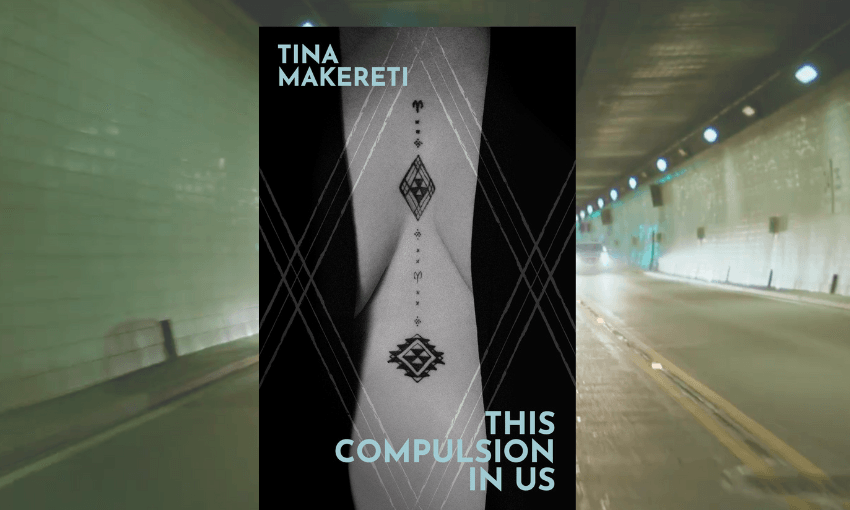

In this excerpt from her new book This Compulsion In Us, Tina Makereti writes about the night she refused to go in her dad’s car.

It is the summer of my 15th birthday when Dad has the party. It’s still the start of summer, the end of the school year, and even though it’s mostly old people at this party, I’m glad to have free access to the booze. Usually I have a friend with me, but this night I don’t, which is a relief really, considering what comes next. I don’t know if I have any friends left at this point anyway, given the way the year has gone. There have been a number of poorly judged friendships and relationships from which I emerged as lonely and lost as ever. Too many cigarettes smoked and too many awkward experiments with bogan teenage rebellion. As usual, I don’t think I’ve fooled anyone into thinking I have anything together or am cool in any way, which, embarrassingly, is probably all I want in life. I haven’t learnt to embrace my inner weirdo yet. Or her outward manifestations.

I’m in the kitchen leaning against the long Formica bench where all the drinks are lined up. Dad used to take me to the pub and give me “ladies’ drinks” like Pimm’s and shandy, but I don’t think he bothers policing what I’m drinking anymore. I’m in a conversation with Dad’s best mate, who is ten or so years younger than him and not as gross as all the other middle-agers in the room. He always has an attractive girlfriend too. This memory is 30-something years old, so I don’t know how we get to this exact moment. It’s just suspended there, this one conversation and what comes after. We’re talking about the nature of women’s orgasms, and he has it wrong.

“That’s not how it works,” I hear myself saying. I’m searching his face for some sign that he’s taking the piss, that he has some ulterior motive. I might not be any good at dealing with kids my own age, but I have impeccable instincts when it comes to adults.

“But I thought when the guy shoots his load, you know, the woman is done too.” He seems genuinely puzzled, if slightly amused.

“Nah—it’s different for her.” I’ve never actually had an orgasm, but I’ve read the collected works of Jean M. Auel and Alice Walker. Those books are educational.

“Really? I always thought that when it happens for him, it happens at the same time for her.” He pauses. It’s impossible to have this conversation without imagining him banging away at his current girlfriend, and her efforts to look completely satisfied when he finishes. How could it be that none of them have told him?

“How does it happen for the woman then?” he asks.

This is the big question. I’m not sure how to explain. It’s one thing to point out how it doesn’t happen, quite another to get into the intricacies of how it does. Anatomical words will need to be used. If I’m wrong, and if there is some other motive at play in this conversation, it could all get very uncomfortable very quickly. I’m not entirely sure why it has been comfortable to this point. People seem to be treating me like an adult. I’ve been told I look like one.

But suddenly I don’t have to explain. Suddenly Dad is there, yelling.

“What are you talking to my daughter about? I invite you into my home and you talk to my daughter like this?”

“It’s OK. She’s not worried about it.’”

“I’m worried about it.”

“It’s not a big deal.”

At this point, Dad becomes enraged. Of course it’s a big deal.

I don’t understand the fuss. Nobody else understands the fuss. I’ve spent much of the last year being dragged to pubs and house parties by my father (better than leaving me home alone), surrounded by middle-aged men and their women. I’ve seen more than a few drunken liaisons that I wish I hadn’t been privy to. But this is my dad. Some line, known only to him, has been crossed.

“Mate, I didn’t mean anything by it.”

“How dare you talk to my daughter like that! How dare you!”

People try to get Dad to calm down. But this makes things worse. Everybody get out. A punch or two is thrown and dodged. There is pushing. People are shaking their heads.

“Mate, you’re crazy.”

“Out,” he yells. “Get out, the lot of you!”

People head towards the door. Some of them are still trying to calm him down. Maybe someone asks if I’m OK. I give them a noncommittal affirmative; what are they going to do if I’m not?

Dad goes to see the stragglers off. The party’s over. Friendship too.

I retreat to the lounge. On Saturday mornings I come into this lounge and watch reruns of The Addams Family and the original Star Trek. There’s a massive 1970s rock-wall fireplace in here, two old lounge chairs beside it. Other than this, the house is mainly empty of furniture. I sleep on a mattress on the floor. It’s our third or fourth place this year, since my big sister left home. Soon it will be my birthday, the day before New Year’s Eve 1988, and the following night, while getting a ride to a party, Dad will be so drunk he’ll try to exit the car while it’s speeding along the motorway.

When we get to the party and discover how dire it is, we will both want to go home and he will insist on taking someone’s car to get there. Afraid his drunk driving will kill me, I will refuse to get into the car with him, the first time I’ve ever done such a thing. It’s not the first or the last time I will fear his drunkenness or his driving, but after a screaming row that raises the neighbourhood, we’ll walk the two or more hours home just before the first dawn of 1989, exhausted but alive.

In a couple of months we’ll leave this house. Dad will leave town and I will stay to finish high school, boarding privately. That bleak New Year’s will also be the night that saves me, since it will be the moment we both realise that it can’t go on, and Dad will eventually give me the gift of his departure and my independence.

But right now I am by the fireplace and the world is spinning. I close my eyes to enjoy the sensation. Things have gone quiet. Dad comes and sits across from me, by the fireplace.

“You OK?” he asks.

“Everything’s spinning,” I say.

“Yeah, that happens sometimes,” he says. I can tell from his voice that I’m not in trouble. The fight has gone out of him, and now he sounds gentle. He leans back, mirroring my pose.

“You gonna puke?”

‘No—I don’t think so.’

And we sit in companionable silence for a long time, the world spinning in bliss or madness, I don’t know what.

This Compulsion In Us by Tina Makereti ($40, Te Herenga Waka University Press) can be purchased from Unity Books.