Will she or won’t she? Desley Simpson is still waiting to say whether she will run for the Auckland mayoralty in October.

Only 3.2% of The Spinoff’s readership supports us financially. We need to grow that to 4% this year to keep creating the work you love. Sign up to be a member today.

The first time I met Desley Simpson, she told me a story about herself. She’d been at a ball the week prior, dressed up to the nines in full glamour. When she was leaving, two rubbish collectors were making their way along the road, collecting and emptying bins into a truck. The deputy mayor, filled with goodwill and potentially bubbles and canapés, couldn’t help but to approach the two hi-vis-wearing men on their nightshift. In her dress, Simpson effusively thanked them for their services to the city.

When she told me the story, Simpson herself was in hi-vis. We were in a cage suspended from a crane that was slowly lowering us down to the final meters of the Central Interceptor tunnel, on the day of the final breakthrough – the completion of the 16.2km stretch. The pink hard hat and clear safety glasses didn’t look out of place on her head, somehow matching her pearl earrings. Towering next to her, Wayne Brown held onto the slightly wobbling cage. Down in the tunnel, Simpson climbed the mound of wet earth toward the boring machine and asked the miners if she could climb through it to see the other side. No, they told her, it was too dangerous.

In Auckland Council, Simpson holds a number of high-profile roles, deputy mayor of course but also chair of the Revenue, Expenditure and Value Committee and councillor for the Ōrākei Ward. But it’s the role she doesn’t have that is stirring attention. In January, speculation started in the media that Simpson was to stand for mayor of Auckland in the upcoming October elections. Her son had registered the domain DesleyforMayor.co.nz and rumours were circling that she was preparing to launch a mayoral bid. Simpson simply told the media that she had “not yet made a decision about what I intend to do this year“. At the moment, the domain redirects to her general website, desleysimpson.co.nz

Now it’s May. The election is five months away. Simpson is pacing her central city, 26th-floor office as she talks to me on the phone. It’s been almost an hour – an obscene amount of time for someone as busy as her to give to a journalist. She’s told me about her love of the city, her drive to make things better, her approach to advocacy and her “Italian style” close-knit family.

But will she be running for mayor? She won’t say. And before she says anything to the media, there will be a conversation with the current mayor. The rest of us can expect to know in early June. “I want the timing to be a timing that works for me,” she says, and that’s that.

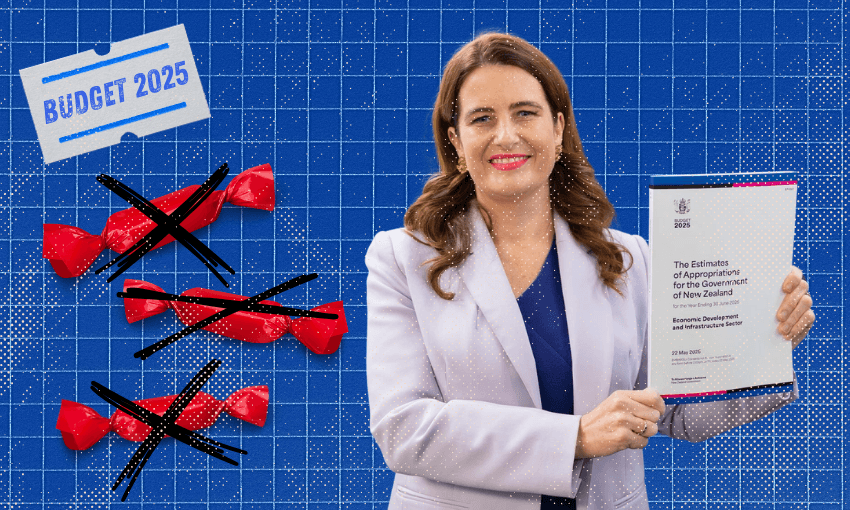

Auckland knows Simpson as the deputy who wears bright designer clothing, but also the deputy who fronted up with empathy and clear communication after the Auckland Anniversary floods in 2023, and again after Cyclone Gabrielle a few weeks later and again after flash floods that May. Back then, in the wake of Wayne Brown’s mistakes and dropped balls, people were asking “Why isn’t Desley Simpson the mayor?” Last year, Simpson said that she hadn’t yet stood for mayor because “I never thought anyone would vote for someone who looks like me”. For that article, she was photographed standing in front of her Porsche 911, even though the writer noted her reluctance. In the photo she’s smiling, though she’s crossed not only her arms but also her legs.

Simpson has had a gutsful of being judged by her style, a symbol, perhaps, of her birth into a wealthy, affluent Remuera family. When I ask how her generational wealth might affect her place in the city, she tells me it’s “sad” I’ve even asked the question and that every journalist asks it in one way or another. “Why should it matter whether I’m wealthy or not?” Her pause stretches out – up until now her sentences have been long and flowing. “Judge me on my performance, not what I look like, what car I drive, what clothes I wear, or how much money I’ve got in the bank. Does that make me better or worse?” She pauses again – the seconds tick. “It shouldn’t matter.”

But why does Simpson work so hard, when she could, if she wanted to, be a lady of leisure? Yes, it’s nice to dig a small hole in the ground and then chat over tiny croissants and tea afterwards, but most of the time council business is “dry and procedural” a councillor told me outside a Revenue and Expenditure Committee meeting that Simpson was chairing. Indeed the room had been discussing the possible procurement of new rubbish bins for nearly an hour, and there were still three or four hours to go on waste water, insurance renewal and building consent reviews.

Simpson says family drew her to politics. Her great, great uncle was Sir Henry Brett, the sixth mayor of Auckland in 1877, and her grandfather was James Donald, a long-serving member of the Auckland City Council before moving into government. But perhaps the greatest pull was from her father. For decades he asked her if she was interested in politics, but Simpson continuously rebuffed him. “Why did I say no?” she asks now. She thinks it was because she had young children and she’d seen some examples where politicians had got bad press, and then kids had been nasty at school. “I just didn’t want my children to be subjected to that”.

When her father was dying “badly” of bone cancer in December 2006, the last thing Simpson remembers him saying to her is “Are you sure you don’t want to go into local government politics, because I think you’d be really good”. The following October, Simpson had topped the poll for the Hobson Community Board, running on the Communities and Residents ticket. She quickly caught “the bug”. When the regional councils became the supercity in 2010, her ward became the Ōrākei Local Board, which she became councillor of in 2016. She was deputy chair, then chair, of the Finance and Performance Committee and has been “very successful in delivering the savings target”. She is proud of the savings and efficiencies she’s made in the role, and even though she knows this is an article about her, she asks if I could please include the fact that currently, only 35% of the council’s income comes from ratepayers, and that their debt is only about 17.1% of their assets. “I don’t want Auckland to think that we’re a nightmare financially, because we’re absolutely not,” she says.

At the start of May, Simpson and Ōrākei Local Board members turned the sod on the final section of Te Ara Ki Uta Ki Tai (Glen Innes to Tāmaki Drive shared path). Simpson drove a spade into the muddy ground near the edge of Whakatakata Bay off Ngapipi Road with bright pink sneakers. It’s a project she is proud of delivering. The cycling and walking path will eventually join Merton Road near the Glen Innes train station to the waterfront at Tāmaki Drive. The fourth and final section will be a 870m boardwalk along the coastline from Ōrākei bay to Whakatakata reserve.

As Simpson pointed out in her opening speech at the formalities, the whole project has been over a decade in the making and has survived major changes in central government. She’s “tickled pink” that the final part is under way. The officials that speak after her, minister for Auckland Simeon Brown, chair of Auckland Transport Richard Leggat, local board chair Scott Milne and Steve Mutton from New Zealand Transport Agency, allude to Simpson’s role in its survival. When the word “persistence” is thrown out, there’s a few chortles from the front row.

Later she tells me that securing funding from central government for this last leg of the project took “three goes”. This is the kind of thing she means when she talks about advocacy – which she does often. She knew that people in her ward wanted the project, she saw its value to her area and its neighbors for recreation and commuting and so she found a way to sell it. “You have to know what makes the relevant minister tick, what pushes their buttons and then you have to really advocate well,” she says. Sometimes she thinks about it all like a venn diagram. There’s what the local board or council want in one circle, what central government wants in another and what Aucklanders want in a third circle (though that could be the same circle as their local representatives). She finds the places where those circles overlap, and pushes to “get on and deliver that”.

What she isn’t is “one of those politicians that argue for the sake of it”. She sees a lot of politics that bring complaining, confrontation or opposition to the forefront. Simpson can imagine that someone else may have gone to the media to call Auckland Transport “disgraceful” after a refusal to fund a project to stir a bit of drama. “It’s sensational politics that the media love,” she says. “I struggle with that. That’s not my style. My style is to quietly find a solution.”

For Te Ara Ki Uta Ki Tai her style worked. She managed to get Simeon Brown (the ex-transport minister who loves cars) to agree to fund 51% of the final section. In his speech he said “it’s very important to finish what we started”, that the path “unlocks” one of the most beautiful parts of Auckland and that “it’s not taking lanes away from traffic, it’s adding another option”. One can’t help but wonder if before Brown thought these points, Simpson pointed them out to him.

At the turning of the sod a man in a grey suit asked me if I was a local. I told him I was there to observe Simpson, and that I was trying to write something beyond what clothes she wears as I knew it was a bug bear (and fair enough) of hers. “That’s always been a problem for Desley,” he said. He’d worked with her for a number of years on the board and had seen her work harder than anyone else he knew. As for her personal style, it may have got in the way a bit, but he respected her for “not changing herself”.

Earlier this year, scuffles in the media have seen Wayne Brown, who appointed her deputy mayor in 2022, saying “all she thinks about is how to help people buying their next Lamborghini” and then apologising. An article about him asking her to step down as deputy if she was to run was published, then retracted, by the New Zealand Herald. This, it seems, is the “sensational media” that Simpson prefers not to play into. When asked to provide comment for this article, Brown wrote a brief statement saying Simpson was a “natural choice” for deputy due to her background, and “I’ve appreciated the support she’s provided during this term.” Simpson prefers not to focus too much on Brown, generally saying that they’ve worked well together during the term.

For Simpson, being deputy mayor has been a job that is “seven days a week, 24 hours a day”. Sometimes four weeks go by without a day off and the days run out of hours. “I absolutely give it my all,” she says. Her reason? “That most wonderful feeling when you know you’ve made a difference. When you see that you’ve left your city in a better place than it was.”

There’s a pause on the line. Me in a small meeting room at one end, her in her high-rise office at the other. One can only assume she is wearing an outfit worthy of a detailed description in a lengthy profile. But she wouldn’t want to read that, she’s far too busy.