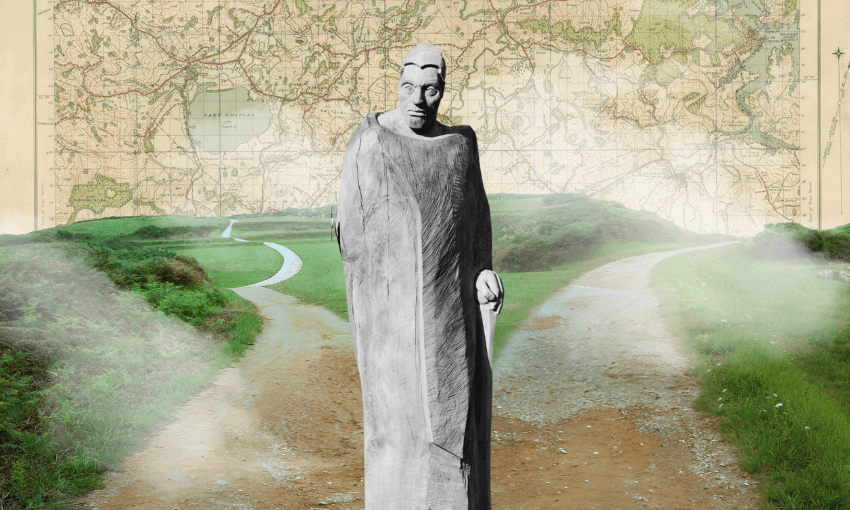

The largest iwi in Aotearoa has yet to settle its Treaty claim. As debate continues, Pene Dalton makes the case for clarity and courage. And settlement.

Ngāpuhi is the largest iwi in Aotearoa, with over 180,000 people connected by whakapapa – and our population is growing. That growth brings pride and potential, but also pressure – more mouths to feed, more rangatahi seeking opportunity, and more whānau navigating systems that have long failed them.

Many in our rohe live with the daily realities of poverty, addiction, poor housing and disconnection. Mane Tahere’s recent public plea to address the meth crisis wasn’t an exaggeration, it was a heartfelt call for help. It voiced what many already know, but don’t always say out loud: Ngāpuhi faces deep and complex challenges.

Some believe a Treaty settlement for Ngāpuhi will solve everything. It won’t, but it could help. A settlement would likely bring resources to support housing, education, language and land-based initiatives. Still, even if Ngāpuhi settled tomorrow, it would take decades to see the kind of results achieved by other iwi.

Tainui and Kāi Tahu, for example, have built economic platforms worth billions – but only after nearly 30 years of investment, leadership and learning from missteps. Ngāpuhi hasn’t even begun that journey in a unified way. We’re still debating how to get to the starting line.Some suggest a Ngāpuhi settlement might be worth around $500m. It’s not an official figure, just an estimate. Many argue it’s far too low, pointing to bailouts like the $1.6bn for South Canterbury Finance. But the real question is: are we ready to receive and grow that pūtea?

The greatest challenge isn’t the dollar figure, it’s unity. Getting a mandate from all hapū within Ngāpuhi is incredibly difficult. Ngāpuhi is not one voice. Some want hapū-led negotiations, others support a unified iwi-wide approach. There are real concerns about losing mana motuhake and justified distrust of imposed structures.

There is a time to protest and hold the Crown accountable, but some of us have remained in that space too long. There’s also a time to negotiate. The table may be flawed, but we still need people who can sit at it with integrity, strategy, and a long-term view. That mahi will never please everyone, but it’s necessary.

Do we settle as one iwi or splinter into hapū-based settlements? If we settle, can we stay united enough to manage what comes next?

Some critics ask why Ngāpuhi doesn’t follow other indigenous models overseas. But no two treaties are the same. They were signed under different circumstances, with different governments, and different histories. While we may share similar values or trauma with other indigenous groups, that’s often where the similarities end.

Even among iwi here, comparisons can feel uncomfortable. Some say we shouldn’t compare ourselves to others – there’s truth in that. We need to carve our own course. But comparisons to iwi not far removed from us culturally or historically can offer insight. If others have taken 30 years to build their base, we should be honest about the road ahead for us.

We also need to be strategic. If we’re holding out for legal recourse instead of settlement, what would that actually involve? What would it cost and where would that money come from? These questions deserve serious discussion, not just slogans.Personally, I support settlement – not because it’s perfect and not because I think it will solve everything – but because I want to see pūtea flowing into kaupapa that are already making a difference. For me, it’s about starting to rebuild, not waiting for ever for the perfect solution.

There’s another hard truth: many of us are still hoping for recognition without realising that political leverage matters. If we aren’t voting, or voting strategically, why would those in power listen? Until we can influence the makeup of a government, we’re relying on goodwill. That’s not enough.

Some argue settlement is a sellout. That money is the root of all evil. That engaging in this process means giving up our mana. I’ve heard it many times, but I disagree.

Our tūpuna weren’t afraid of money. They weren’t afraid of trade, negotiation or enterprise. Even before coin and currency, Māori had an economy. We bartered across the motu. Pounamu, kai, textiles, tools, knowledge. We understood value. We had systems grounded in reciprocity, mana and trust. Ngāpuhi sent produce across the sea to Port Jackson, Sydney. We traded with whalers, missionaries, merchants. We adapted and we built.

Some prefer the term “restitution” over “settlement”, I understand that. But my impatience to see tangible change – to see investment in the initiatives already doing the mahi – makes that debate feel more about language than impact.

Money is not foreign to our tikanga – it’s a tool. If we want to restore our people, our land, our reo, our oranga, we need resources. That’s not assimilation, it’s tino rangatiratanga.

Many Māori who were raised in cities are returning home – descendants of those who left in search of work. Some were raised disconnected from Ngāpuhi identity, reo and tikanga. Their return has brought energy, ideas, and sometimes tension. These shifts have reshaped parts of the rohe – for better and for worse – but this too is part of our evolving story.

If you carry Ngāpuhi whakapapa, you have a right to care and a right to speak. Whether you’re in Kaikohe, Tāmaki, Perth, or Nagasaki, Japan. Ngāpuhi are some of the most opinionated people you’ll ever meet – and that’s not a weakness – its a sign of life, pride and connection.

We won’t all agree – we never have – but we all have a stake in where we’re headed. Settlement is not the destination, it’s just the beginning. We owe it to our kaumātua who’ve carried this burden for decades and our tamariki and mokopuna who will carry it forward. Most of all, we owe it to ourselves to step up with courage, clarity and purpose.

Now is the time.