Lorde has couched statements about her gender cautiously, but they’re still welcome and radical for women who grew up thinking traditionally masculine traits were a flaw.

The first time I realised I could choose to buy men’s clothing was in April 2023.

I’d worn “old man pants” in the 90s (previous owner likely deceased) during a brief flirtation with grunge dressing, but that wasn’t a conscious choice; it was the result of cultural instruction.

Aged 43, I stood behind a curtain in a dressing room in the menswear section of 2nd Street, one of several vintage clothing stores in Hiroshima’s Hondori shopping district, and pulled on a pair of Homme Plissé Issey Miyake pants. They were black, famously pleated and to the naked eye, had nothing to suggest they weren’t the same as the black, famously pleated women’s version of the pants. Only the label and the gaping at the crotch, fastened by two buttons, gave the game away.

I’d landed in the menswear section after encountering a common problem for anyone of antipodean proportions. Japan is a mecca for vintage and preloved designer shopping, but it primarily caters for a domestic and smaller-sized market.

Disavowed of the savvy and strictures of familiar culture and humbled by a lack of language, I had tentatively wandered up to the menswear section after realising nothing in the womenswear would fit. I took baby steps, grabbing a scarf that fit my restrictive idea of what was acceptably “unisex”. Realising no one but me cared who I was or where I was, I moved towards items that, through cut, sizing, areas of coverage and decades of cultural conditioning, were more denotatively male: trousers, jeans, shirts, jackets and shoes. I left Japan with more menswear than womenswear. I haven’t stopped browsing and shopping on both sides of the strangely upheld border between the two since, but it took a long time getting there.

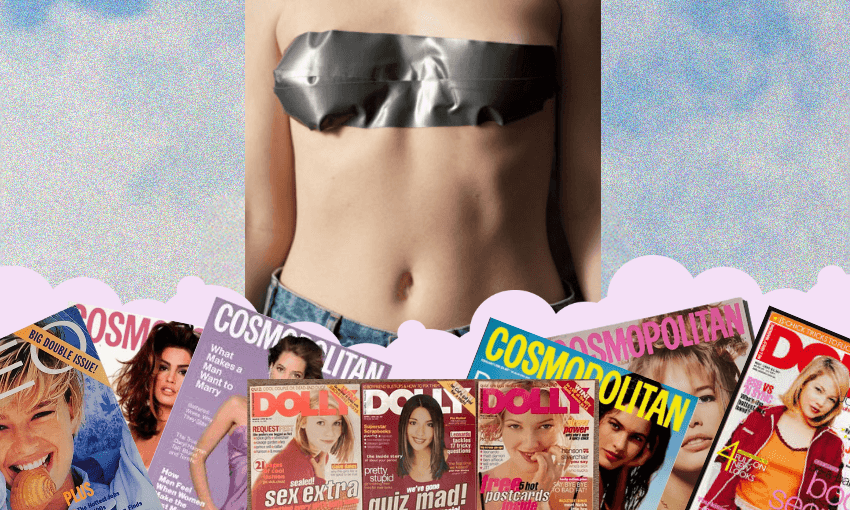

Growing up in the analogue 90s, before iPhones, social media, the mass adoption of the internet and the infinite splintering of cultural understanding, Western ideas of femininity were shaped by Hollywood and women’s magazines. Despite Mum’s best efforts to guide me away from these bibles, issues of Cosmo and Dolly (stolen from the public library) informed my friends and me about beauty, sex, sexuality and what it meant to be, and look like, a woman. It was a strange and contradictory time for feminism. The Girls Can Do Anything poster, on display in classrooms throughout the country in the 1980s, presented a wholesome ideal of women doing “men’s jobs” like welding and lifting heavy things. The 1990s were informed by a highly sexualised explosion of “girl power” and corporate “have it all” culture. It felt progressive, but at the zenith of mass and monocultural media, it was informed by singular ideas of desirability, identity and appearance. Xena, Warrior Princess (Lucy Lawless), now regarded as a canonical lesbian icon, appeared on the covers of Maxim and Stuff For Men – men’s magazines in the tradition of FHM and Loaded – wearing her underwear. “Xena as you’ve never seen her before.”

As a teenager, and every day since, I have never once looked in the mirror and seen what I’d describe as a typically feminine face. I once took a celebrity look-alike quiz online and got Russell Crowe. My face, to be clear, is fine, and I have no doubt people looking at it might dispute what I just said. For me, though, I had a list of defects that took away from what I understood as “pretty” and, therefore, what women should look like. My eyes were too round, and not almond-shaped or wide enough. My mouth was too small. My hair was never long enough, and my chin was too pointy. The most egregious was a lack of sharp cheekbones. “I have no cheekbones,” I would wail, ignoring the obvious lack of complete facial collapse that would occur if that were true. I resigned myself to a simplistic binary: not “pretty” meant masculine, and that wasn’t something to embrace or even accept as OK.

I vividly recall being described as “handsome” by someone in passing and wanting to die. While I now share the view expressed by Tilda Swinton about her father and David Bowie in 2011, it got under my thin and stubbornly dull skin at the time. For a man, “handsome” is good, but for a young woman with no reference points for embracing any kind of fluidity or positive connotations about masculinity as a woman, it was antithetical.

I also absorbed ideas that being articulate, smart, “intimidating”, and a leader were masculine qualities, which were at war with the feminist ideals I was rapidly absorbing at university. To me, the pathway to being a fully-rounded woman was to wrestle those ideas to the ground, bludgeon them to death and reabsorb those “masculine” characteristics as feminine. There was never any contemplation that a reconciliation could occur between the different parts of me, or that embracing masculinity as an act of positivity was an alternative.

Through my 20s and 30s, I was very overweight. Year after year, the pages of my university diaries were a testament to the era’s contradictions. Bullet-pointed goals included: “finish Masters” (I did not) and “lose 10kg” (also not achieved).

I’d also discovered an admiration for masculine tailoring and androgynous fashion. Studying film, I spent hours falling in love with Katharine Hepburn’s screen presence and her trousers. I watched Annie Hall and wanted nothing more than to sling a tie around my neck. By the time Sally Potter’s adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando arrived on my required screening list, I was completely besotted with the interplay between trickery, freedom, identity, gender and style.

There’s a particular cruelty in wanting to dress more androgynously when you already feel like your body occupies too much space and isn’t conforming to a desired ideal. Choosing clothes that made me look “bigger” felt like a form of self-sabotage, and clothes that weren’t “feminine” just highlighted broad shoulders and a wide back. Despite a growing mental catalogue of masculine sartorial icons, “flattering” was the only style preoccupation I allowed myself to have. There was nothing more humiliating to me than having people think I didn’t understand my own body or the rules that should apply.

I did eventually lose weight via gastric bypass surgery. I’ve reconciled how that changed my relationship with my body privately and publicly. It also changed my style. I rarely wear dresses and frequently wear men’s jeans, shirts and jackets. Driving through the heart of Auckland’s University Central City campus one day wearing sneakers, men’s jeans and a sweatshirt, I realised that aside from shape, there was no real difference from behind between me and the 20-something-year-old men mooching along Princes Street.

The reasons for this late-stage and, by the standards of more enlightened generations, quaint transitory phase are ripe for an unfurling of caveats, discursive criticisms of just about every aspect of life today, and self-flagellation, but the most permissive and accurate description I have found is clunky and base. It’s not my description but Ella Yelich-O’Connor’s, and it’s held together by the completely obtuse and amorphous concept of “the ooze”.

Two weeks before Lorde’s single “Man of the Year” landed, her interview with Rolling Stone was published. In it, she details how she came to a different understanding of gender. It’s layered and authentically rooted in her own experience. She talks about an eating disorder, growing up famous, a break-up, therapy, anxiety and the relentless drain of existing in the limbo of being what people expect you to be and being yourself. She describes buying men’s jeans, taping her chest and feeling like a man on some days, and a woman on others. The ooze is defined as “the act of letting herself take up more space in everything she does, whether physically or creatively. Doing so opened the floodgates of her own identity”.

“My gender got way more expansive when I gave my body more room,” she explains. She is careful not to overegg this disclosure, saying, “I don’t think that [my identity] is radical, to be honest,” she says. “I see these incredibly brave young people, and it’s complicated. Making the expression privately is one thing, but I want to make very clear that I’m not trying to take any space from anyone who has more on the line than me. Because I’m, comparatively, in a very safe place as a wealthy, cis, white woman.”

And she is. Despite her assertion that her gender expression isn’t that radical, conversations about gender have simultaneously become more nuanced and visible, and contentious and dangerous enough to be ascribed the language and conditions of warfare. The war is cultural and ideological, but protests, abuse, violence and death are now its regular companions for those without the safety of Lorde’s position. “Woke Lorde accused of ‘gender baiting’ as she appears to come out as non-binary… but there’s a twist,” screamed The Daily Mail, a publication that lives and dies by the potency and twisting of bait.

I also write from a position of safety. I am a cis woman, and all I’m doing is wearing men’s clothing. I wear makeup, dye my hair and sometimes remove my body hair. I’m not existing in a particularly unacceptable, challenging or radical way. When I put on those pants in Hiroshima, I wasn’t challenging much at all, except my own restrictions. It was still a revelation.

Revelations always seem like they’re meant to be sudden. This one crept up over decades. Maybe that’s what Lorde means by “the ooze”. It’s the slow acknowledgment that you’re allowed to take up the space you actually occupy. Growing up on a diet of highly prescribed ideas of femininity, it’s taken time to peacefully inhabit that space and not see traits traditionally ascribed to masculinity as a flaw. Nothing needs to be bludgeoned to death and absorbed to fit one of the binaries. It’s expansive. Sometimes, to become someone more like yourself, you’ve just got to wear the pants.