they held with the taiao around them.

While Matariki as a holiday has helped foster widespread awareness and celebration, some communities are now gently challenging the narrative that Matariki is the only or primary whetū of the Māori new year. The reclamation of Puanga – and the space being made for it in classrooms, on marae and in public-facing kaupapa – reminds us that Māori ways of marking time are inherently place-based, whakapapa-based, and deeply rooted in the local knowledge of each hapū.

As Makiha has alluded to, we don’t just read the stars – we read the land, the tides, the birds, the trees and the wind. Puanga’s reappearance in the pre-dawn winter sky is just one tohu among many. It signals a time of pause, of remembering those who have passed and of planting seeds – literal and metaphorical – for what comes next.

At the wānanga I attended in Ahipara, we rose in the dark to karakia as Puanga climbed into the horizon, just above the headlands. The cold bit at our ears, and a light mist clung to the hills. But in that moment, standing among kaumātua, mokopuna and kaiako, there was a feeling that something ancient was being remembered – not learned, but recalled, from deep within our bones.

Puanga doesn’t replace Matariki. It simply reminds us that our stories are richer than a single version. That our skies are full of stars. And that in reclaiming our own whetū, we reclaim our right to see the world in our own way.

The Spinoff has partnered with Mānawatia a Matariki to platform two short videos profiling whānau who honour Puanga. Check them out @thespinofftv.