Part of the appeal of MMP was that it might constrain some of the worst excesses of the political executive. Right now, that is starting to look a little naive.

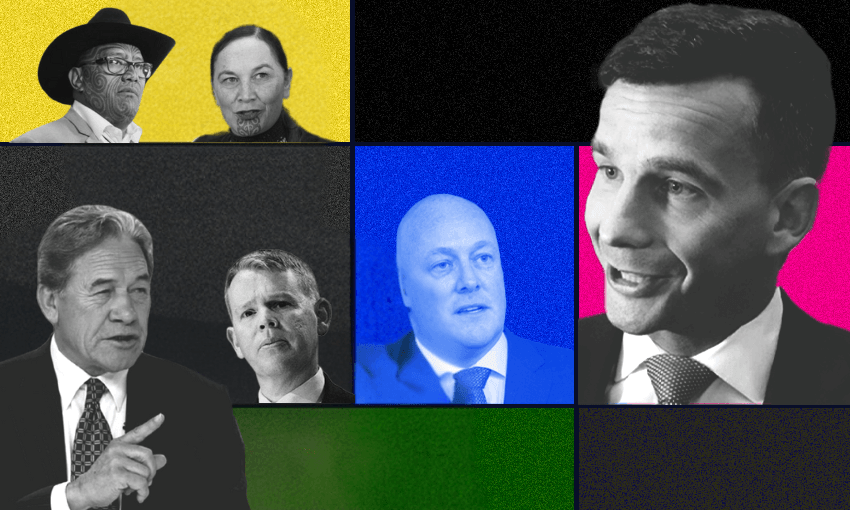

There has been a lot of “ruling out” going on in New Zealand politics lately. In the most recent outbreak, both the incoming and outgoing deputy prime ministers, Act’s David Seymour and NZ First’s Winston Peters, ruled out ever working with the Labour Party.

Seymour has also advised Labour to rule out working with Te Pāti Māori. Labour leader Chris Hipkins has engaged in some ruling out of his own, indicating he won’t work with Winston Peters again. Before the last election, National’s Christopher Luxon ruled out working with Te Pāti Māori.

And while the Greens haven’t yet formally ruled anyone out, co-leader Chlöe Swarbrick has said they could only work with National if it was prepared to “completely U-turn on their callous, cruel cuts to climate, to science, to people’s wellbeing”.

Much more of this and at next year’s general election New Zealanders will effectively face the same scenario they confronted routinely under electoral rules the country rejected over 30 years ago.

Under the old “first past the post” system, there was only ever one choice: voters could turn either left or right. Many hoped Mixed Member Proportional representation (MMP), used for the first time in 1996, would end this ideological forced choice.

Assuming enough voters supported parties other than National and Labour, the two traditional behemoths would have to negotiate rather than impose a governing agenda. Compromise between and within parties would be necessary.

Government by decree

By the 1990s, many had tired of doctrinaire governments happy to swing the policy pendulum from right to left and back again. In theory, MMP prised open a space for a centrist party that might be able to govern with either major player.

In a constitutional context where the political executive has been described as an “elected dictatorship”, part of the appeal of MMP was that it might constrain some of its worst excesses. Right now, that is starting to look a little naive.

For one thing, the current National-led coalition is behaving with the government-by-decree style associated with the radical, reforming Labour and National administrations of the 1980s and 1990s.

Most notably, the coalition has made greater use of parliamentary urgency than any other government in recent history, wielding its majority to avoid parliamentary and public scrutiny of contentious policies such as the Pay Equity Amendment Bill.

Second, in an ironic vindication of the anti-MMP campaign’s fears before the electoral system was changed – that small parties would exert outsized influence on government policy – the two smaller coalition partners appear to be doing just that.

It is neither possible nor desirable to quantify the degree of sway a smaller partner in a coalition should have. That is a political question, not a technical one.

But some of the administration’s most unpopular or contentious policies have emerged from Act (the Treaty principles bill and the Regulatory Standards legislation) and NZ First (tax breaks for heated tobacco products).

Rightly or wrongly, this has created a perception of weakness on the part of the National Party and the prime minister. Of greater concern, perhaps, is the risk the controversial changes Act and NZ First have managed to secure will erode – at least in some quarters – faith in the legitimacy of our electoral arrangements.

The centre cannot hold

Lastly, the party system seems to be settling into a two-bloc configuration: National/Act/NZ First on the right, and Labour/Greens/Te Pāti Māori on the left.

In both blocs, the two major parties sit closer to the centre than the smaller parties. True, NZ First has tried to brand itself as a moderate “commonsense” party, and has worked with both National and Labour, but that is not its position now.

In both blocs, too, the combined strength of the smaller parties is roughly half that of the major player. The Greens, Te Pāti Māori, NZ First and Act may be small, but they are not minor.

In effect, the absence of a genuinely moderate centre party has meant a return to the zero-sum politics of the pre-MMP era. It has also handed considerable leverage to smaller parties on both the left and right of the political spectrum.

Furthermore, if the combined two-party share of the vote captured by National and Labour continues to fall (as the latest polls show), and those parties have nowhere else to turn, small party influence will increase.

For some, of course, this may be a good thing. But to those with memories of the executive-centric, winner-takes-all politics of the 1980s and 1990s, it is starting to look all too familiar.

The re-emergence of a binary ideological choice might even suggest New Zealand – lacking the constitutional guardrails common in other democracies – needs to look beyond MMP for other ways to limit the power of its governments.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.