There’s a unique network of people and organisations behind the Auckland art scene. Naomii Seah spoke to three of them to understand their mahi.

Walking through the streets of Tāmaki Makaurau, you’re never short of interesting art to look at. The city is home to macro pieces like The Women’s Suffrage mural at Te Hā o Hine place, and the iconic Boy Walking in Potters Park; as well as smaller installations like Thief and Twist, the bronze statues on Karangahape Road. Then there’s the more transient works of our city, like the Yarn for Pride project in February this year, which saw the bike parking on Karangahape Road adorned with colourful scarves in honour of Auckland Pride.

Artworks like these enrich our experience of the city and bring communities together, as well as being quite simply delightful. Even so, it’s getting harder for artists to create and produce work. Inflation, a cost-of-living crisis, and recent funding cuts have made art, and art-making, less accessible. Despite this grim outlook, some organisations, like the 21 local boards of Auckland Council, remain key supporters of arts and culture here. They help fund and manage many dedicated arts spaces and organisations across the city. The Spinoff spoke with three of these organisations about how they’re keeping our arts scene alive and vibrant.

Siobhan Connelly, Studio One Toi Tū

Studio One Toi Tū cuts an imposing figure on the corner of Ponsonby and Karangahape Road. Once a police station, it’s now an arts facility helmed by the Waitematā local board. The building’s strong, square silhouette and late Victorian brick facade can be intimidating at first. But this initial impression is tempered by the artwork proudly displayed in the windows. Acrylic “paint” drips from the upper windows, oozing art onto the street and the community beyond.

Inside you’ll find art exhibitions and workshops, maker spaces and studios. Studio One Toi Tū aims to keep their offerings free or low cost to ensure everyone in the community can access arts and art spaces. Workshops here offer a chance to explore a wide range of mediums – from ceramics to print-making, oil-painting and more. On-site studios and spaces can also be hired for events and pop-up exhibitions. This ensures the space remains responsive and reactive to current events.

Supporting the local arts scene is the core of the Studio One Toi Tū kaupapa, says manager Siobhan Connelly. The team are all arts practitioners themselves, and they aim to offer wrap around support for new and emerging artists. Downstairs, by the front door, four gallery spaces provide an opportunity for new and emerging artists to display their work. The exhibits are programmed a year in advance, with 30 to 40 slots available each year.

“We often talk of the story of someone coming through Studio One Toi Tū,” says Connelly. “There are people who have come to an exhibition, found out about the space, taken one of our courses, upskilled, then started doing markets, then applied for an exhibition. There’s a real opportunity to nourish people starting on their arts journey. And that really fills our cup.”

“We talk about people coming here and doing their ‘firsts’ – teaching their first class, holding their first exhibition, having their first studio. These are all important steps to being a member of the creative sector.”

Jermaine Reihana, Kākano Youth Arts

Kākano Youth Arts Collective is a programme for vulnerable rangatahi and is run out of Corban Estate Arts Centre – a West Auckland arts precinct based on the historic grounds of the former Corban Estate Winery.

Three days a week, Kākano welcomes 18 young people between the ages of 12 and 21 to the ground-floor room of the estate. It’s covered in colourful graffiti and paint splatters and is full of art supplies. Here, the participants are given the opportunity to develop an arts practice with experienced arts tutors. Jermaine Reihana is one of these tutors. He’s been with the programme since 2015, following a stint as the resident artist at the estate.

“Kākano means ‘the seed’. All we do as tutors and as a whānau is to pour as much tautoko support onto that seed and help it to grow. That’s how each of our rangatahi develops their own art practice.”

The programme is not run like a classroom, Reihana stresses. That doesn’t work for these rangatahi, who have mostly disengaged with mainstream education. Instead, each young person is given individual support, which extends not just through developing an arts practice, but to their wider lives. Kākano employs an in-house youth support coordinator, Sarah Candler, who helps young people navigate government systems and more.

“Our rangatahi rely on us a lot because they trust us. They’re able to approach us with what happens in their lives and we can navigate that alongside them.”

Reihana says the programme not only builds skills and self-esteem but gives young people work experience. The collective sells works at exhibitions every year and has made work for clients including Google, KiwiRail, Auckland Transport, local boards and council. When artworks produced by the collective are sold, 80 percent of the proceeds go back into the programme.

Kākano Youth Arts Collective has a variety of sponsors, including Henderson-Massey Local Board, who were instrumental in setting up the programme in 2013, when it was piloted by director Mandy Patmore.

“We wouldn’t be able to do what we do without the backing of Henderson-Massey local board,” says Reihana. “They’ve helped tautoko and support a lot of our external projects. If you see public artwork in the area, nine times out of 10 we’ve had something to do with it.”

Though the alumni at Kākano Youth Arts Collective never truly leave, Reihana says one of the programme’s biggest achievements is helping young people transition to further training or employment. The collective has a strong partnership with the Unitech School of Art and Design, and many young people go on to pursue Foundation, Certificate or Bachelor level qualifications there. Other Kākano alumni have gone on to Ama Training Group’s animation programme and have become animators. Others still have found their way into the film industry post Kākano.

“We’re not a course where young people come to us for six months and then get handed off. We’re a whānau here, no one leaves here without a plan.”

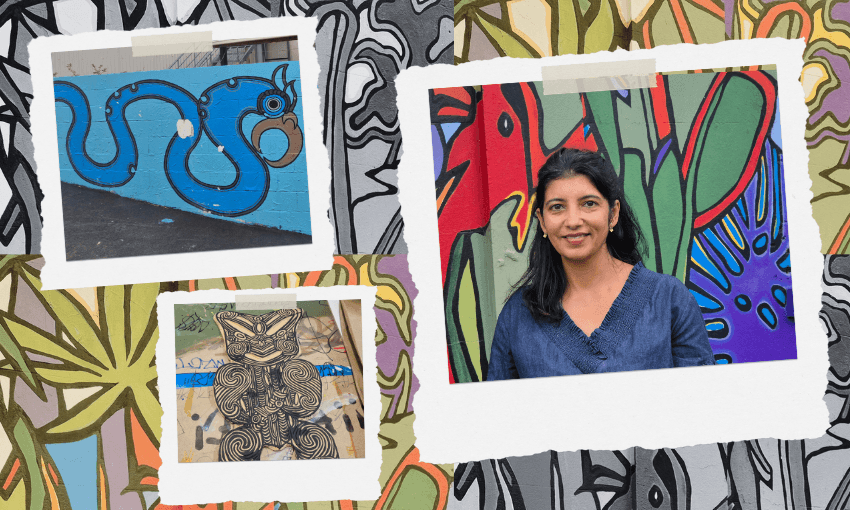

Shona Dey, Albert-Eden Arts Broker

Shona Dey is a familiar face at Frasers Cafe, located at the iconic Mt Eden intersection. Dey is the arts broker for Albert-Eden Neighbourhood Arts. Funded by the Albert-Eden Local Board, this organisation supports and promotes community-led arts and cultural activities across the two neighbourhoods. They collaborate with local artists, event organisers and creative organisations to bring ideas to life with funding, advice, marketing help and more.

Dey describes her role as an arts broker succinctly: “I’m a connector between community, arts practitioners, the local board and arts staff at Auckland Council. With local board funding, I help curate and deliver a programme of arts within the community informed by local happenings and the local environment.”

It’s a role that sees Dey out and about in the community most days, grabbing coffees and teas with people. Albert-Eden Neighbourhood Arts aims to keep barriers to entry low, and Dey often acts as a mentor and guide to newer arts practitioners who apply. Her typical day might include liaising with practitioners, helping with post-project reports, connecting artists to venues or other resources, or attending and facilitating community events. Dey says that her role and the model of arts delivery in Albert-Eden is unique. There’s no dedicated space or location beyond the Albert-Eden area itself. But the ephemeral nature of the model has its own benefits.

“It’s a very efficient model. It’s cost effective, and it’s agile,” says Dey. “We’re able to respond to community needs very quickly. We’re able to deliver projects in small, big and micro ways to where they’re needed most.”

Some projects Dey has helped to facilitate include a self-published children’s book written by a local postman, Mike Paterson, about the dogs he encounters on his post run. The launch was hosted at the local Time Out bookstore, and the initial print run sold out. Another is a photographic project by Sara Tautuku Orme, photographing local mana whenua, mātāwaka, kaumātua and kuia in Albert-Eden. Other projects have included theatrical, experiential arts projects aimed at activating the town centres, and increasing community cohesion and wellbeing. Arts projects can be microscale or larger in scope, with Dey trying to strike a balance. She says that the value of the arts is sometimes intangible, but the flow on effects of creating and seeing art are valuable.

“I think art is one of the pillars of mental health. It helps people feel safe in their community and like they belong. It’s such an important way people communicate to others. The arts is also an important economic developer and enabler for this area, with impacts well beyond the initial programme.

“That’s what I love about facilitating art in this role – it’s never really over.”