The Commerce Commission has received more than 100 enquiries about them this year alone, but the fake storefronts continue to operate. Madeleine Chapman reports.

Only 3.2% of The Spinoff’s readership supports us financially. We need to grow that to 4% this year to keep creating the work you love. Please sign up to be a member today.

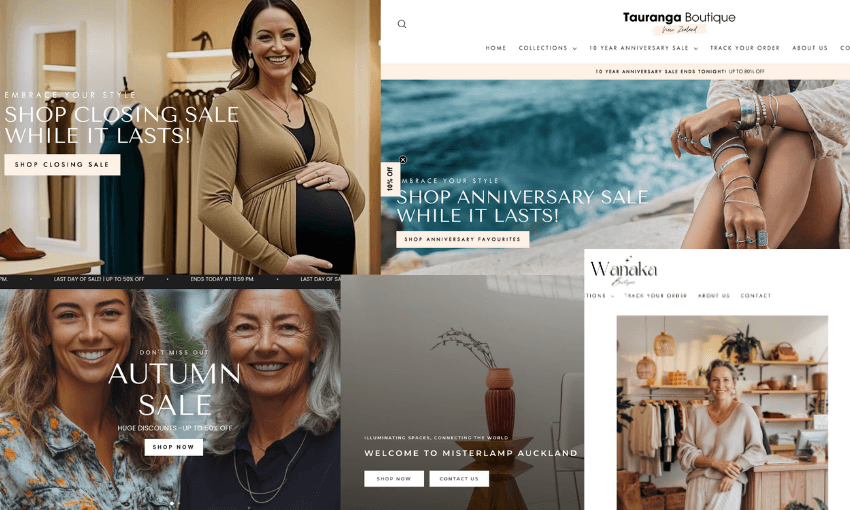

At a glance, it looks like any other clothing website. There’s a banner along the top for a “clearance sale” which ends at 11.59pm. Scroll down and a grid filled with “bestsellers” appears, showing blouses, shoes, dresses and more being modelled by real people and featuring heavily discounted prices (usually half price).

And below that, the story behind the brand. “From the heart of lovely Tauranga” is the heading. “Driven by their love for the coast and a passion for beach-inspired collections, sisters Zoey and Sarah founded Tauranga Boutique in 2018.”

There are multiple collections, a promise of free shipping, and a prompt to “join our family” by signing up to receive VIP perks and new collection sneak peeks. There’s an “About us” page and FAQs (like “are your products sustainably sourced?” The answer: “Absolutely!”) and a contact form.

Tauranga Boutique’s website looks like any other small retail business making the move from brick and mortar to online.

Except it’s not real. And neither are sisters Zoey and Sarah.

Vicki Kenny is not opposed to overseas manufacturing. A former clothing designer who knows the costly realities of “Made in New Zealand”, Kenny assumes most local businesses will source materials or whole products from overseas. But she still likes to support local distributors where she can. So when a Tauranga Boutique ad for an animal print dress appeared on her Instagram feed, she clicked. “I was busy trying to organise myself for a holiday to South Africa, and I thought ‘oh, that would be a really good dress to wear’,” she says.

She ordered it, but three weeks later it hadn’t arrived at her Auckland home. “I started thinking it was coming from Asia. You know, it wasn’t local at all, but I didn’t really think too much about it.” She went on holiday for another three weeks and when she returned, her dress had arrived. Advertised on the Tauranga Boutique website as a New Zealand design made with cotton, the real thing was anything but. “It was really badly made,” Kenny recalls. “The sleeve had a top seam going down the front of my arm. No one does that, it’s just not what you do. The material was clearly polyester, but a really awful one that was like plastic, like it makes a noise when you put your fingers on it. No label on it, no care instructions, clearly not from New Zealand.”

So why did Kenny initially think her dress would be coming from within the country? Well, the name, for one. The “history” detailing Zoey and Sarah’s love of the beach and commitment to the area.

Disappointed, Kenny emailed “Zoey and Sarah” requesting a return and refund. On the Tauranga Boutique website, its returns policy states items can be returned within 90 days so long as they are intact and the buyer pays the return shipping costs.

In response to her email, “Zoey” said, “We understand you’re considering a return, and of course, we’re here to help! Before you decide, we want to make sure you’re fully aware of the high costs involved:

Return shipping: $35–$80 NZD

Customs fees: $29–$59 NZD”

This would put the possible cost of returning a $79 dress (weighing <1kg) as high as $139.

Helpfully, Zoey went on to suggest some alternatives: either a 25% refund or a 50% store credit.

“Most customers find these options much more valuable and stress-free than dealing with return fees and long processing times.”

Kenny chose to swallow the cost of the dress, which she couldn’t wear, and set out to warn other local consumers of stores like Tauranga Boutique. “Well, clearly I’m not going to get my money back, which is not really the end of the world, but it is the end of the world to a lot of people. That is a lot of money, and that sort of just got me on the crusade.”

As soon as she posted on Tiktok about her experience, Kenny’s videos received hundreds of comments from women who had the same experience with similar “stores”. Such boutique local offerings included Milas Auckland, Raglan Bay Boutique, Ivory Auckland, Pure Auckland, Kiwi Boutique and Wanaka Boutique.

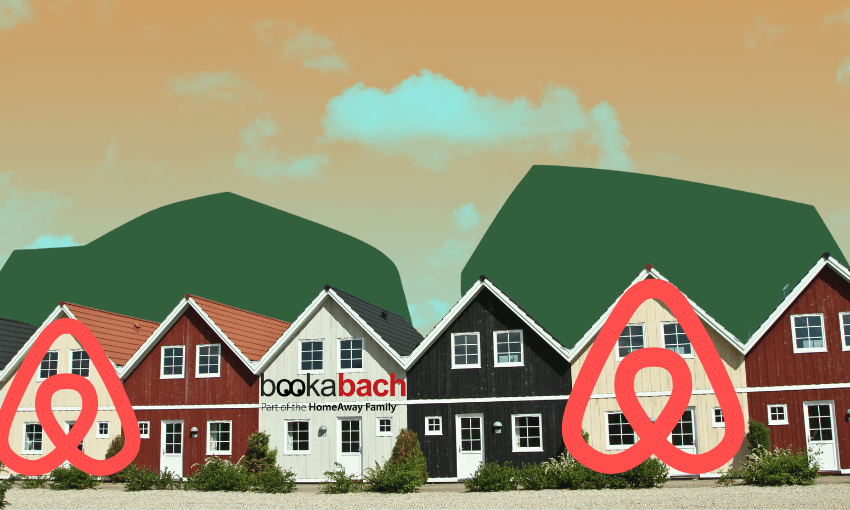

Drop-shipping is not a new concept in New Zealand, and has spread to all corners of the marketplace. Search for any generic item on Trade Me – billed as the home of the everyday seller – and the majority of the results will be dozens (often hundreds) of identical images, all being offered by different companies for virtually the same price. None are being sold by an individual, rather they’re companies advertising a vast range of goods that will then be ordered from another budget site like AliExpress or Temu.

For example, a Trade Me search for “iPhone charger” returns 5,242 results. But when filtered by “used only”, that number plummets to 48 iPhone chargers (or similar) being sold by individuals in New Zealand.

Where these new stores stand out is in their surface-level sophistication. Almost all will feature images of a fake storefront, suggesting there’s a physical store somewhere in New Zealand. Most will have an image of a woman or a couple which are AI-generated but at first glance appear to be real. Many will list “opening hours” as if they’re a regular store, but those are apparently just the hours that “customer service” (read: email) is available. Almost all of them don’t have an address or phone number.

Misterlamp Auckland did, however. The lamp seller’s website looks as normal as any other online store. The products are varied and cheap, but not so cheap as to seem fake (some lamps are as pricey as $2,000). The website lists “Opening hours”, with Saturday and Sunday closed. Unlike others, it lists an Auckland landline number. Call that number, however, and it’s disconnected.

An email to the info account asking where the lamps are made and who designs them received the following response:

“Hello Madeleine,

Thank you for reaching out and for your interest in our lamps! We take great pride in both the craftsmanship and design of our products.

Our lamps are made in multiple warehouses, each dedicated to maintaining high standards of quality and design. We collaborate with a variety of talented designers who bring unique perspectives and styles to our collections.

Thank you again for considering us for your article!

Best regards,

Sofia from the Misterlamp Team”

Who is Sofia? No one knows. But on first glance, Misterlamp Auckland appears to have a human presence behind it. Misterlamp claims to have four “web stores” in four countries, each named after the capital city (which Auckland is not). The parent company is registered in the UK but has had complaints from customers in Germany regarding false advertising and faulty products, then exorbitant fees to return the product to a China warehouse.

Is it a scam if the product is real?

Across dozens of posts in the past 12 months, many “boutique” stores have been accused of being “scams” by New Zealand social media users. “Scammer!! Watch out guys this lady is not a local in Wanaka closing down her shop,” reads one community Facebook post from March, warning shoppers about Wanaka Boutique. A number of commenters said they too were disappointed that they had been duped, but were surprised a product showed up at all, albeit of much lesser quality than advertised.

One commenter said they were convinced of a store’s legitimacy because of AfterPay being available. Surely a dodgy company wouldn’t be allowed to be registered with Afterpay? Wanaka Boutique advertises payment options from all major credit cards, Paypal, Apple Pay and Afterpay.

A spokesperson for Afterpay did not address questions relating to these fake “local” stores specifically, but Wānaka Boutique is a registered merchant. As for dispute resolution? “For Afterpay orders with a legitimate merchant, customers are encouraged to first contact the merchant to manage refunds or returns and then raise a dispute via the Afterpay App if direct contact with a legitimate merchant has not been effective,” they said.

What can be done?

The likelihood of being scammed online, or at the very least receiving a product that’s worse than you expected, seems to increase with every passing year. It has been well-documented that Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram, where these companies advertise heavily) does little, if anything, to combat scam ads.

For now, the suggestions from the likes of the National Cyber Security Centre and Retail NZ are for New Zealanders to simply keep reporting companies they believe are misleading customers, and be wary of social media advertising. There are suggestions to check the Companies Register or a domain hub for legitimacy, or monitor addresses and phone numbers – simple enough actions that would likely reveal a suspect website but that few consumers are likely to be diligent about.

Under the Fair Trading Act, traders in New Zealand are required to provide true information, meaning customers who feel misled by an online store’s claims about products, services or “story” can make a complaint to the Commerce Commission, who may investigate.

A spokesperson for the Commerce Commission told The Spinoff that it had received 107 “enquiries” about “these types of websites”, with 28 relating to Tauranga Boutique specifically.

“Any behaviour or marketing that misleads consumers is of concern to the Commission and could be a breach of the Fair Trading Act,” they said. The commission did not say whether it had opened an investigation.

The list of potentially misleading stores that Kenny and her followers have compiled is long, though some of the websites have recently been deactivated. Some domains change names after too many complaints or negative reviews, disappearing for a while only to reappear with a near identical website and a different city tagline. And once an ad has garnered a click-through on any platform, they’ll appear virtually everywhere.

Having visited the website of Misterlamp Auckland once in researching this story, their ads began appearing within NZ Herald articles, on Facebook, and even as a full page takeover ad on Stuff. Still the same business, still not actually based in Auckland.

Despite the many “enquiries” to the Commerce Commission, Tauranga Boutique is still operating. And guess what, there’s a 10-year anniversary sale on. But get in quick, it ends tonight.