The best tour of Wellington costs just $4.34 with a Snapper card.

On most bus trips, efficiency is paramount. The goal is to get from A to B, cheaply and (ideally) quickly. But there are those occasional, special moments, where you can just settle in and enjoy the journey. Stare out the window, put your headphones on and pretend you’re the main character in a music video.

For commuters in Johnsonville and Miramar, the Number 1 and Number 2 buses, respectively, are the fastest and most direct routes, charging along motorways and through tunnels. Then there’s the Number 24. In the family of east-north bus services, it’s the distractible younger child who runs off chasing butterflies and talking to their imaginary friends.

The number 24 was created in Metlink’s 2018 redesign of the bus network, a mashup of parts of the old 46, 50, and the old 24. It meanders through forgotten streets, winding its way up hills and around coastlines. It’s not a high-frequency route or a particularly well-patronised one. Really, it’s a minimum viable product designed to service some of Wellington’s lower-density neighbourhoods. But what Metlink cobbled together is nothing short of remarkable.

One Sunny afternoon, I rode the entire length of the Number 24 route. I’m now fully convinced that it is the most beautiful bus ride in Wellington – and the perfect way to see the best of the city on a budget. Let me take you on a tour….

Our journey begins at Miramar Shops – Stop A. Miramar, which is Spanish for “sea view”, is a lovely shopping village with excellent op shops and cafes. Stroll around Palmers Garden Centre as you wait, or check out the film memorabilia at The Roxy Cinema. Miramar is a thematically appropriate place to begin a tour of the city because it is the first place on the Wellington mainland to be populated by humans. The first inhabitants, Ngāi Tara, called this area Te Motu Kairangi, meaning the island of high quality or esteem.

The bus sets off, turning around Polo Ground Park, then begins a winding uphill stretch up Awa Road. Near the top of the hill, we turn past Worser Bay School. This is the former site of Te Whetu Kairangi, the first and most important pā established by Tara, the founding chief of Ngāi Tara and the namesake of Te Whanganui a Tara.

Along the ridgeline, there are views to our left of Wētā Workshop and Wētā Studios’ large campus, and to our right, the glistening blue of Karaka Bay and of Mākaro, one of two islands inside Wellington harbour, which the early explorer Kupe named after his daughters.

At the end of the peninsula, the road narrows to a single lane. The surroundings become semi-rural, with farm bikes, wooden fence posts, and unkempt gorse bushes. Then, a rare sight: an up-close view of the abandoned Mt Crawford Prison, first opened in the 1920s and closed since 2012. It still has barbed wire around the exterior and, on the day of my ride, a police officer watching the front gate.

The road turns inland, and we’re treated to more stellar views. From the top of the Mt Crawford, Evans Bay looks as serene as an alpine lake on a winter morning.

We wriggle downhill through some quiet scenes of late-20th-century suburbia, until we are almost back where we started. The bus turns right through the Miramar cutting, then heads towards the low-lying Rongotai isthmus. Māori legend says Rongotai is the dried-up body of the taniwha Whātaitai, who tried to break free of the harbour with his brother Ngake, but got stuck between the sea floor and the hills. Geological research and Māori oral history tell us that Rongotai was raised from the sea by the Haowhenua earthquake in approximately 1460.

After a rather uninspiring detour through Kilbirnie (Feast your eyes on the Pak’nSave! Gaze in wonder at the KFC drive-thru!), the bus turns back out to the Evans Bay coastline past a local landmark, the Zephyrometer, a 26-metre tall needle which waves to show wind direction and speed.

The coast road passes by the Evans Bay Yacht Club, sailboats bobbing in the water, the iconic Havana Coffee boatshed, and quiet pebble beaches. This is a great section for people watching – Evans Bay Parade is a popular spot for running, biking, fishing and plane spotting.

Heading towards Point Jerningham, there’s a great view of Matiu, the second, and much larger, harbour island. Matiu is now a nature sanctuary run by DOC and Taranaki Whānui, with regular access via the East by West ferry.

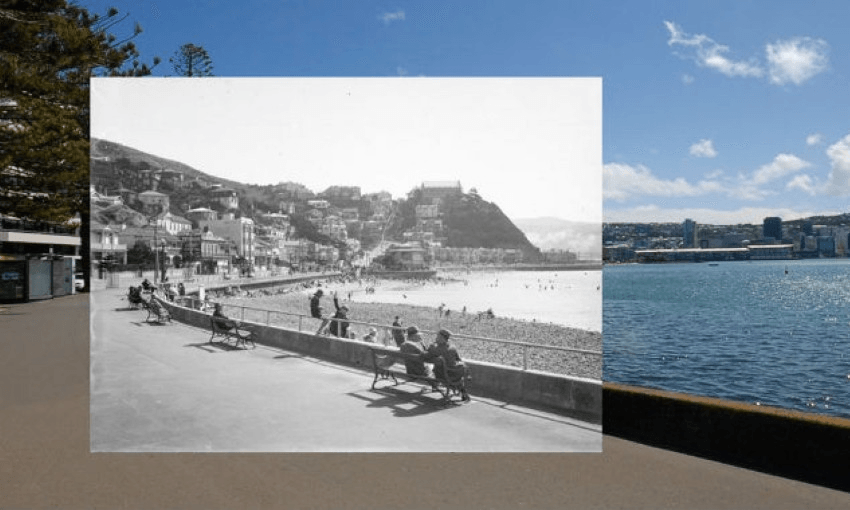

As the bus turns towards Oriental Bay, we’re treated to my favourite view of Wellington: glass towers of the city across the bay, under a bright blue sky.

Oriental Bay is a stunning bit of waterfront, and the Number 24 is one of the few buses that traverse it; most take a more direct route through the Hataitai bus tunnel. The waterfront is lined by mature Norfolk pines. The Carter Fountain sprays 16 metres into the air. In summer, crowds cram in to enjoy the golden sand at Oriental Beach.

As the Number 24 reaches the city, it joins almost every other bus route by heading along the main public transport spine, the Golden Mile. Along Courtenay Place, past Te Aro Park, Cuba Street, and through Lambton Quay, past the Beehive and Old Government Buildings. The seats rapidly fill up with city workers on their way home.

After a quick break at the train station, the bus is off again. There’s a frankly quite boring stretch along Thorndon Quay and Hutt Road (unless you’re the kind of infrastructure nerd that loves looking at rail yards and the underside of motorway viaducts), but then things get interesting again. We turn up Onslow Road towards Cashmere, climbing up steep, winding roads that seem far too narrow for any bus.

That’s where another gem of the Number 24 experience reveals itself: the view of the harbour and city from the side of Mt Kaukau. It’s the same harbour we’ve been watching the entire journey, but from the added height, it is so much more expansive and awe-inspiring. The city beckons in the distance. At some points, there is a clear line of sight all the way to the Hutt.

The ride continues through the streets of Khandallah, a cute shopping village, gorgeous upmarket houses, and lush green trees. Everything you’d expect from the leafy suburbs. Then, a giant loop through Broadmeadows, where we reach the highest elevation of our journey, looking straight down on the dotted white houses of the city below.

The home stretch of the Number 24 bus ride follows Burma Road. We’re further inland now. No more harbour views, but Paparangi ridge makes for a nice accent against the late afternoon sky.

As we approach the last stop, I feel a pang of regret that the journey will soon be over. But like a pot of gold at the end of a rainbow, there is one final, glorious sight to behold. It stretches out from the grey, welcoming all into its arms. Wellington’s greatest tourist attraction: The Johnsonville Mall.

Final verdict

The number 24 bus is an excellent way to spend a meditative day of sightseeing. You can take the route from either end, but I would recommend starting in Miramar to get the best views around Oriental Bay. Metlink runs both single- and double-decker buses on this route. I was riding a single-decker, but the premium experience would be to ride in the front seat on the top floor of a double-decker. The Number 1 bus is the fastest way to get back to the city from Johnsonville, but I recommend taking the Johnsonville line train for a more scenic experience.

Cost: $4.34 with a Snapper card, or $8 with cash (adult fares, off peak).

Time: 1 hour, 12 minutes.