Floods in Christchurch and Banks Peninsula earlier this month closed roads and damaged businesses. Shanti Mathias explores how local authorities have been preparing for extreme weather events, and whether it made any difference.

Between April 30 and May 1, Christchurch had its fourth-heaviest day of rainfall on record. More than 140mm fell over three days in unrelenting grey sheets.

In the city’s rivers, the water started to rise. By 4pm on Thursday, May 1, the Ōpāwaho/Heathcote River had burst its banks, with a rush of brown water sloshing over riverside terraces in Beckenham, making the roads unusable. A state of emergency was declared by Christchurch mayor Phil Mauger. Slips and surface flooding temporarily blocked all routes to Banks Peninsula. In Selwyn, paddocks became water features. Reporter Tim Brown, on RNZ, tried to figure out which holes of a golf course were underwater.

So far, so normal for storm events that have become increasingly common in Aotearoa, thanks to increasing temperatures and the climate crisis. For people who had to deal with the inconvenience of flooded businesses and power cuts, it’s hard to focus on the positives. But the flooding could have been much worse.

“The stormwater network performed very well around the peninsula,” says Tyrone Fields, the Banks Peninsula representative on Christchurch City Council. “Contractors have been working into the wee small hours to deal with slips and fallen trees.”

Worst hit was Little River, a Banks Peninsula settlement to Christchurch’s south-east, where water sloshed through the local pub. The town is low-lying and in a valley, next to Wairewa/Lake Forsyth. (Wairewa means “fast-rising water” in te reo, a sign that flooding has long been common in the area.) Little River has a flood working group that includes Ecan representation to look at improving resilience in the small community.

Wairewa and the neighbouring bigger lake, Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere, can quickly fill with water running off the surrounding hills. In floods, one option is to use diggers to open the water to the sea. Some residents told One News they would have liked the council to open Wairewa and Te Waihora to the sea to allow faster drainage and limit flooding. This requires diggers to push through sandbanks, dwarfed by the water around them. Given the amount of sediment in the lake and the tidal cycle, this doesn’t always work as intended; Te Waihora was instead opened after the flooding was over, on Tuesday May 6, and Wairewa on May 2.

“Maybe the channel would have closed over [due to sediment], but I can see how opening it would have been a good idea in terms of public confidence,” Fields says. The decision not to open the lakes earlier will be reviewed.

Investing creates resilience

In Christchurch, houses around Ōpāwaho have been flooded before, including in 2014 and 2017, requiring large clean-ups. Since then, the city council has spent more than $120m on flood management infrastructure.

Most prominent of these is Te Kuru, which includes wetlands, stormwater storage and filtration in the Ōpāwaho’s upper catchment. “Despite getting more than 140mm of rain, we managed to avoid some of the worst impacts of flooding that we’ve seen all too often in the past, before we started to upgrade our system in earnest. There was a notable difference in the scale of flooding in areas like Beckenham and Woolston where we’ve historically seen properties and homes flooded,” said city mayor Phil Mauger in a press release.

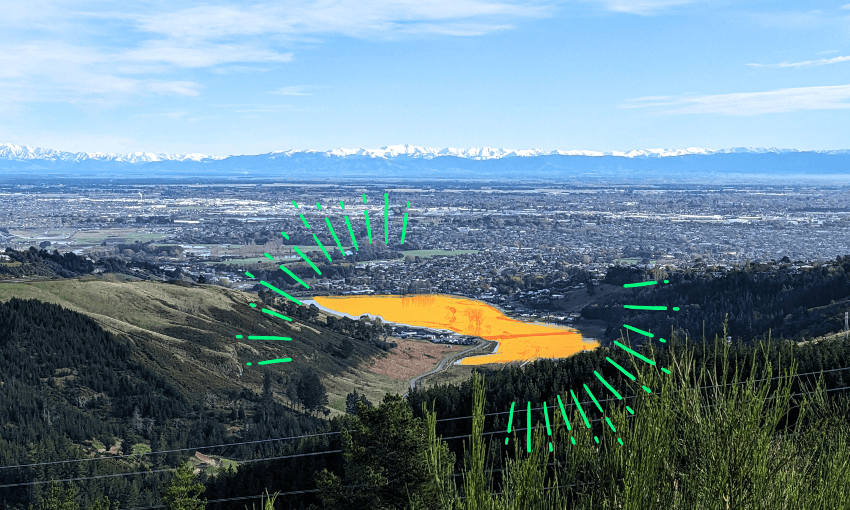

In heavy rain, gates around these stormwater basins can be closed, meaning the water doesn’t enter the river all at once. Te Kuru can hold more than a million cubic metres of water, which can then slowly be released. From the Port Hills above – from where all the water is draining – Te Kuru looks like a temporary lake, brown and shiny, meaning that people’s houses aren’t in the way of the river.

“Our stormwater basins are designed to fill and eventually overflow, and performed as expected during the event,” says Tim Drennan, the city council’s acting head of three waters. Stormwater infrastructure on roads has been improved too. “In most parts of the city our roads have been designed as secondary flow paths for stormwater,” Drennan says. During the May 1 event, water on roads was an intended outcome. “As expected, some of our roads flooded with water – this is better than houses or property flooding.”

There are other wetland restoration and flood mitigation measures being put in place around Christchurch. The “red zone” around the city’s Avon River, where earthquake and flood risk was deemed too high to rebuild after the 2011 earthquakes, has included more wetlands. The current long term plan dedicates $42m to water detention and treatment in the Avon/Ōtākaro catchment. Overall, the city council has $349m going to various flooding management programmes in the plan.

Under the changing realities of a warming climate, responding to floods and sea level rise becomes more important. “We are in this zeitgeist of climate change, and planning needs to happen now,” Fields says.

Vicky Southworth, who represents Christchurch South on ECan, agrees. “There are lots of difficulties ahead, especially in areas where the regional council has identified hazards but there are a lot of homes.” Without adaptation legislation from the government, those hazard maps can impact people’s insurance or ability to sell their homes. ECan can provide flooding hazard assessments for individual properties, which may be a requirement to get a building consent.

Christchurch City Council conducts hydraulic modelling too, and data about where water fell and accumulated on May 1 will be used to improve future models.

Room for the river

One concept councils around the country are increasingly applying to flood management is the idea of “room for the river”. A framework used around the world, this differs from traditional flood management. Instead of dealing with flooding on a case-by-case basis – this area keeps flooding? Add a higher stopbank! – room for the river considers rivers a whole system. Stopbanks, for example, are effective ways to prevent one particular area from flooding, but they mean the river flow gets faster, potentially causing more destruction downstream.

“Rivers have natural flood processes,” says Jon Tunnicliffe, an associate professor at the University of Auckland who researches river dynamics. “When we understand how much room the river needs, we can set boundaries appropriately.”

The Canterbury Plains, with huge amounts of water travelling from the Southern Alps to the ocean, often in large braided rivers, are prime candidates for this framework to be applied. “Braided rivers have a spectacular array of paleochannels which are activated when the flood comes through,” Tunnicliffe says, referring to river or stream channels that no longer carry water.

Christchurch’s rivers look very different now to how they did before European settlement. Essentially, much of the city has been built on floodplains or wetlands. As more and more houses were placed on the land, the way rivers shift courses and flood became less acceptable; stopbanks and canals were used to make rivers like the Waimakariri straighter and have only a single course, instead of curling and splitting. “The more flow is constrained, the deeper and narrower the channel, the more intense the erosion,” Tunnicliffe says. But there’s another way. “If we accept that inundation [flooding] is going to happen and have designated places for it, we can protect infrastructure like roads and bridges.”

One lesson from the room for the river framework is that changes made in the headwaters of a river, the point at which it starts, can make a big difference. Having some paddocks that are designed to flood, or stormwater containing wetland designs like Te Kuru, can make a big difference. Water can be released slowly into a river, instead of all at once.

Designing the space around rivers with the expectation that they will flood at times has other benefits, too. “If people are safe, having the flood on a greater area of land tops up the groundwater table,” says Southworth. As well as floods, climate change will bring droughts. “If groundwater is properly managed, it can serve a role when it’s dry.”

Environment Canterbury and Christchurch City Council are increasingly applying the room for the river framework to its work around Canterbury watersheds. Around the Rangitata River, where a 2019 flood made the river flow 35 times faster than usual and broke the banks in five places, flood recovery has included reinforcing stopbanks. But some native planting and wetland restoration has been part of the process too. “It’s not logically possible to keep doing the same thing as the storms get bigger and the sea level comes up,” Southworth says.

While there isn’t money for every action – especially when that might require people to move out of their homes – the biggest lesson from the recent flooding is that preparation can make a difference. “Big events happen,” says Fields. “We can’t solve every problem, but we can build resilience.”