They’re made and spread quickly, cause intense harm and mostly target younger women and girls, but creating and sharing pornographic deepfakes is, in most cases, totally legal. Act MP Laura McClure’s member’s bill wants to change that.

Content warning: This piece discusses suicide and sexual exploitation.

The pictures were surprisingly easy to make. All she had to do was upload a photo of herself onto a website found through a quick search, and let it spew out AI-generated images of her naked in the bedroom, the bathroom, the kitchen – there was even a tool to make her appear more childlike. Her body may have been imagined, but for all intents and purposes, it was imagined to be her.

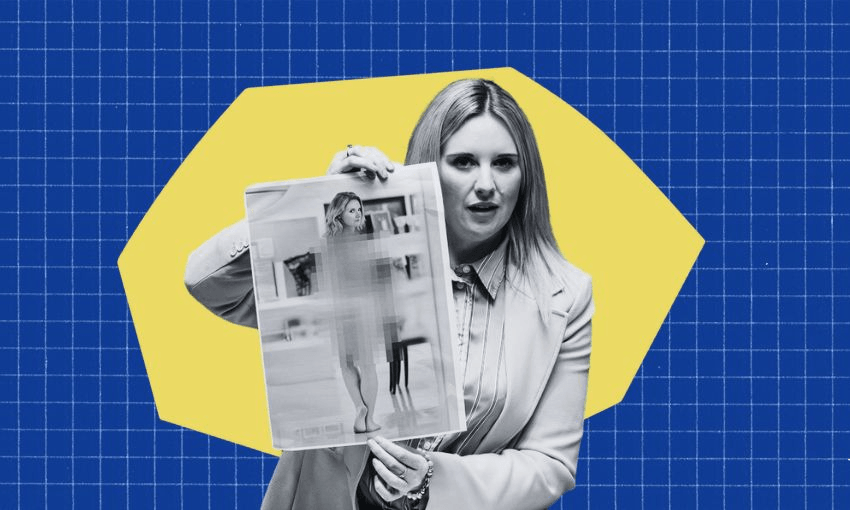

It was a first for parliament when Act MP Laura McClure presented a doctored image of herself nude to the House in mid-May, but according to Netsafe, these pornographic deepfakes are now popping up and ruining lives almost daily. They’re quick to make, cause incredible emotional damage and they mostly target younger women and girls, but they’re not illegal, and there’s no way of knowing exactly how many New Zealanders are being harmed by them.

A member’s bill drafted by McClure would criminalise the creation of these images by adding amendments to the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 and Crimes Act 1961 to expand the definition of “intimate visual recordings” to include those that have been synthesised. McClure told The Spinoff the bill was born from numerous discussions with parents, school teachers and advocates whose daughters and students had been impacted by pornographic deepfakes.

The stories McClure heard were deeply upsetting – in one instance, a 13-year-old girl had attempted suicide on school grounds after being deepfaked in this way. At a school in North Canterbury, 15 girls had explicit deepfaked images of themselves shared on social media. In one Auckland school, a group of 50 girls in the year 10 cohort were targets of this.

One teen girl of Muslim faith was deepfaked naked as a “joke”, McClure said. The experience was not only “deeply offensive” for the girl, but it had a significant impact on her relationship with her family. “It’s something that schools are really struggling to tackle, because there is a grey area in our legislation,” McClure said. “There is no real way that victims of this can get any justice and real support, because the support isn’t there when it’s not a crime.”

With near-daily calls being made to Netsafe about these images, chief online safety officer Sean Lyons told The Spinoff the fear they instil in targets is “huge”, and can be “emotionally and psychologically damaging in the very worst ways for many people”. The online safety organisation works with targets and perpetrators to remove this online content and impose civil sanctions (typically a fine) where possible, and while larger platforms such as Pornhub are typically responsive in these cases, others exist solely for the purpose of sharing these images.

“We know the amount of harm that these things cause is directly related to just how long it’s up there – just how long people perceive that people can see this really does amplify the harm that individuals feel,” Lyons said. The homespun logic that if you don’t take a risqué image of yourself, then you won’t be a victim of being seen in a sexually compromising position without your consent is no longer true, Lyons said – now, anyone can be a victim of image-based abuse.

In some ways, having a pornographic deepfake of yourself made and posted online can be far more damaging than if the image was real, lawyer Arran Hunt told The Spinoff. “You have no choice as to that image being created in the first place,” he said. “It’s completely out of your hands.”

Hunt has been long advocating for our laws to catch up with this technology because as it stands, no one has been successful in taking a deepfake case down a criminal legal pathway. It all comes down to the intention, Hunt said, and the creation of pornographic deepfakes is typically driven by desire for “financial gain, a laugh, peer pressure, attention – to cause harm is often not actually the reason they’re doing it”.

When the Harmful Digital Communications Act 2015 was amended in 2022 to include unauthorised posting of an intimate visual recording, Hunt was one of many submitters in the select committee process who suggested the definition of this material should include synthesised images. The suggestion didn’t make it past the submissions phase, and Hunt worries it will take the death of a “blonde white female” for our laws to catch up.

Hunt said the onus needs to be on the creator of the image, rather than the app or platform that generates it. “If Little Johnny is creating deepfakes of somebody else and it’s causing them harm, then Little Johnny should be facing the court,” Hunt said. “Not just that we’ll have a meeting with Little Johnny’s parents and hopefully he stops doing it because he’s a menace.”

McClure’s bill is a member’s bill, so it’s sitting in the biscuit tin, waiting for a chance to be plucked and introduced to parliament. After telling the Herald in May that he was not considering adopting it as a government bill, justice minister Paul Goldsmith will be meeting with McClure in July to discuss the bill. It’s been “frustrating” waiting for change, McClure said, but a meeting with the minister is a “positive step forward”.

“What I do think the government needs to consider is, do we want to put these preventions in place now while the issue is just emerging and starting to grow, or are we going to be reactive when a young girl takes her life?”