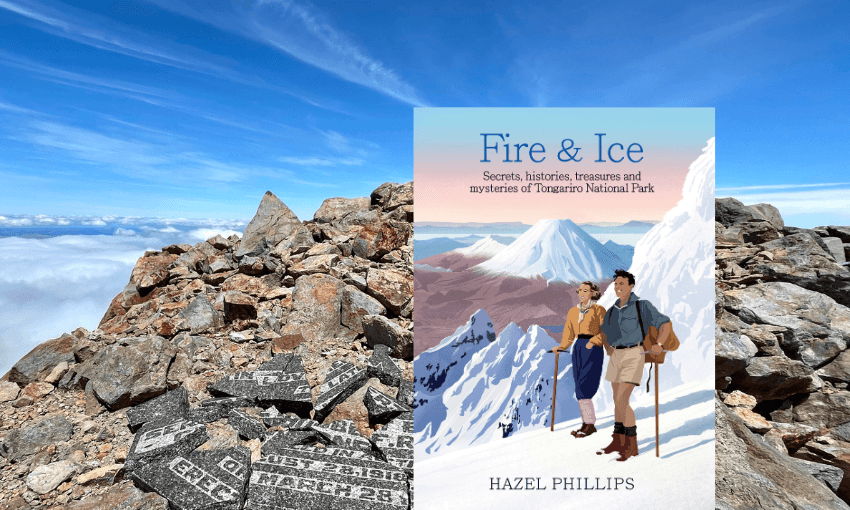

An edited excerpt from Hazel Phillips’ book, Fire & Ice: Secrets, histories, treasures and mysteries of Tongariro National Park.

When we ascended Girdlestone Peak in 2023, the skies above Ruapehu’s massif stretched clear and starkly blue above us. Sun reflected off the volcanic rocks around us as we sweltered up the black hill. When a group of mountaineers ascended Girdlestone over a century earlier, they needed three attempts to carry out their mission. Clouds surrounded them, their clothes froze stiff, and the misty wind picked up rocks and fired them at the party. You’d almost think the mountain didn’t want them there.

We navigated blocky sections of rock, looking for a way to get onto the ice of the Mangaehuehu Glacier. I stopped to breathe.

“What pseudonym do you want in my book?” I yelled out.

“Henry,” he called back immediately. Then turned and laughed. “I dunno, call me whatever you want.”

“Henry” stuck. I didn’t know any Henrys in real life, so that helped.

The day I first crossed paths with Henry up on Ruapehu he quietly told me what he’d done: “That plaque on Girdlestone, I went up and smashed it.” It took many blows to smash the granite tablet, pinned as it was to the large, smooth face of the rock by its four thick copper pins. Then he cast the shattered pieces around the peak.

A group went up Girdlestone about a year later and discovered the broken plaque, then spent an hour picking up some of the pieces.

Later, after discovering that the plaque had been jigsawed back together, Henry went back in my company to finish the job. He wanted to chuck the broken tablet off the peak again, but I felt that would convert it from history into rubbish.

At the summit, I sat on a nearby rock, staying well clear as Henry attempted to remove the copper pins — valves from an old car engine. They protruded about five centimetres from the rock. A scar on the landscape, on the mountain Ngāti Rangi call Koro — their grandfather, ancestor and the source of their identity.

“You write in there that the fulla who did this is as white as they come,” he said. “Who the fuck are you to put a plaque up here? Go and plant a fucking tree, a tōtara or a rātā or something that’s going to be around for ages. Plant it in your backyard and go sit under it, for fuck’s sake.”

Soon enough the first valve popped off. I picked it up to examine it, surprised at its heft. The oxidised green had been sheared off by the hammer, revealing bright copper in the spots where it had been hit, and on the inside stem, after it had been protected from the elements for more than 100 years.

“From back in the day when they made things to last,” Henry observed.

Huge bugs were crawling over the summit, overly friendly in their approach, and whenever the breeze dropped, clouds of sandflies plagued us. A bug got in Henry’s way. We were, after all, disturbing their home, crusading invaders in their peaceful environment.

“Look out, bug, you’ll wear it,” Henry warned as he brandished the hammer.

The last valve popped off. Henry straightened up, released the hammer and picked up his water bottle. He gazed around, then bowed his head to the scarred rock face. “Sorry, mate, couldn’t get it all out this trip.”

The valves had refused to come out cleanly, so the stems were still embedded inside the rock. Four round scars told the tale, each with a broken piece of copper stem shining brightly. Hopefully they’d fade over time.

We took a final look at the last of the scenery below that was still visible from the summit.

“Koro’s let us up today,” Henry observed.

A thin wisp of mist flicked through from the south, between me and Henry. Koro had let us up, but now it was time to go.

Hugh Girdlestone, bastion of climbing, mountain enthusiast and surveyor of Tongariro National Park, a man who spent his days ascending peaks and his nights camped beneath stars on the rocky volcanic slopes of the maunga, a man stout of stature and blessed at times with a bushy handlebar moustache, did not die on the mountains of the central plateau he loved so much; he did not come to grief crossing a swift river of glacier melt, nor did he perish from speeding ballistics ejected violently from Ruapehu’s crater; no — Hugh Girdlestone died from shrapnel flying across a battlefield, piercing his tent and then his flesh. Girdie, they called him affectionately. Girdie died not on the mountains he adored, but at the hands of the nation’s enemy, in wartime, in his sleep.

His friends decided to erect a memorial to him and deemed a granite tablet the most suitable to withstand the ‘severe climatic conditions’ up high. They organised a party to fix the tablet in place, which would be done — so they thought — no later than Easter that year, 1921. Their confidence led them to engrave it with the intended date: 23 March 1921. The mountain had other ideas; Ruapehu wouldn’t let them up there until 12 March the next year, after two foiled attempts.

The plaque and copper valves sat in my living room for a while. It wasn’t all there; we’d only managed to find about half of it, and the rest was lost forever around and underneath the peak. The pieces felt heavy in my hand, as did the valves — weighted not just by their innate heft but also by the heaviness of what we’d just done. A couple of pieces were distinctly pointy and resembled the shape of Girdlestone itself. They were dirty, but once dusted off they looked as shiny as if the tablet had been manufactured last week.

Eventually I packed it all away in a box and slid it to the back of a dark cupboard, to be addressed and dealt with later. I didn’t want to just chuck it out — it was history, after all — but I’d been an accessory to removing it from the backcountry. There had been a reason, even if I hadn’t yet identified that reason precisely to myself.

I had a chat with a cultural rep from Ngāti Rangi and told them the plaque had been intentionally smashed. Their thoughts were that it was best to “leave nature to do what it needs to do”.

The day we went up Girdlestone I came away covered in finely milled rock dust and ochre-coloured dirt, so I walked to my favourite mountain swimming hole, a jewel-green spot surrounded by smooth rocks made hot by the summer sun, with a view up to Girdlestone. I dunked myself repeatedly in the water, full-body immersion in snow melt, some of which had probably trickled down from the glacier I’d been on earlier that day. I felt cleansed.

Words I’d read by Ngāti Rangi leader Che Wilson in an article echoed back to me from the mountain: that there are different interpretations of the notion of “tapu” and associated practices. “You went at a certain time of year, and did karakia to invoke your ability to see the unseen,” Wilson wrote. “There are key guardians in the mountains that we talk to to ask permission to go up, and also to give respect to them as they look after those places.”

As a Pākehā, these were cultural practices I didn’t have access to, but we had some things in common. Wilson pointed out the key to a relationship with Koro Ruapehu was to enjoy him, but respect him, and I felt that. “Irrespective of culture, the lofty peaks are a recognition of that which is special and unseen,” he wrote. “Going to those lofty places is all about being inspired and given a spiritual recharge.”

In March 1924, two years after the plaque was installed, a small party climbed Girdlestone to check on the state of the memorial tablet. The Evening Post reported: “Despite the powerful disintegrating forces which are continually acting against this precipitous pinnacle, the monument displays no sign of deterioration and the party are now of the opinion that its permanency is now assured.”

Fire & Ice: Secrets, histories, treasures and mysteries of Tongariro National Park by Hazel Phillips ($50, Massey University Press) is available to purchase from Unity Books.