The associate education minister has appealed for mayors’ support on improving school attendance. But should it really be part of their job, asks Catherine McGregor in today’s extract from The Bulletin.

To receive The Bulletin in full each weekday, sign up here.

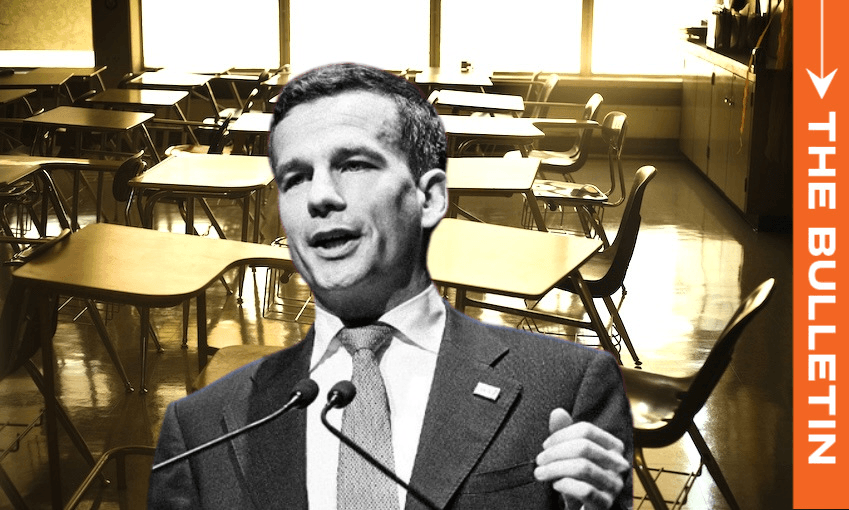

Mayors unimpressed by Seymour’s call to arms

Associate education minister David Seymour’s latest truancy push has landed awkwardly with local government leaders. In letters sent to all 78 mayors, Seymour asked them to champion school attendance in their communities, encouraging them to “lead a conversation with your community” on keeping kids in school.

As The Post’s Anna Whyte reports, a number of mayors have noted the request contradicts the government’s own messaging that councils should stick to core services like roads and water. “It’s a bit rich,” said Christchurch mayor Phil Mauger. “Nek minnit, I’ll be out cooking school lunches.” Seymour appeared unfazed, saying he was surprised mayors didn’t “put more of a smile on it” when asked to help their communities, especially given the upcoming local elections.

What the numbers actually tell us

Behind the back-and-forth is a complex picture of school attendance. The government has set a target for 80% of students to attend school more than 90% of the time by 2030. At present, just 58.1% of students meet that bar – up from 53% in 2023, but still well below pre-Covid levels.

This measure of “regular attendance” is widely used, yet controversial, as it makes no distinction between justified absences (such as illness or bereavement) and truancy. Last year Papatoetoe High principal Vaughan Couillault told The Spinoff it was a “binary” statistic that failed to reflect context. “It covers people in hospital, it covers funerals, it covers everything.” Daily all-of-school attendance rates – typically over 80% – offer a more nuanced view, but don’t feature as prominently in headlines.

Action plans and accountability measures

The government has rolled out a multi-pronged strategy to address the attendance issue. A daily attendance dashboard is up and running, and the government last year launched a public awareness campaign and updated its health advice for parents. More significantly, a Stepped Attendance Response (STAR) system will be mandatory for schools from 2026, escalating interventions based on days missed.

After 15 days’ absence, prosecution of parents may be considered – though Seymour has said fines would only apply to those with the ability to pay. This prospect worries many principals, who say punitive approaches are likely to backfire. “Fining them $50 a day or whatever just takes food out of the kids’ mouths,” said Couillault. Others argue the underlying causes – poverty, health, housing – require support, not penalties. “You’ve got to get alongside [families] and understand the issues, said NZEI president Mark Potter.

The silent surge in stand-downs

Alongside concerns about absenteeism is a quieter trend: the rising number of students being formally stood down from school. Unlike suspensions, stand-downs are short-term removals – up to five days – and are often used as a circuit breaker for behavioural issues. Their use has surged since Covid, with over 30,000 stand-downs in 2023, a 35% rise since 2019. “Assuming a five-day stand-down each time, that’s 153,510 school days lost,” notes economist Cameron Bagrie, writing yesterday in BusinessDesk (paywalled).

Could the numbers be entirely due to worsening student behaviour? Bagrie isn’t so sure. “Are stand-downs still being used for the right reason, and not just the easy option? I do not know the answer – but such questions need to be asked.”

Read more from The Spinoff: