They’re both young, female, progressive leaders whose career trajectories are intertwined with Andrew Little. But their strengths, weaknesses, governing style and political legacies couldn’t be more different.

Windbag is The Spinoff’s Wellington issues column, written by Wellington editor Joel MacManus. Subscribe to the Windbag newsletter to receive columns early.

It was July 2017, less than two months out from the general election, and Labour was heading to an almost certain defeat. The party’s leader, Andrew Little, knew his personal popularity was dragging their chances down. He just wasn’t connecting with voters. After a moment of reflection, he resigned as leader and asked his 37-year-old deputy, Jacinda Ardern, to take his place.

It was a rare act of political selflessness – an older, more traditionally qualified Pākehā man standing aside for a young woman. Ardern immediately became the youngest-ever leader of the Labour Party and, within months, New Zealand’s youngest prime minister since 1856.

It was a pivotal moment for Ardern’s career – and for Little’s. If he’d held on and led the party to another blowout loss, he may have gone the way of Shearer and Cunliffe; tossed to the side and remembered as a political failure.

Instead, he was embraced by the party and applauded for his decision. He flourished as a senior cabinet minister. He was able to focus on his strengths in governance, without the pressure of the popularity contest of leadership. There was a weight off his shoulders, he was more authentic and more confident. He grew out his beard, changed his personal fashion style, and embraced his elder statesman role.

In this year’s Wellington mayoral election, the roles are reversed. Tory Whanau, the 42-year-old wahine Māori from the Green Party, stepped out of the race, clearing a path to victory for Andrew Little, the 59-year-old former Labour cabinet minister.

In 2017, Andrew Little was the flailing communicator who struggled to connect with voters. His “angry Andy” schtick sounded hoarse and desperate. Jacinda Ardern, by comparison, was a world-class communicator who knew how to capture an audience.

In 2025, Tory Whanau was the one with the communication struggles. She flubbed several live interviews, sounding defensive and unsure of herself. Her political inexperience showed. Andrew Little, by comparison, had an assured confidence forged in the fires of parliament.

Jacinda Ardern and Tory Whanau are two progressive female leaders of a similar age, whose careers are both intricately linked to Andrew Little. But that’s where the comparisons end.

As prime minister, Ardern was a cautious and calculated operator. She intentionally avoided politically risky policies and didn’t take on fights she couldn’t win (capital gains tax, the cannabis referendum and the recommendations of the tax working group). She largely maintained discipline in her cabinet, especially within her own party. She was at her best when national disasters struck: compassionate but assured.

As mayor, Whanau could have benefited from a greater sense of caution – or at least some more experienced advisers. She stumbled into issues without properly appreciating the risks, most notably the Reading Cinema deal and the airport sale. At times, she alienated councillors who should have been on her side or put too much trust in rivals who ended up stabbing her in the back. When you put high-profile issues on the table but can’t get them done, it screams instability. And voters abhor instability.

The main progressive criticism of Ardern’s government is that she played it too safe. Labour had the first outright majority under MMP but had little to show for it in terms of nation-shaping reforms.

Whanau, meanwhile, will walk away from her three years as mayor with a significant progressive legacy. On housing, she passed the new high-density District Plan. On transport, she oversaw the rapid rollout of a cycle lane network. On inner-city vibrancy, she signed the construction contracts to begin the Golden Mile upgrade on Courtenay Place. The Golden Mile is an issue Whanau cares so much about that she said she was willing to lose the mayoralty over it. She pulled out of the race one day after she attended the project’s ceremonial sod-turning. Whanau can also claim to be the only mayor in decades who adequately funded the city’s water infrastructure.

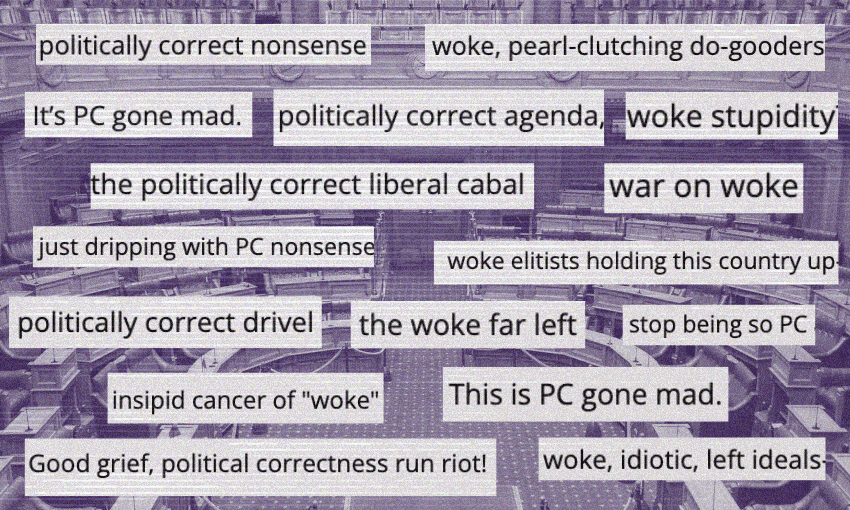

What Ardern and Whanau have in common is their ability to generate such intense anger in some voters. The bitter comments of “I can’t stand that woman”, spat with an intensity that was often disproportionate to their actual policies and actions. But that probably has more to do with society at large than either of them as individuals.

When Ardern stepped down as prime minister, she left the political arena. Tory Whanau wants to stay in it. She is running for Te-Whanganui-a-Tara, Wellington’s Māori ward, an open seat after Green councillor Nīkau Wi Neera decided not to seek re-election. Labour has put up a strong candidate in Matthew Reweti. The ward itself will face a referendum over its existence, but it’s unlikely to be at risk.

As a former mayor, Whanau would bring a level of mana to the ward that it hasn’t had before. And there’s a good chance that if Little wins, he will make her deputy mayor, either by choice or due to pressure from the Greens. Whatever the outcome, it seems Whanau’s story isn’t over just yet.