A forensic tent on the morning school run. Gang tattoos in the sauna at the local pool. ‘Otai and prayers at the Saturday market. A young father reflects on what it really means to raise a family in Māngere.

It’s a cold and dark Thursday morning as I pull out of my driveway. My working-class neighbourhood of Māngere is already abuzz with the sounds of life: wheels turning on the wet road, children chatting playfully as they walk to school, caffeine-desperate patrons sitting in idle queues at the McDonald’s drive-thru.

I exit the roundabout on Bader Drive and immediately notice something odd. The main bus stop outside Māngere Town Centre – usually full of morning commuters – is cordoned off with white tape. “Police emergency” is splayed across it in bold, red capital letters. Behind it, a large blue police forensic tent stands in the middle of the road. I see a forensic photographer dressed in white overalls and a blue mask taking photos as a grey-blue dawn breaks. My heart sinks as I immediately think the worst; someone has died just metres from my house, again.

Sadness overcomes me as I think of my young son, strapped in his high chair eating breakfast just a stone’s throw away from where this has happened. Is this the kind of thing I want him seeing on his way to school? Is this our new normal now we live in South Auckland? I also think about whoever has been hurt. I wonder what happened to them and why. Do they have a family? Where were the security guards who were put at the bus stop after someone was killed there a couple of years ago?

As I drive north over Māngere Bridge, I glance left to the Manukau Harbour, desperate for the ocean to provide a sense of calm. I try to think of which song to play to alleviate my anxieties, but nothing feels right. Most of my commute to work is spent pondering what challenges my colleagues might have dealt with this morning. Maybe an unwilling toddler, a flat battery, or being stuck in traffic. However, I’m almost certain none of them had to bear witness to a scene like the one I did. This is no fault of their own, but a mixture of chance, environment and circumstance.

Later in the morning, I find a news report about the incident. Thankfully, it was a serious assault, not a homicide. Still, that does little to appease my reignited apprehensions about living in Māngere. I’m grateful for the benefits we get living here, but I’m also not ignorant to the realities of life in a lower socioeconomic suburb.

The next day – with almost uncanny timing – Jayden Cook will be sentenced to life imprisonment for the senseless murder of Talini Manu, also known as Billy Salapo, at the exact same bus stop in October 2023. In the 18 months since we moved to Māngere, a number of serious incidents have taken place in close proximity to our home. In March of 2024, a ram raid was carried out at the town centre. Earlier last month, there was a suspected gang-linked arson attack at a nearby funeral home. Last year, there was an unexplained death and a shooting on a street just down the road from my house. Just a month before that, a room with children inside it was shot at.

A lot of these events are at the more severe end of the criminal spectrum. While I don’t want to catastrophise, the sheer number of incidents makes me wonder if things are only going to get worse in neighbourhoods like ours.

Having lived in state houses, a caravan park, and areas considered “rough” by some, I’ve become familiar with the realities of life in a lower socioeconomic neighbourhood. While I have mostly had positive experiences in these areas, I am acutely aware of the complex challenges many in these communities face every day. Poverty, addiction, violence, gangs, crime and broken families are all challenges I’ve seen affect many in similar areas, often in deeply interconnected ways. But for most of those who were raised in these situations, it is simply everyday life.

From a young age, the normalisation of these circumstances skewed my perspective on what a “typical” life was. Growing up, I thought it was normal to live paycheck to paycheck, have a shitty car, or depend on bread and butter as a space filler with every meal. Many of the adults in my life had done time, hustled to get by, or operated outside the law in some way. However, as a father in my 30s (just) who has experienced life in both the lower and upper middle class, I like to think I now have a broader view of society and what constitutes a “normal” life. Initially, this dual experience helped to alleviate some of my unease about purchasing a property in an area I knew would have its issues.

When my fiancée and I were deciding where to buy, our options were limited because of our budget. Like many looking to purchase a home in the country’s largest and most expensive city, our preference was to be as central as possible. Eventually, we settled on a property in Māngere – a suburb located in the northern part of South Auckland.

Our house is one of two recent developments on a block otherwise filled mostly with Kāinga Ora housing, so we sort of stand out like sore thumbs at the moment. However, the inevitable – albeit slow – gentrification of Māngere is under way. Redevelopment of the massive state housing stock is in progress, which will eventually help us blend in a bit more.

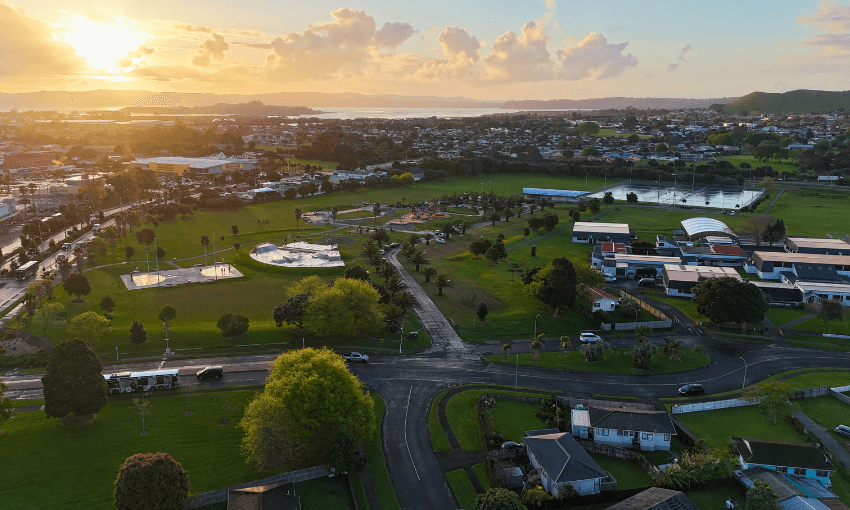

Besides the property itself, much of the appeal was its location. With no traffic, it’s just over a 20-minute drive to the city, and 10 minutes to the airport. We have close access to two major motorways and there are great local facilities including a pool and leisure centre, two supermarkets, Auckland’s fifth-best mall, public transport, parks, a million-dollar playground, schools (including one with the top NCEA pass rates in the country), doctors, pharmacies, an arts centre, a cultural centre, a birthing centre, and even a major tertiary institute all within a five-minute walk. The local takeaway stores are cheap and generous, most people say hello to you when you’re walking down the road, and there’s a vibrant local community with something always happening – I don’t think even those living in Herne Bay could say the same.

On the other hand, the raft of social issues impacting our community is clear to see. Almost every week, some sort of domestic incident is happening within earshot of our house. Just the other day, I saw a child who couldn’t have been older than 12 vaping on the side of the road. I’ve seen similar aged children at drug houses trying to tick up some weed. I’ve witnessed fist fights outside the supermarket and watched someone nonchalantly steal from the same supermarket (the checkout operator told me it happens almost every day and that just the day before, a shoplifter pulled a knife on the security guard when he tried to intervene). I’ve seen a kid getting a hiding in a car and once saw a guy start smoking weed from a can on a park bench in front of children playing basketball. I’ve even heard stories about a lady smoking from a meth pipe on the bleachers at the local pools.

Most weekends, I take my son to those pools for a swim (which is conveniently free across South Auckland). Just recently, I went there for a sauna after an intense basketball game. When I walked in, I was met by at least half a dozen burly men with electronic monitoring devices strapped to their ankles, all sporting some sort of gang-related tattoos. They were chatting about their recent lags, the “foul as” gang history of Māngere and more contemporary gang issues. As fascinating as it was to hear, it was equally discomforting.

I half-joked to my fiancée the other day that perhaps we should move to a more affluent suburb – somewhere these issues don’t exist, somewhere this sort of stuff doesn’t happen so frequently. I say half-joke, mostly because we can’t afford to move somewhere else right now, but also partly because I genuinely wonder if life would be easier in another suburb.

According to my father, my family sold our home in Mount Roskill when I was four so I wouldn’t be raised in the “hood” – although my uncle reckons my dad was just chasing some sort of financial gain. Whatever the reason, we moved to Whangaparāoa, a predominantly Pākehā area located about 40 minutes away from the city centre. It was here that I spent most of my childhood and I loved it.

While eventually moving out of Māngere is an option my fiancée and I often speak about seriously, we are both aware that doing so would have downsides as well as benefits. Despite its blemishes, I love living in Māngere and am very happy this is where we landed. I do hold very real fears about how this environment will impact our lives and that of our young son, but I also don’t want to let the negatives get the best of us.

A trip to the bustling Saturday market is often a highlight of my week. The ladies at my usual food truck stop always greet me with a smile as they take my order for a steak, egg and onion roll. I happily fork out $10 for the best otai I’ve ever had – especially since the guy there held my hand and prayed for me and my family after he found out my son was in hospital. The lamb buns alone are worth going for.

Whenever I can get to the local basketball court, it’s always full of friendly players keen for a competitive game. Everyone shakes your hand and introduces themselves. The playground is usually full of laughter. Quite often, the rhythmic beats of island drums, fob jams being played through sirens, and the hovering of the police helicopter provide the perfect background score for the melting pot that is Māngere.

I recently went to grab some Chinese takeaways for dinner and came back in a state of disbelief at the scenes I had just witnessed. Outside the store was a man in a get-up akin to a Slash outfit, playing guitar and singing the 1970s heavy metal ballad ‘The Temple of the King’ by Rainbow. There were half-cut streeties outside the liquor store offering friendly greetings to any passerby. Old men flooded the TAB as young kids sat in their cars, patiently waiting for their Friday night takeout. There was so much life in one little corner of our neighbourhood. It was a trip in every sense of the word.

Part of me doesn’t want my son to grow up here because of the fears I have about how he might be influenced by this environment. The other part of me would love for him to be exposed to it all – the rich and vibrant tapestry of cultures and people, the sense of community, and the defiance from those who live here to not allow the negative aspects of life in Māngere to define it.

I feel I have no choice but to embrace the realities of life in the 275 – the good, the bad and the ugly. I am proud to tell people I live in Māngere and I am excited to be a part of whatever the future holds for this community. Māngere is not perfect, but it’s honest. It shows you everything: the pain, the promise, the people.