Fighting on the streets of Beirut, recipes written on scraps of paper and a daring escape from near-certain death: the story of how Phoenician Falafel got its menu.

Table Service is a column about food and hospitality in Wellington, by Nick Iles.

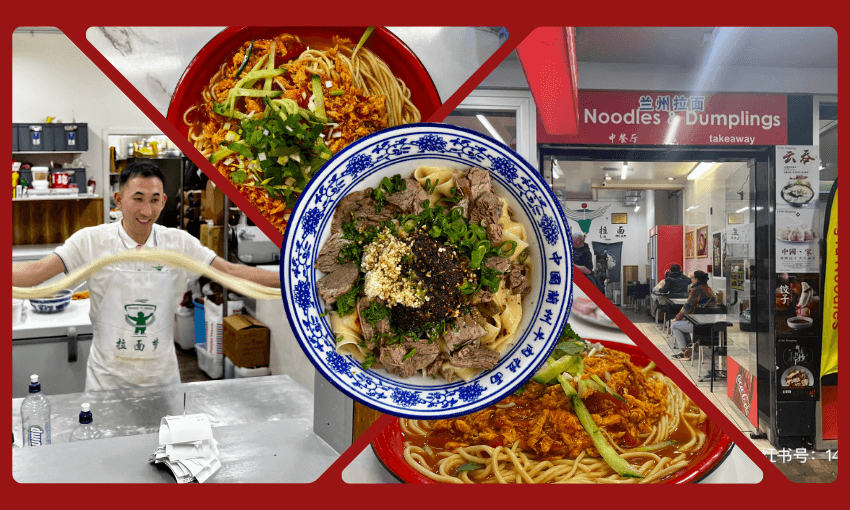

Wellington, 2025. A menu, handwritten high up on the wall above the kitchen. Yellow, red and green on a black background. Traditional Lebanese dishes. Baba ghannouj, shawarma, makanek, kibbi. Behind the counter, Yolanda Assaf cooks orders with homemade ingredients as the noise of the busy junction outside fills the space.

Beirut, the summer of 1958. While resting on the colourfully tiled floor of his living room, a seven-year-old Antoine ‘Tony’ Assaf looked up to see a bullet tear through the whitewashed walls of his home. His family gathered low in the middle of the room, all desperately praying that they would survive. The army outside was relentless in their attack; one shot came so close to a neighbour’s head that it left a permanent scar. It was the first time young Tony had ever heard gunfire.

Tony spent most of his childhood on the streets of Beirut exploring and adventuring among the fallen columns and ruins of civilisations past. Most days, he would arrive home from school only to throw his bag through the front door and leave immediately in search of more excitement. An entrepreneur at a young age, he used money he had cobbled together to buy up boxes of bright, individually wrapped bubble gum on the cheap before selling the contents on to the boys of the neighbourhood at five times the cost – until his mother caught him at it. The business was liquidated at once, and he was left looking for other forms of entertainment. Due to his keen sense of justice, this often meant fighting, looking out for the weaker ones being picked on and getting stuck in on their behalf. Before long, his reputation grew, and the other boys in his neighbourhood were told to stop playing with him. He was officially trouble.

Behind the counter, Yola cooks the falafel in a traditional circular pan. Lined up neatly around the perimeter, they’re fried so the edges turn lacy and crisp, delicate shards pointing in all directions. She assembles a heated wrap with pickles, tomato and homemade hummus. It is set to one side as she finishes the order.

It was on New Year’s Eve of 1961 that life got more serious. When walking across town to visit his uncle, Tony accidentally found himself in the middle of an attempted coup. The Syrian Social Nationalist Party had cut the military’s communication lines and besieged the ministry of defence in an attempted hostile takeover. It lasted barely four hours and is a footnote in Lebanon’s complex history, but it left a deep mark on Tony. He became politically motivated and devoured the newspapers every day. He wanted to make sure people were safe. It was with this full heart and strong head that he enlisted at the age of 20, but it was a short-lived military career. Within three months he realised the subservient life was not one for him; a superior officer tried to push him around and he responded in the only way he knew how. Tony was swiftly sent to military prison for a short sentence.

Yola shapes the beef of the makanek, a kind of Levantine sausage, by hand and throws it leftwards on the flattop to cook. She heats a wrap and generously spreads the hummus, adds a fistful of homemade gherkins and fresh tomato. Three fat makanek are lined up on top, and the whole thing is wrapped.

In 1975, Tony became engaged to Yola; they had known each other since they were children, and in 1977 were married. They were very much in love, but those early years were set against the gunfire and bloodshed of the Lebanese Civil War. Over the next 15 years, they raised four children while their neighbourhood was a near-constant battlefield. Tony did what most men in his area did: he joined the resistance and fought to keep his family and community safe.

Late in the conflict, rival forces put a bounty on his head, making a public order for his capture. It was a death sentence. He was forced into hiding and plotted a plan to escape. Food would be his means of survival.

He moved through the city quietly, calling in favours from those he trusted. In secret, he made his way to the best falafel seller in town and asked for his recipe, then to the best shawarma place, and then to the man who shaped and spiced the best makanek. They knew him. They loved him. They helped. Within weeks, he had a pocketful of recipes, all scribbled by hand and all of the best Beirut had to offer.

In 1995, Tony, Yolanda and the whole family boarded a flight to Aotearoa and settled in Pōneke. Tony carried two precious items: that stack of handwritten recipes and a $100 BBC English language cassette tape programme. This was his lifeline to the new country he was about to encounter. He hid himself away in his apartment and studied. Eight tapes and several months later, he stepped out into Wellington with his newly acquired tongue. Before long, he had secured the deeds to the bricks and mortar he would call home for the next 28 years, 11 Kent Terrace. He wrote the menu high up on the wall that first week. It remains unchanged to this day.

It is in this space and up those stairs that Tony and Yola still make every last element from scratch from the recipes written down in their previous lives in Beirut: the hummus, the baba ghannouj, all the pickles and garlic thoum. They even grind their own tahini from seed.

Yola calls my name, and I am summoned to collect my falafel and makanek, both wrapped tightly in silver foil and presented on small blue plastic trays. They focus on quality ingredients, only using corn-fed chicken and lamb fillet for their shawarma and premium topside beef for their makanek. Spices of the Levant course through the beef, vast plains of aromatics and nuance: nutmeg, cumin, paprika. The falafel is at once delicate yet firm, light but with meaning. It is laced with those familiar spices that all take their turns appearing before making way for others: cardamom, cinnamon and more. Both in a flatbread with decadent hummus, thoum, tomato and crisp lettuce for texture.

That menu, with so much more to explore, is a direct portal to Beirut in the early 1990s. It is one that has come so far and will continue its journey with their son Elie Assaf at his Auckland shop, Lebanese Grocer. It is a menu that tells just one of the many stories of Yola, Tony and their whole family. A piece of history written down by hand, wrapped tightly in foil and before us all now in this faraway country.