New figures show a softening labour market, rising hardship for Māori and Pacific workers, and warning signs from the Reserve Bank, writes Catherine McGregor in today’s extract from The Bulletin.

To receive The Bulletin in full each weekday, sign up here.

Jobless rate holds steady, surprising economists

New Zealand’s unemployment rate remained unchanged at 5.1% in the March 2025 quarter – a headline figure that isn’t quite as reassuring as it seems. The latest Stats NZ release shows that the number of unemployed people has held steady at around 156,000, surprising economists who expected a modest rise. But as Kiwibank’s Jarrod Kerr notes, “It looked to be a little better than expected … but it wasn’t. Workers may not be losing their jobs, but many are losing valuable hours.” Full time jobs fell by 45,000 over the year, while part-time employment rose by 25,000. Hours worked fell 2.9% annually, and underutilisation – which captures people wanting more work – rose to 12.3%.

The labour force participation rate also dipped slightly to 70.8%, its lowest level since June 2020. While “employment” includes anyone working at least one hour a week, “labour force participation” reflects how many working-age people are actively working or looking for work – and its decline suggests a portion of the population is simply giving up.

Unemployment as policy tool

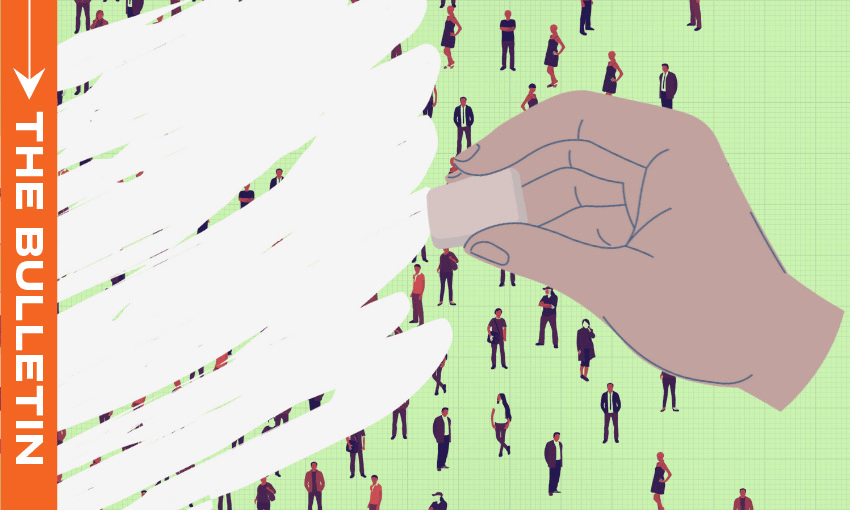

In a sharply worded column for The Spinoff this morning, commentator Max Rashbrooke describes the latest data as a grim reminder that New Zealand continues to treat unemployment as its main weapon against inflation. “We dealt with the post-pandemic inflation spike by the simple expedient of putting tens of thousands of people out of work,” he writes. The approach, born of the 1980s-era doctrine of inflation targeting, has seen the Reserve Bank hike interest rates to curb demand – and in turn push firms to cut back on staff.

Rashbrooke questions the fairness and effectiveness of this strategy, especially given mounting evidence that corporate profits – not just government spending – were a major driver of inflation. He also points to the human cost: “Unemployment has a much, much larger negative effect on people’s wellbeing than does inflation.”

And unlike most countries, New Zealand still lacks a social insurance scheme to cushion job losses, exacerbating the financial pain. Unemployed New Zealanders “often end up in positions much worse than the ones from which they were let go”, Rashbrooke writes, with a Motu study finding that people made redundant are, even five years on, earning on average one-fifth less than their peers. “The damage that ripples out from this surge in unemployment … will be felt for years to come.”

Read Max Rashbrooke’s column here

Disparities worsen for Māori and Pacific workers

The pain of job loss is not evenly distributed. While the overall rate may have peaked, Māori and Pacific unemployment continues to rise. Māori unemployment hit 10.5%, up from 9.7% in the December 2024 quarter. For Pacific people, it reached 10.8% – more than double the national rate and up from 10.5% in the December quarter, Pacific Media Network’s ‘Alakihihifo Vailala reports. Labour MP Carmel Sepuloni called the figures “shameful”, blaming cuts to public services and infrastructure projects which disproportionately affect industries where Māori and Pacific people are heavily employed. Last November Sepuloni’s colleague Barbara Edmonds said there were 12,000 fewer construction roles than when Labour left office in 2023, and 12,000 fewer in the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector.

Trade threats add to economic headwinds

Compounding the domestic challenges is global instability. The Reserve Bank’s six-monthly Financial Stability Report, also released yesterday, warned that Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs pose a “material risk” to New Zealand’s economy. While some exporters may benefit in the short term, sectors like meat, seafood and wine face “severe” disruption, Newsroom’s Jonathan Milne reports. If NZ exporters cut prices to absorb the 10% tariff, the result could be a loss of around 0.2% of GDP, the bank said.

More concerning is the broader economic drag from disrupted global supply chains and falling demand in major export markets. The bank “paints a picture of an economic slowdown hurting heavily indebted households and businesses – so that would most likely be combated with lower interest rates”, Milne writes. The next OCR announcement is expected on May 28.

More reading from The Spinoff: