Bridget Mahy reflects on what it was like to grow up with the beloved writer and witness the construction of her stories.

‘Imagination is the creative use of reality’

My mother once described herself as a “slave to fiction”. From a very young age, her parents would find her “conducting unseen orchestras of stories, stories remembered, recreated and invented”. She would incessantly verbalise her ideas until she was old enough to write them down. And because of this powerful, intrinsic drive to respond to the world through narrative, she never stopped conducting.

Margaret looked to build bridges between the constructive truths of fact and reality, and the transformative truths found in the imaginative world. She wanted to peer through the looking glass, to take the riddles of a paradoxical reality and give them meaning in an alternative world. This led her down paths of wordplay and absurdity: a tone akin to Lewis Carroll but infused with her own particular humour. In part, her job was to entertain herself as much as her readers – both child and adult.

A powerful influence on Margaret were the European folk and fairy tales she devoured as a child. They continued to shape her imagination, offering conduits between the real and the imagined. Margaret felt they gave her a kind of “code by which to decipher experience”. Drawn to the ebb and flow of high drama, their struggles of good vs evil, magical reality and gothic romanticism, she fell in love with the spectacular imagery, archetypal figures and the rhythmic patterns of their structure. The language of mystery and the magic of fairy tales are interwoven into her stories.

One example is a picture book called The Railway Engine and the Hairy Brigands. The hardback edition, illustrated by the fabulous Brian Froud, was published in 1973, and I was fascinated to turn its pages for the first time and discover that the heroines of the story were “Penny and little Bridget”. My mother had placed my older sister and myself at the heart of a tale in which we ran the cheerful (but annoying) hairy brigands out of town. With no effort at all on our part, we had been cast as heroes.

I can readily imagine Margaret deliberately inserting her daughters into the story as a gift to us. We officially existed within both her storytelling codes and her day-to-day world. It was a potent reminder that our mother had one foot firmly placed in the life of a working solo parent, yet could escape that tough reality through creative endeavour.

The House is a character

Over time, Margaret built a house around herself. Here was a structure that was both tangible and strong, offering shelter to a small family and a menagerie of pets. Our house became something of a sanctuary, a sometimes-successful hiding place where solitude and silence could flourish in the face of too much intrusion.

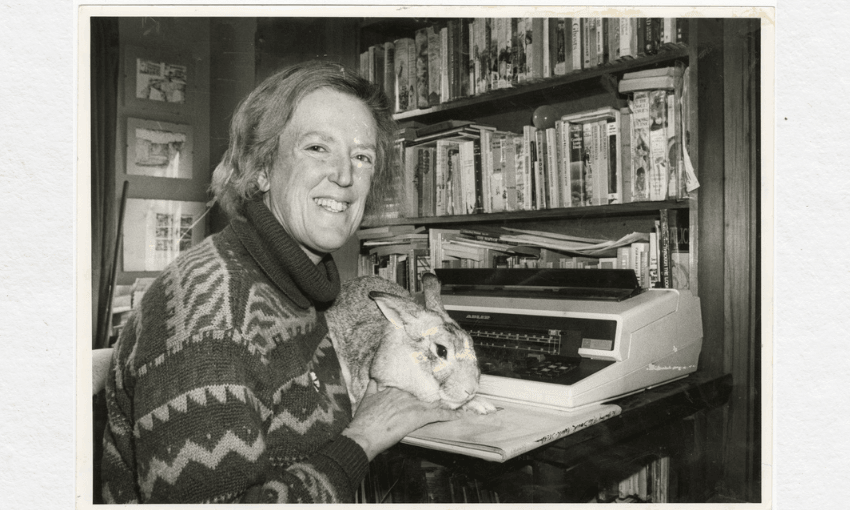

Bookshelves crept up and out like vines from ceiling to floor. The librarian wanted to live in a library, and the writer enjoyed the semi-organised jostling of other people’s ideas. The house itself took on a role in her stories. For 40 years, the writer and the house went hand in hand, utterly inseparable.

I can only imagine Margaret’s relief at the end of the working day as a librarian, after putting her young children to bed, to claim some hours for herself. Reading or writing into the early hours in her small bedroom must have been its own form of escapism, freedom from the repetitive slog of processing daily life.

While Margaret could do a lot, she couldn’t do it all. So she hired a neighbour to clean the house twice a week, in an effort to stem the inevitable entropy of a home with one adult juggling two jobs, two children, any number of muddy pet paws – the chickens were particularly painful when they elected to try and move in.

However, Margaret would bemusedly tell friends how, too embarrassed to let anyone see a trail of domestic detritus, she would cajole the children into helping tidy the house for the cleaner.

This episode formed the basis of a picture book called The Housekeeper. “The house Lizzie Firkin, the songwriter, lived in was particularly untidy. It was a rough and tumble house, unwashed, undusted and topsy turvy. When she opened the cupboard doors, a thousand things with sharp corners fell out on top of her. So she nailed the cupboards shut.”

I’m rather fond of this story, not only because Margaret uses reality to her creative advantage, but also because she and Lizzie share a moment of comic solidarity over their need for help. While Lizzie’s rescuer, Robin Puckertucker the “Wonder Housekeeper”, is deeply disappointed, I suspect Margaret’s cleaner was quietly relieved.

Part of the the flotsam and jetsam that covered Margaret’s large study desk, and spilled into its drawers, were small notebooks: a couple of very elderly ones still hanging on; one chewed by the dog; one falling apart; one given to her at a conference; one with a leftover primary school spelling list; and one marked with the ubiquitous coffee stain.

None were to be thrown away. Yet when I randomly opened them, they all showed the same thing: the raw mechanics of piecing together poetry.

Inside were small lists of rhyming words, the 26 letters of the alphabet, quotes, snatches of half-finished sentences, varying rhyme schemes, wordplay experiments and collections of words chosen for their sound. A poem of hers comes to mind:

Through my house in sunny weather

Flies the Dictionary Bird,

Clear to see on every feather

Is some outlandish word.

‘Hugger Mugger,’ ‘gimcrack,’ ‘guava,’

‘Waggish,’ ‘mizzle,’ ‘swashing rain’ —

Bird, fly back into my kitchen,

Let me read those words again.

When Margaret had a light-hearted poem well underway, the performer and conductor within would emerge. It was charming to hear her confidently reciting sections, editing as she went, entertaining herself with the search for successful rhythm and rhyme. She would sound out extended poems to family members as though she couldn’t believe her good fortune that the selected words were not only alliterative, but were also dutifully conforming to her version of anapestic tetrameter.

“Little Mabel blew a bubble and it caused a lot of trouble…

Such a lot of bubble trouble in a bibble-bobble way.

For it broke away from Mabel as it bobbed across the table,

Where it bobbled over Baby, and it wafted him away.”

Nineteen stanzas later, the baby in the bubble is safely returned home. Margaret would go on to regularly, cheerfully, heroically recite this epic poem to thousands of children.

A quieter version of my mother was revealed in the way she murmured to herself while fine-tuning ideas for a novel. As chief instigator, director and actor, Margaret could often be found role-playing an ensemble of quite distinct characters: mothers, fathers, precocious children, 14 year olds, an elderly woman with Alzheimer’s and menacing tricksters. Her boundless curiosity fed a complex interior world, and on occasion, that world had to be made real, by chasing her ideas into the open and speaking them out loud.

Away from the keyboard and the drafted word, she murmured as she stirred a wholesome soup, inspected the burnt edges of a grilled cheese toastie, or walked the dog down the long jetty. I could hear her softly, experimentally expressing her characters’ shifting tones of voice, trying to capture the tempo of nuanced dialogue and giving voice to their private thoughts.

The bridge builder

I sometimes hesitate to open the pages of my mother’s teenage novels. And yet, when I return to The Haunting, The Changeover, Catalogue of the Universe, or The Tricksters, the words resound with her voice, incredibly immediate and incredibly distinct. Time collapses.

These novels explore the intricacies of family life. Her characters are tightly bound by strong familial relationships that shift and evolve as the adolescents are transformed by mysterious or supernatural experiences, and ultimately see themselves in a new light.

My great privilege was to hear these stories take shape with manuscripts repeatedly refined and road-tested on a willing volunteer as they inched forward in creation. Like any writer, Margaret wrestled with her novels, looking for a delicate balance in an unwieldy creation. Not so much control, as dabbing detail into all the available spaces. When she read aloud from her handwritten volumes or typewritten pages, I sat beside her knitting a scarf that, like the story, didn’t know how it would end. She stopped and started, paused, scribbled, swapped words until (unlike the scarf), we reached a finale.

Once all the words were finally gathered and polished, I could see the facets of her ordinary life made extraordinary through the writing: Christchurch itself, Canterbury’s weather patterns, domestic responsibilities, elderly car issues, house maintenance, a missing septic tank, the alternative life a writer, family dynamics, Christmas, cats, art, culture, science, memory, astronomy … the list goes on.

Although Margaret’s characters are inventions, they also reflect her own interests, childhood memories, daily experiences, archetypes and the personalities of her wider family. Unsurprisingly, there are unmistakable intonations of Margaret herself. On occasion she is her own archetypal figure – surprise! The writer!

When Margaret was finally able to take a risk and become a full time writer, her first significant teenage novel was The Haunting (1982). Margaret introduces two sisters – the mysterious Troy, described as “stormy in her black cloud of hair”, and the effervescent, talkative Tabitha. Tabitha says that she is writing “the world’s greatest novel but that no one could read it yet. However, she talked about it all the time.” By the end of the story, Troy, once silent and watchful, has become the indomitable talker, and by contrast, Tabitha feels defeated by being overtaken by her sister. “Everyone else can be a magician or haunted, and that leaves me stuck with ordinariness, though I was the one who didn’t want that in the first place…”

Margaret later reflected that she saw in these characters a duality of her own life and an early love of romanticism. As a child, she had longed to be dark and mysterious, made powerful and magical through silence, but was confronted with more prosaic truths. Margaret says: “Tabitha was quite the self-portrait: the talkative girl who wants to write, managing to mention my stories into conversations in an effort to show other people how interesting I was.” By the end of the writing process, she adds, “I had written all about myself without ever once realising. Now that’s scary.”

A short story Margaret wrote for older children was called ‘The Bridge Builder’. Margaret’s father, a construction builder, worked on bridges in the Bay of Plenty during the 1940s and 1950s. “Like a sort of hero, my father would drive piles and piers through sand and mud to the rocky bones of the world,” she recalls. In the story, the bridge builder raises a family and constructs purely functional bridges, bridges to be driven over. But later, after his three children have grown and his wife has died, he is released from his domestic responsibilities and finally builds the bridges he had only seen in his dreams.

He builds a bridge out of black iron lace and releases a hundred orb-web spiders onto the iron curlicues to spin their own lace, and after a night of rain “the whole bridge glittered black and silver, spirals within spirals”. Another creation is the “mother of pearl bridge only to be crossed in moonlight at midnight”. Now the people crossing over these surprising bridges “became part of a work of art”.

Margaret was proud of her father and the ability to point out his bridges as they drove along. I rather like to think of Margaret and her father both conducting productions, one shaping the tangible, the other crafting eloquent ideas; each building bridges, linked by the art of transformation.

The author would like to thank the following books for their help: Margaret Mahy: A Writer’s Life by Tessa Duder; Dissolving Ghosts by Margaret Mahy; The Word Witch: The Magical Verse of Margaret Mahy by Tessa Duder.