A New Zealand Olympian is racing under Israel’s banner – and critics say it’s time to choose sides.

10.41am update: An earlier version of this story suggested Corbin Strong was a shoo-in for selection for the Tour de France team. He has not been selected but remains in the Israel–Premier Tech squad.

A Palestinian paracyclist who lost his leg in an Israeli air strike over a decade ago was killed in Gaza last month. Ahmed al-Dali, 33, a father of four, spent his life defying disability on a bicycle. Initially declared dead in a 2014 strike, he was later found alive in a morgue. Since October 7 2023 his team, the Palestinian Sunbirds, have distributed NZ$760,000 in aid across Gaza amid ongoing Israeli attacks.

While conflict continues to expand in the region, on the other side of the West Bank, Israel’s most elite cycling team, Israel–Premier Tech, is currently training for the Tour de France.

The team, which takes part in the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia – the biggest male cycling races in the world – receives partial funding from the Israeli government.

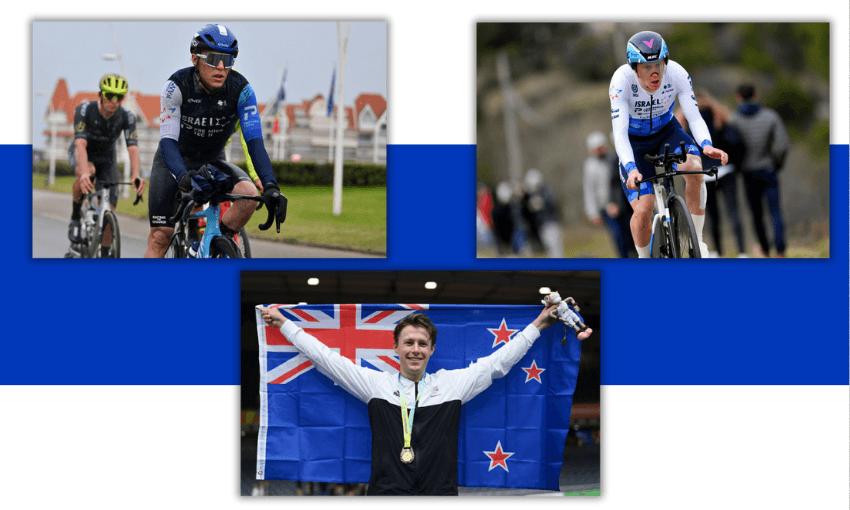

Two of those riders, including one of Israel–Premier Tech’s stars, Corbin Strong, are New Zealanders. Strong represented New Zealand at the 2020 and 2024 Olympics, and earned a gold medal at the 2022 Commonwealth Games.

Despite repeated requests, both the New Zealand Olympic Committee (NZOC) and Cycling New Zealand (NZC) declined to comment on Strong’s dual affiliation with Team New Zealand and the, in part, Israeli government-funded Israel–Premier Tech.

Israel–Premier Tech is founded and owned by Israeli billionaire Sylvan Adams. Adams refers to himself as “the self appointed ambassador at large for the State of Israel”. Friendly with both Benjamin Netanyahu and Donald Trump, Adams frequently promotes Israeli propaganda, referring to the conflict between Israel and Palestine as “good vs. evil” and “civilisation against barbarism”.

At this year’s Giro Italia, protests from sports and cycling associations, Palestine solidarity groups, and human rights groups including Amnesty International disturbed the race at numerous points. The disruptions were so frequent that the live television coverage was forced to repeatedly acknowledge the protests and the calls to ban Israel–Premier Tech.

At each race, “ISRAEL” is emblazoned across every Israel–Premier Tech rider’s chest, a moving billboard for a government accused by the UN of war crimes and potential genocide. A former team member, Guy Niv, has said riders understand that “being on an Israeli team, they are ambassadors for the country”.

No ban has been handed down by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI), prompting allegations of double standards.

“UCI excluded Russian and Belarussian cycling teams and prohibited UCI sporting events in the two countries, among many other sanctions,” says Stephanie Adam of the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, a founding member of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

“It did so because it fully understood that cycling could be used to sportswash Russia’s illegal occupation. Yet UCI, demonstrating staggering levels of hypocrisy, has failed to take any action against Israel’s cycling team as Israel’s genocide against 2.3 million Palestinians in Gaza has raged on.”

The UCI has said it remains focused on sport and not politics, according to comments made to Cycling Weekly. Historically, the UCI has followed the guidelines of the IOC.

Despite repeated ceasefire attempts, attacks on Gaza have entered their 20th month, with over 53,000 Palestinians confirmed dead, according to Al Jazeera. The New Zealand government has repeatedly condemned several actions of the Israeli government and recently joined 23 other countries and the United Nations in calling for humanitarian aid to resume.

The 2025 Tour de France is just days away. Invercargill-born Strong has not been selected to ride for Israel–Premier Tech, despite earning a podium place at the Giro d’Italia in May.

What is certain is the prospect of protests. In April, the BDS movement called for peaceful actions at this year’s Grand Tours, to demonstrate against Israel–Premier Tech’s participation.

Is Israel–Premier Tech sportswashing for Israel?

Sportswashing is a relatively new term, first used in 2015 by human rights advocates to describe how Azerbaijan used major sporting events, including Formula One, to deflect from human rights violations. But according to Steve Jackson, an academic at the University of Otago, the practice can be dated back to ancient Rome and is depicted in films like Gladiator.

Sportswashing happens when “political entities use sport as a vehicle to deflect political issues via entertainment,” says Jackson. “It is the deliberate and strategic use of sport, events, athletes, teams to enhance the reputation of a nation-state or a corporation. And conversely, to hide or camouflage their ethical violations, including those associated with human rights.”

Cycling, a sport without a strong tradition of political activism, has often attracted sponsors with deep pockets – and not always spotless morals – due to the high cost of running elite teams. The British team Ineos Grenadiers, for example, is sponsored by Ineos, one of the world’s largest petrochemical companies. New Zealand Rugby also signed with Ineos in 2021, prompting sharp criticism, including by Greenpeace who said it went against our country’s clean, green values.

Sylvan Adams has explicitly described the Israel–Premier Tech team as apolitical, despite being deeply political himself. The Times of Israel describes it as “a private initiative meant to boost Israel’s image worldwide”.

Sport and politics have always mixed for Adams. He led Israel’s $18m bid to host the start of the Giro d’Italia in 2018, the first in a series of international sporting investments. Additionally, he “has worked to change Israel’s image among non-Jews through high-profile sports and cultural activities,” according to an interview with Jewish News Syndicate.

Today, Israel–Premier Tech’s presence in the Tour de France presents Israel as open, peaceful and globally connected, defined by elite sport and international recognition. This image contrasts sharply with the actions of Israeli politicians and the IDF, who “have incited extremist violence and serious abuses of Palestinian human rights”, according to foreign minister Winston Peters.

The Springbok Tour, politics and sport in NZ

New Zealand has its own turbulent history with sport and politics.

The 1981 Springbok Tour sparked widespread civil unrest in Aotearoa. For 56 days, 150,000 people protested South Africa’s apartheid regime.

The NZ Rugby Football Union “should have joined the sports boycott of apartheid South Africa,” says former All Black Robert Burgess, who turned down an invitation to trial for the All Blacks’ 1970 South Africa tour.

Burgess refused the trial “as a protest against apartheid and the way sport in South Africa was segregated on race”. Five years earlier, he also turned down the 1976 tour of South Africa, where five Māori players were granted “white status” for the trip.

That same tour prompted 25 African nations to boycott the Montreal Olympics in protest against New Zealand. Today, there is widespread agreement that Burgess was on the right side of history – and the NZRFU was not. In 1964, the IOC banned South Africa from the Olympics due to its refusal to denounce the ongoing apartheid; this ban was only lifted in 1992.

Many would consider what Burgess did to be above and beyond the call of duty as an international rugby player. So, what can we expect of today’s elite athletes?

Israel–Premier Tech and two-time NZ Olympian Corbin Strong receives part of his pay cheque from the Israeli government and frequently wears Israeli-branded clothing. He and teammate George Bennett represent both New Zealand and Israel. While representing Team New Zealand at the 2024 Paris Olympics, Strong announced a two-year contract extension with Israel–Premier Tech.

Strong is not the only non-Israeli rider on the team. Australian Simon Clarke was protested against during the Australian National Championships in 2024 for representing an Israeli team. In response, Israel–Premier Tech released a statement, saying, “We are the only professional sports team in the world that includes Israel as part of its name, and we will continue to do so and proudly represent the country”.

NZOC and NZC were contacted for comment on Strong’s joint relationship with both NZC and Israel. Both declined interviews. It remains unclear whether Strong will continue to be allowed to ride for both New Zealand and Israel–Premier Tech. Strong did not respond to a request for comment for this story.