After US strikes on three nuclear facilities in Iran, social media has been flooded with memes about a world war starting. Two experts explain why we might be concerned about this – and why it might not be a useful reference today.

Being alive and online in 2025 is to live in a permanent state of whiplash. Responses to global events career along the same algorithmic highways, and bear the same weight, as ads for pubic hair razors. The signals that give information a hierarchy aren’t being received by many. Everything is noise. Anything can be parody, fact or a lie and anyone can be an authority.

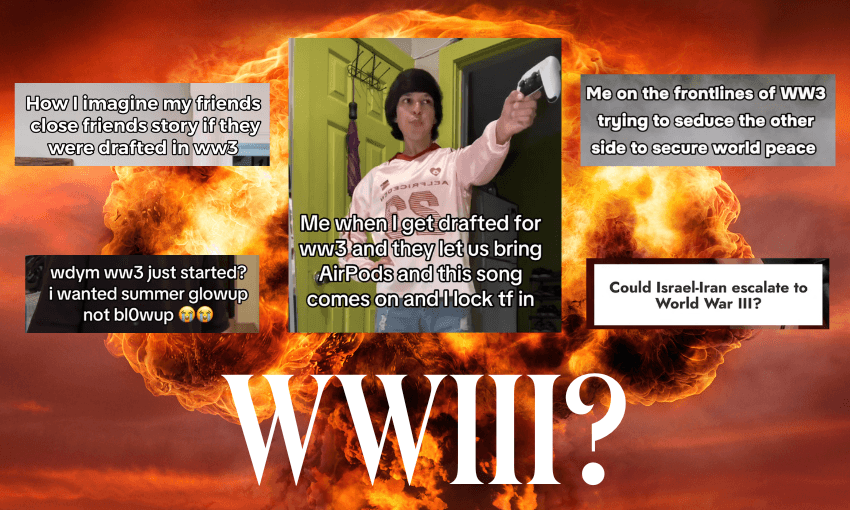

Since news broke of US military strikes on three of Iran’s nuclear facilities over the weekend, after a week of conflict between Israel and Iran prompted by Israel’s attacks on Iranian nuclear and military sites, my social media feed has been a jarring and completely normalised juxtapositional hell. A lava flow from a genre I’ll call comedic millennial nihilism pushed videos about being conscripted to fight in World War III, AirPods still in as Nicki Minaj’s ‘Starship’ dropped, alongside heated debates about whether the costuming of the actress playing Carolyn Bessette-Kennedy in Ryan Murphy’s latest series is right, surreal videos of a saxophonist playing on a Beirut rooftop as missiles flew overhead, and ads for ‘scaping your bush.

Doing it for the lols and the views aside, the addition of the Israel/Iran/US conflict to an already large slate of destruction, war, suffering and injustice around the globe seems to have tipped people, especially those who belong to the “polycrisis generation”, into a new phase of fatalism and concern. Search queries for “world war three” in New Zealand hit 100 in Google’s search trend index on June 23 (a value of 100 is peak popularity for a term). This was accompanied by searches for “has world war three started” and “is world war three happening now”. A YouGov survey in May showed that between 41% and 55% of people in Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Spain think that another world war is likely to occur within the next five to 10 years.

Talk of World War III isn’t confined to anxious citizens either. US president Donald Trump warned Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy that he was “gambling with World War III” during their heated Oval Office meeting in February. Trump’s former adviser on Russia, Fiona Hill, has warned of the prospect of World War III. When asked if she wanted the job before being confirmed, Tulsi Gabbard, Trump’s director of national intelligence, said, “If there’s a way I can help achieve the goal of preventing World War III and nuclear war? Of course.”

A world war, using conventional definitions, is an international conflict that involves most or all of the world’s major powers. Alexander Gillespie, a professor of law at the University of Waikato and author of a series of books on the causes of war, says the essence of a world war involves superpowers “really going for each other” and extends beyond regional or proxy conflicts. The terminology is also distinctly attached to two wars, the last of which ended 80 years ago. In the context of today’s world, what does “world war” mean, and how likely is a repeat of global conflict at that scale?

Both Gillespie and Robert Patman, professor of international relations at the University of Otago, agree that another world war, as we might understand it using the previous two as reference points, isn’t likely. Both cite the enormous amount of technological, political and economic change since the second world war.

Gillespie cuts to the chase, focusing on the technology of war. “If you get to a third world war where you have got the superpowers unleashing, it’s nothing like what would happen in World War II. It’s an extinction event.” To be clear, he is referencing the detonation of nuclear weapons. Gillespie notes that some people might have images of Hiroshima in their minds when they imagine nuclear war, something horrific but able to be observed from afar without widespread consequence. As he points out, the device used in Hiroshima was 15 kilotons, and it’s now common to have devices over 150 kilotons.

“The warfare in the 21st century is as different [to the two world wars] as the warfare of the 20th century was to Napoleonic times. It’s such a quantum leap, and yet, many people assume that it’s still going to be like World War II,” he says.

The prospect of a nuclear apocalypse isn’t comforting, but Gillespie’s key point is that warfare has changed so drastically since World War II, with more than 9,000 nuclear weapons now in existence, that “world war” as we might think of it isn’t really a useful framework to use in 2025 – and that the prospect of nuclear obliteration isn’t something “sane, rational” people or actors want. “There’s no winner. There’s absolutely no winner. You don’t get up to go to work the next day, it’s not something that humanity can survive, and so we’ve got to use everything in our power to make sure that it doesn’t occur,” he says. The risk, he says, is posed by the accidental, inadvertent or non-rational actor trying to trigger it.

Patman doesn’t think talk of a new cold war or World War III does justice to how different the world is now compared to the 1930s or the circumstances in which the cold war emerged from the second world war, nor does he think that a third world war is imminent. He points to the “abysmal” failure of unilateral action taken by superpowers, as well as the world’s interconnectivity and economic interdependencies, as some of the reasons why he thinks we’re not staring down the barrel of a repeat of either.

Pushing against the “drumbeat” of calls that say we’re on the verge of World War III because of the actions of one superpower in specific regions, Patman points to the track record of great powers acting unilaterally. He cites the “fiasco” that was the US in Iraq, China in the South China Sea and Vladimir Putin saying Russian military action in Ukraine would be over in a week. He points to a 21st-century paradox of power: “Great powers today, like the United States and China, are more powerful than the great powers of the past, but their scope for using that power has been reduced.” Patman’s reasoning is that many of the problems we face, such as climate change, pandemics, transnational terrorism and financial contagion, do not respect borders and cannot be fixed unilaterally.

“Putin and Trump are fragile monsters, in the sense that they can’t run the world. If they could, they would. They can’t,” Patman says. Trump’s frustration at what might be categorised as an example of the impotence of superpowers was on full display yesterday when he lost his rag about an initial faltering in the Iran and Israel ceasefire. “We basically have two countries that have been fighting so long and so hard that they don’t know what the fuck they’re doing,” he said.

Economic interdependence between superpowers creates another constraint for superpower-on-superpower warfare. “The economies of the two biggest superpowers are inextricably interlinked,” Patman notes. China’s rise came through the global market economy, with the US as its top export destination. The imposition and walkback of tariffs highlights this, says Patman. “You can impose tariffs on other countries, but they come back to bite you.”

Our interconnectedness, says Patman, also “makes decision-making, particularly for authoritarian governments, but also for democratic governments” more difficult. “Being able to create a scenario where you contemplate a global war would be a big ask. [Interconnectedness] has created what Clausewitz, the great Prussian strategist, would call friction. It’s more difficult for governments now to seal off their population from the rest of the world, and to prepare them for prolonged confrontation.”

Patman also thinks there are some inauthentic and politically motivated reasons for stirring up fear about World War III, citing Trump’s words to Zelenskyy and Gabbard’s stirring and war-mongering patriotism. “It’s a way of pressurising people to accept what they would not otherwise accept.”

If you were being unkind about the stirring up of war rhetoric and casual mentions of World War III, you might quote Harry Frankfurt, who said, “Bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about.” If nihilism is your poison, the fervent posting about it is Neil Postman’s nightmare made real, and we are “amusing ourselves to death”. Patman holds a more empathetic and measured view.

“Some people genuinely are concerned, and that genuine concern is linked to a lack of global leadership,” he says. He lays that at the feet of the “completely dysfunctional” and “marginalised” UN Security Council, which is at the mercy of the power of veto held by France, Russia, China, the United States and the United Kingdom. He cites the failure of the United States to deliver a ceasefire in Gaza, while using its power on the Security Council to veto UN calls for an unconditional ceasefire five times, as an example of why people have lost faith in global leadership and the failure of unilateral action by superpowers.

Patman does have hope, though. He thinks we’re in an “awful international transition”, “caught between a picture of alarm and hope”. For him, the hope lies in some of the reasons he doesn’t believe we’re on the brink of World War III: our interconnectedness and interdependency. He looks at the problems that don’t respect borders and thinks of them as a stimulus for ultimate cooperation. He also thinks there’s an opportunity for “the rise of the rest”, the countries that aren’t superpowers but could still take on global leadership roles if they spoke up. He does see some parallels between now and the 1930s, however, but notes that one of the main lessons from that time was that you should not reward aggression.

Gillespie has been pushing back on the World War III rhetoric “because I don’t want people to start freaking out that the end of time is just around the corner”. But he acknowledges volatility, particularly with regard to non-rational actors and a US president who doesn’t believe in the rules-based order, and risk, especially “if we don’t get our shit together”.

Both Patman and Gillespie offer some reassurance about the likelihood of a world war occurring that counters the fervour and panic of our hierarchy-free information environment, but there are uncomfortable truths in what both experts say. The world has undergone a fundamental shift, one that raises questions about whether the concept of a world war is an outdated map for navigating genuinely new terrain and whether the stakes are now too high for superpowers to engage in direct, large-scale military conflict. However, the continued escalation of proxy and regional conflicts, a lack of global leadership, nuclear armament, and the involvement of “non-rational actors” offer more than enough reason to understand why our Google search histories and social media feeds appear as they do.

We’re not idiots, we’re just anxious, exhausted and waiting for the rise of the rest. The whiplash continues.