How a small medical practice caring for its working community led to the public health system we have today.

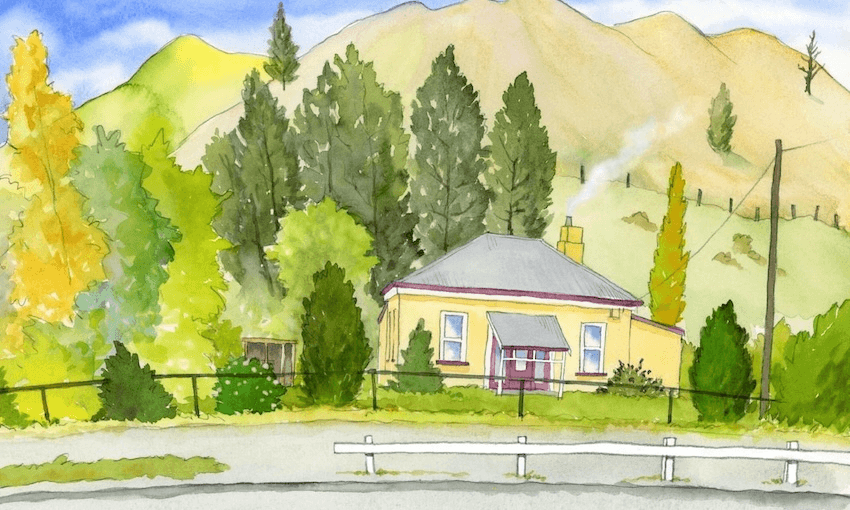

Illustrations by Bob Kerr

Doctor Gervan McMillan was a man in a hurry. He expected the trains in the shunting yards at the Waitaki dam construction site to give way to his car when he arrived to deal with a work accident. In an effort to employ as many men as possible, work on the dam was being done with wheelbarrows and shovels. Very little machinery was used and there were often accidents. Nine men died during the construction of the dam. Work over the cold fast- flowing river in a windy climate caused men to slip or be blown into the water. At least three were drowned.

Gervan and his wife Ethel McMillan had arrived in Kurow in 1929, just as work was starting on the construction of the dam 7 kms upriver. They may have been expecting a quiet and varied rural medical practice but within a couple of years the construction of the dam was employing more than 1,200 men. It was the middle of the great depression and unemployed people arrived from all over New Zealand hoping to find work.

As the depression got worse, more unemployed arrived than there were jobs. The McMillians modified an out building on their property and fitted it out with mattresses and blankets, so that newly-arrived unemployed men had somewhere to stay. Many of them had walked up the Waitaki valley from Ōamaru, some bringing their own shovel. They were often given a meal and clothing in return for gardening and chopping firewood.

They would then move on to camp at The Willows, on the banks of the Awakino Stream just below the dam, to wait until a job became available. At The Willows, families lived in tents and shacks made out of willow logs and flattened petrol tins and survived on rabbit stew. The hills on either side of the stream protected the squatters from the worst of the freezing westerly winds but these hills also shaded the valley. In winter, frosts lay on the ground for weeks. Local legend had it that “whiskey froze in the bottle and nappies hung like boards on the line”.

In his 1984 book Waitaki Damned, Gil Natusch, an engineer on the dam, described Dr McMillan: “He regarded himself as on call 24 hours a day, and without a surgery nurse he was willing to tackle anything from delivering babies to treating everybody’s ailments, extracting teeth, dealing with sickness and major accidents and emergency amputations. The ‘little Doctor’ is still remembered with respect and affection by those he served.”

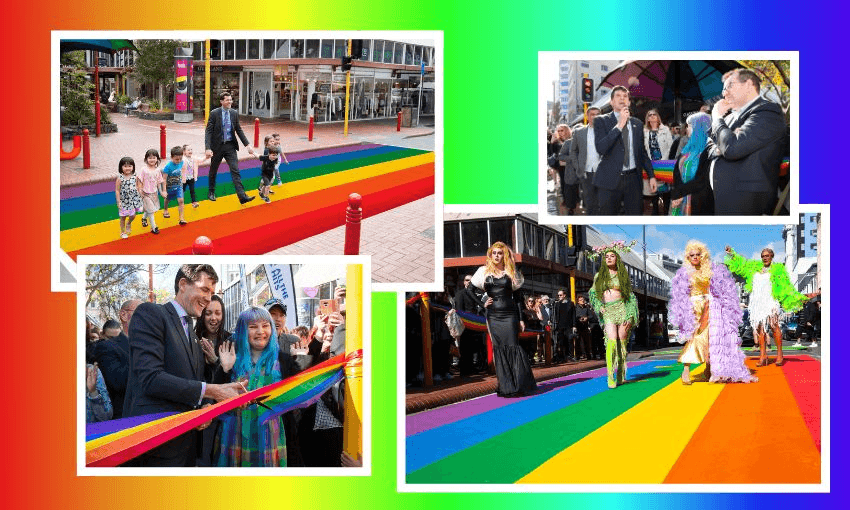

The current health minister, Simeon Brown, has said he doesn’t want public health doctors “leading advocacy campaigns”. He was supported by Act leader David Seymour who said he was “cheering on Simeon putting those muppets back in their box”. McMillan was a doctor who refused to be put in a box.

The Public Works Department, which was building the dam, and the local hospital board ran the Waitaki Medical Association. It was a co-operative medical insurance scheme. Workers on the dam paid four shillings and threepence per month for basic medical services. At a time when people paid for their own hospital care, and it cost nine shillings a day for a bed in Ōamaru hospital, this was a good deal.

The McMillans soon got to know the town’s Presbyterian minister Arnold Nordmeyer, the school principal Andrew Davidson, and Jerry Skinner, a unionist working on the dam. They would sit around the kitchen table in the doctor’s house and discuss how they could expand the services provided by the Waitaki Medical Association. They believed it could apply to the whole country. They summarised their ideas in six sentences:

A national health service should be free, they wrote, it must be complete and it must meet the needs of all the people.

- It must aim at the prevention of disease.

- It must make provision for income loss.

- It must provide all the facilities for the diagnosis and treatment of disease.

- It must be based on the provision of a family doctor for every person.

- The service must be based on the principle of the patient’s free choice of doctor.

- It must include the adequate provision for research in all matters relating to health.

McMillan took their ideas for a free medical service to the Labour Party conference in 1934. The paper he presented became party policy. It was opposed by the British Medical Association. Dr Eric Stubbs, representing the BMA wrote, “For those who by reason of deficient intelligence or deficient character are still unfortunately unable [to pay for their medical care] a small extension to the current system will be sufficient.”

With the sudden arrival of unemployed workers at the Willows and construction workers on the dam, Andrew Davidson’s Kurow school roll had jumped from 63 to 339 by 1932. His students spilled out into Nordmeyer’s church hall, the social hall and the totaliser building at the racecourse. It was a lively time in education, with Dr Clarence Beeby, the director of education, pressing for social and economic equality for every child regardless of academic ability, and what he called the child-centred school rather than the school-centred child.

Andrew Davidson’s first task with his pupils was often to provide them with warm clothing bought with money that “Nordy” had raised and to provide hot cocoa to warm them before school could begin. ”We were fired with a fervent desire to create a new society,” wrote Davidson in his memoir.

The dam was completed in 1934. Many of the workers moved west to the construction of the Homer Tunnel. In 1935, McMillan and Nordmeyer were elected to parliament in the new Labour government – McMillan in the seat of Dunedin West and Nordmeyer in Ōamaru. Jerry Skinner was elected as a Labour MP in the Motueka seat in 1938. Andrew Davidson left Kurow to become the principal of MacAndrew Road Intermediate School in Dunedin.

In parliament, Nordmeyer and Macmillan expanded their medical scheme into the Social Security Act of 1938, which combined a free hospital system with comprehensive welfare benefits. This is how the title page of the 1938 act summed it up:

“An Act to provide for the payment of superannuation benefits and of other benefits designed to safeguard the people of New Zealand from the disabilities arising from age, sickness, widowhood, orphanhood, unemployment, or other exceptional conditions; to provide a system whereby medical and hospital treatment will be made available to persons requiring such treatment; and further, to provide such other benefits as may be necessary to maintain and promote the health and general welfare of the community.”